Ron Howard Takes a Look Back on 'American Graffiti' 50 Years Later

Ron Howard didn’t have high hopes for what would become the most formative—and transformative—moviemaking experience of his young life.

“I think we felt like it was a good, low-budget, kind-of-indie job,” says the acclaimed actor-turned-director, speaking with Parade about making American Graffiti, which will mark its 50th anniversary this summer. “I don’t think any of us thought it was destined to be a hit. I thought it would probably play drive-ins on the summer circuit, like any other teen movie.”

Of course, American Graffiti became much more than “any other” teen movie.

Debuting in a single theater in Los Angeles on Aug. 12, 1973, it quickly mushroomed into a massive, crowd-pleasing pop-cultural phenomenon. A hit in theaters everywhere, it was later recognized as one of Hollywood’s first “tentpole” movies, a film so over-the-top successful at the box office that it could support, and mitigate, a studio’s less-profitable releases. It’s now regarded and revered as a rule-breaking cinematic triumph, a potent launching pad for several Hollywood careers and a timeless coming-of-age, California car-culture classic. The American Film Institute lists it on its registry of the 100 greatest films of all time, and it’s preserved in the National Film Registry and the Library of Congress.

Howard, now 69, recalls seeing the finished movie in Los Angeles shortly after it opened. (He went with his girlfriend, Cheryl, who’d become his wife in 1975.) “It was amazing,” he says. “Like a rock concert—people were clapping as soon as ‘Rock Around the Clock’ [the song that sets the opening scene] came on. And laughing—huge laughs. I had no idea how funny it would play to an audience. A couple of weeks into release, it had already taken on a kind of cult status.”

Getty Images

Cars & All-Stars

Set in 1962, American Graffiti takes place during one eventful evening in which the characters embark on various nocturnal adventures and escapades—kids flirt, cars prowl and growl along city streets, and everything builds to a climactic drag race (and no, not the RuPaul kind) on the edge of town.

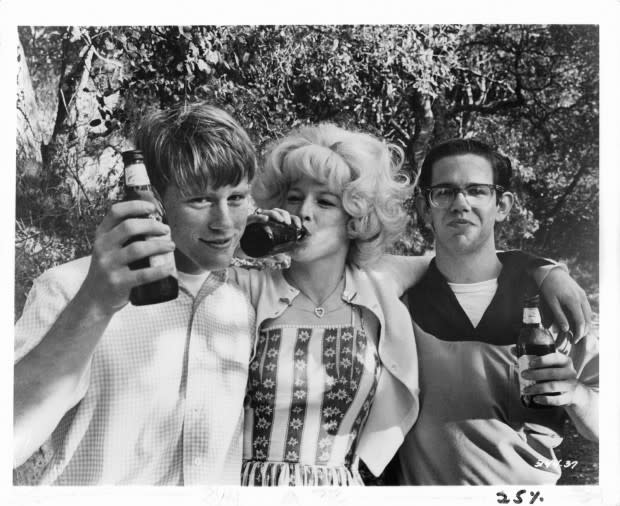

Howard was part of an all-star ensemble as Steve, a straight-as-an-arrow, recently graduated senior class president eager to embrace life after high school—which isn’t exactly what his head-cheerleader sweetie (Cindy Williams) has in mind. Curt (Richard Dreyfuss) is a college-bound loner searching for the beautiful mystery blonde (Suzanne Somers) who catches his eye from another car before driving off into the night. A nerdy doofus, Terry the “Toad” (Charles Martin Smith), puffs up his bravado to impress the spunky Debbie (Candy Clark). A plucky young girl (Mackenzie Phillips) takes a wild spin with a hunky hot-rodder (Paul Le Mat), whose title as the town’s top street-racer is challenged by a trash-talking interloper (Harrison Ford).

Related: From Indy to Han Solo, We've Picked 15 of Harrison Ford's Best Movie Roles

And through it all, a radio DJ (Wolfman Jack) keeps the hits coming on the radio.

“To watch American Graffiti now is such a fun experience,” says Turner Classic Movies host Dave Karger. “It’s the perfect combination of memorable characters and the perfect actors to play them. It’s very exciting to witness those future megastars at the beginnings of their careers.”

The director of the film, George Lucas, was also at the beginning of his career. He’d already made his debut with a small independent avant-garde sci-fi film, THX 1138, a box-office flop. But he’d go on, a few years later, to create one of the most iconic blockbusters of all time, Star Wars, kicking off an ever-spawning franchise.

When Howard was 18 and began shooting American Graffiti, he was already a Hollywood veteran. He’d been working in TV since he was a toddler and was known in living rooms everywhere as Opie on The Andy Griffith Show, a role he played for eight years beginning when he was 6.

But even with a substantial amount of acting experience under his belt, he felt like somewhat of a greenhorn coming into American Graffiti, set at a time when he was a still a preteen. “Those cars, those songs, [they] felt ancient to me as an 18-year-old,” he says. I didn’t know some of the expressions, some of the hot-rod lingo. I didn’t know anything about Wolfman Jack. I didn’t know most of the music that was going to be in the soundtrack.”

But he knew that American Graffiti came along at a good time, a transition point in his career where he was trying to evolve from stereotyping as a child actor to more substantive, grown-up roles.

“I had no idea of what the reality of that would be,” he says. “But being a part of American Graffiti was kind of a declaration for me—that I could ‘graduate,’ I could transition beyond The Andy Griffith Show to, at least, a young-adult level.”

Getty Images

Opie’s Shadow

Howard, unlike most of the characters depicted in the movie, was never a car buff or a tire-squealing cruiser. He drove his decidedly non-rod 1970 VW Beetle to the movie set, where filming began in Modesto, Calif., (Lucas’ hometown) before relocating to nearby Petaluma. And he found out that Opie, a role he had played across some 240 TV episodes, cast a long shadow beyond the TV town of Mayberry.

“One day, Paul Le Mat and Harrison Ford were on our day off, having some beers and getting loose, cracking jokes,” Howard says. “And they started pitching these beer bottles [off the motel balcony] into the parking lot, kind of like they were rock-and-roll [stars] or something.” And those lobbed beer bottles were landing, and shattering, dangerously close to Howard’s dependable little VW Bug.

“I said, ‘Guys, I don’t want to disrupt your fun, but give me a minute and I’ll go out and move my car, OK?’ And they said, ‘Sure.’

“So, I go down and I’m headed toward my car and, all of a sudden, a beer bottle lands, like, 10 feet from me. And they were going, ‘Dance, Opie, dance!’ and firing these bottles as I was running over to get my car.” He laughs. “No injuries, but kind of fitting for their characters as the movie’s ‘bad’ boys.”

The movie is a Hollywood marvel in that so many of its actors—bad boys, good girls and everything in between—went on to bigger things. Howard appeared in other films and a hit TV series (Happy Days) before switching to make movies on the other side of the camera as a director. One of them, A Beautiful Mind (2002), brought him a pair of Oscars, while others—genre-spanning comedies and dramas including Splash, Cocoon, Parenthood, Backdraft and Apollo 13—became pop-cultural touchstones.

On this summer afternoon, he’s in the Los Angeles offices of Imagine Entertainment, the production company he founded in 1985 with producing partner Brian Grazer. As he talks, his eyes fall on a particular memento, a framed photo from a reunion of the American Graffiti cast, taken some 25 years ago.

And for a moment, it makes him wistful.

“It’s reminding me of Cindy,” he says, referring to co-star Cindy Williams, who died in January of this year at the age of 75, after a brief illness. “It’s still pretty heartbreaking, and fresh on my mind.”

Howard and Williams played young lovebirds in Graffiti, then went on to appear together in Happy Days. They reprised their Graffiti roles in the film’s 1979 sequel and appeared together in additional projects, including a TV movie, The Migrants, based on a play by Tennessee Williams, and a ribald film comedy, The First Nudie Musical. Howard guest-starred in two episodes of Williams’ own Happy Days spinoff, the breakout TV comedy series Laverne & Shirley (she was Shirley), in 1976 and 1979.

“Man, we sure had a period of time where we were acting partners, it seemed more often than not,” he says. “I saw her last year, and she looked great. She was still laughing and lighting up the room with all her positivity and her sense of humor. Anyway, yeah, I miss her.”

As their first acting project together heads into its milestone 50th anniversary, Howard clearly enjoys the recollections of working with Williams and the other actors, under the tutelage of an ambitious, pioneering young director who pushed everyone to make the film on a grueling shooting schedule and a shoestring budget of considerably less than a million dollars.

Getty Images

Long Nights, Tight Budget

“George shot in sequence,” Howard says, referring to filming scenes in the order they would naturally occur in the story. “He knew that with all of us staying up all night for five or six weeks, we’d look exhausted at the end,” just like their characters—rumpled, strained and drained. “By the time he was filming the final scene, man, we were exhausted. All that wear and tear, those circles under the eyes, that was from weeks of continuous, all-night shooting.”

The budget was so tight, the actors—male and female—shared a single on-set trailer, a Winnebago. “We got pretty cozy, seeing everyone in their underwear half the time,” Candy Clark recalls in a making-of documentary for the movie’s DVD rerelease in 1998. There was no makeup artist—because there was no makeup, other than what the female actors self-applied. “Just as they would if they were going out for a night of cruising,” says Howard.

“We didn’t have any creature comforts,” Charles Martin Smith notes in the documentary. “There were no chairs on the set. We had to sit on curbs, or in a car.”

In the years to come, Graffiti would be widely praised for its innovations, particularly how it made low-light night scenes (notoriously difficult for moviemaking) look natural and realistic; actors were encouraged to veer off-script and improvise; and the lean production was a case study of how to make the most of extremely limited resources.

“The detail that was captured, the nuances of the performances, the feel of the setting—all achieved very economically, very efficiently,” says Howard.

And the music, music, music! Lucas had specific songs in mind to go with virtually every movie moment and all the scenes, which were written to go with the music he preselected using his sister’s record player and a stack of 45s. And rather than just a here-and-there sonic backdrop, as in most films, the music was almost an unseen character, a sock-hoppin’, teeny-boppin’ presence from start to finish, providing a nearly constant, continuous serenade as the p.m. gave way to the a.m.

“The music was the forefront of the characters, the setting, the plot,” says TCM’s Karger. “It really drives the movie. That’s one of the things that makes it so special, so groundbreaking.”

It was groundbreaking too, says Howard, in how American Graffiti showed that the right combination of elements—story, talent, craft and innovation—could turn a teen-romp “hangout” comedy into a movie masterpiece, one now being discussed 50 years later. “Every time I watch it, or even a few minutes of it, I’m very proud of it,” Howard says. “It really holds up.”

It’s a “teen movie,” yes, about kids and cars and cruising dusk-to-dawn. But there’s something else. “It’s about a loss of innocence and a cultural transition,” says Howard. “What it means to grow up.” Director Lucas has said he wanted to underpin the vignettes of the characters with a subtext about changes in America in the early 1960s, when the country itself was transitioning into a new, uncertain era—the beginning of a war in Southeast Asia, the unrest of the civil rights movement, a “British invasion” of the pop charts. “Life passages centering around the idea of change,” Lucas says. “You go from being a student into the real world, you leave your hometown, you leave your family. Parallel that with what was going on in America at the time.”

Related: These Are the 60 Best High School Movies of All Time

The movie’s postscript, revealing what happened after the events of the film, is a somber note about those very kinds of passages and change. We learn that one character has died, and another is missing in action in Vietnam, and yet another has left the country to live in Canada—as many young men did, at the time, to avoid the draft. “I think that gave the movie a lot of gravitas, and surprised people at the end,” says Howard.

And it all reminds him how he was still a teenager—like his character in American Graffiti—when he made the movie, an 18-year-old confronting change of his own, charting his movie career thinking about one day becoming a filmmaker himself.

“It basically catapulted me into adulthood,” he says. “It was so significant, a huge confidence builder. At this stage of my life, it makes me happy to look back. It definitely makes me smile.”