The Story of Heady Topper, America's Obsession-Driving Double IPA

? Corey Hendrickson

This story was co-funded and co-produced with our friends at Longreads.

For eight years, until Tropical Storm Irene struck the village of Waterbury, Vermont, the corner of South Main Street and Elm was occupied by The Alchemist Pub and Brewery. It was, by most measures, a common small-town bar. The walls were chocolate brown brick. The barstools were steel and backless and topped with black leather. A pool table sat in the corner. The ceilings were high, and the lighting was soft. A cast of regulars helped fill the pub's 60 seats. It was charming in its familiarity, quaint and comfortable, but brewing in the basement was a beer capable of inspiring obsession. It was called Heady Topper and since the pub was the only place you could buy it, Waterbury—home to just a few thousand—soon became a mecca for craft beer drinkers.

The pub belonged to Jen and John Kimmich. Jen ran the business side, and John handled the beer. They first met in 1995, when they were both working at the Vermont Pub and Brewery in Burlington. John had made his way there from Pittsburgh. He'd been enthralled by a home brewer and writer named Greg Noonan who was a pioneer in craft brewing, especially in New England, where he helped push through legislation that recognized the concept of brewpubs.

After graduating from Penn State, John packed everything he owned into his Subaru and drove to Vermont in the hopes that Noonan would give him a job. He did, and for a year John waited tables, coming in on the weekends for no pay to learn the trade alongside the head brewer. Then John became the head brewer. Jen was a waitress at the pub. After turning down John's initial first-date offer, she came back a week later and asked him out. A month later they were engaged.

Two months after the Kimmiches opened The Alchemist in Waterbury, John, driven by an obsession with fresh, floral, hoppy flavors, brewed the first batch of Heady Topper. The immediate response from customers upon tasting it was bewilderment, followed by intrigue. Their eyes scanned the room, meeting all the other eyes scanning the room, all of them in search of an answer to the same question: What is this? "People were shocked, maybe," John says. "They would taste it and go, 'Oh, my god.' They'd never had anything like that before. People really went nuts for it."

At first, John didn't brew Heady year-round. He would make it two times a year, then three, then four, tinkering with the recipe each time. He had other beers to make, like Pappy's Porter or Piston Bitter or Bolton Brown. They were all distinct, unusually compelling beers, but soon word began to spread about Heady: It was a hit. The problem, if there was one, was that it was only available in the pub. Enterprising customers solved it by sneaking pints into the bathroom, where they would pour them into bottles, screw on caps, and then shuffle out of the bar, pockets bulging. The business and the Alchemist name were growing with rapid, radical speed, beyond anything the Kimmiches had anticipated—and then the storm came.

Irene arrived in Vermont on a Sunday afternoon in August 2011. It roared north from the southern end of the state. Waterbury's usually calm and placid Winooski River, a short distance from the pub, swelled uncontrollably. The local waterways and tributaries overflowed, and the contaminated water rushed through town, absorbing sewage and sodden trash and heating oil, staining everything it touched. Trees and shrubs were unearthed or turned gray and brown, like they'd been doused by a plume of ash. Cars were flipped; bridges buckled and collapsed; houses were left twisted and roofless. In some stretches of the state, more than a foot of water fell.

From their home in Stowe, just 10 miles north of Waterbury, Jen and John and their son, Charlie, watched the storm unfold. When they got the call that Waterbury was being evacuated, John jumped in the car and drove down, powerless but determined to see the destruction with his own eyes.

By the time he arrived at the brewpub, the basement—where he had been brewing for eight years, where he stored the original recipes for more than 70 beers, and where he and Jen had their offices and kept the food—was completely under water. On the first floor, John stepped inside. The water was not yet waist high, but it was well on its way, so he worked his way to the bar and poured himself a final pint of Holy Cow IPA. Then, with the water rising at his feet, he raised his glass skyward and toasted goodbye to everything they'd built.

***

? Corey Hendrickson

For the better part of the last three decades, America's best-selling style of craft beer was pale ale. In 2011, it lost that title to India pale ale, a style often defined by higher alcohol and more prominent hop flavors. Heady Topper is a double IPA, which means it's one more notch boozier and hoppier. It is fruity and frothy and hazy gold. John describes it as "a beautiful tribute to dank American hops." And now, in New England, it's the standard.

"2011 was a watershed moment," says Jeff Alworth, author of The Beer Bible. "America was finding its palate. When you look around the world, wherever there's a native beer, you always see people develop their own interests and passions about certain kinds of beers." Think Bavarian lagers, or British cask-conditioned ales, or Irish stouts. In America, the IPA is king.

About five years before IPAs began to climb the bestseller lists, there was a widespread shift in their brewing process, says Alworth. Many brewers began to focus on a technique called dry hopping, which calls for adding hops to the beer after the boil, when their nuanced flavors and aromas won't be cooked away. There was also a rise in the use of aroma hops, like Centennial, Cascade, Mosaic and El Dorado, that introduced an entirely new flavor profile to IPAs. This resulted in "a massive balm of vivid flavors and aromas without a ton of hop bitterness," says Alworth. "And I think that's something that Heady brought a lot of people to."

Heady tends to surprise people who associate big, hoppy beers with bitterness. "It's got this tropical fruit flavor, and it's super-, super-balanced," says Ethan Fixell, a beer writer and Certified Cicerone. "I think there's a crossover appeal that's really key to its success. My friend's 75-year-old dad had never drunk an IPA in his life. Then he tried Heady, and now he's obsessed with it."

Alworth doesn't believe the IPA, America's most popular craft beer, will be ousted anytime soon. That would demand a massive shift in taste. It's like cuisine, he says, and when you develop an approach, you stay within range of familiar flavors and techniques. "If you're in France, you're not making food like they do in Peru or Thailand," he says. "That's how beer tends to go. And it seems to me that the American palate is totally focused on these expressive hops that we grow here."

***

Two days after the flood, and just a few minutes up the road from the felled brewpub, the first cans of Heady Topper rolled off a production line. Jen had convinced John, over the course of a few years, that opening a cannery was the next logical step for The Alchemist. "Jen was absolutely the driving force behind it," says John. "I really wanted nothing to do with it because we were so busy at the pub. She had the foresight to say, 'No, we need to do this.'" In the aftermath of Irene, what Jen had initially conceived of as a push forward for the business was now all they had left.

"People were coming over and buying Heady, and we knew we were at least helping a little bit," John says. "Those were an emotional couple of days. It was wild."

"We were able to bump up production there immediately and employ some people from the pub," Jen says. "That was really important to us."

The new cannery had a small retail space and tasting room. Now, for the first time, Heady Topper—the elusive beer that had sprung from word-of-mouth sensation to being the talk of internet forums and message boards, to eventually being ranked the number one beer in the world on Beer Advocate, a popular beer-review website—was available to go.

? Corey Hendrickson

In the cannery's first year, production of Alchemist beers increased from 400 barrels (the amount John had been brewing at the pub) to 1,500 of Heady Topper alone. A year later, they were brewing 9,000 barrels of the double IPA. But that still wasn't enough to satisfy demand. Soon after opening the cannery, John and Jen had to limit the daily number of four-packs they could sell each customer or they wouldn't have enough to stock the retailers, mostly small mom and pop shops, around Waterbury. Some customers got around this restriction by keeping wigs and changes of clothes in their cars so they could return for a second allotment. "At that point," Jen laughs, "we don't try and police it."

Heady's fame provoked more audacious feats as well. Beer tourists drove hundreds of miles into town. Beer-loving newlyweds chose Waterbury as a honeymoon destination. One family flew in on a private jet from South Africa, grabbed their daily limit and then returned home.

The parking lot was consistently full, and traffic began to spill onto the roadside. Cars backed up to Route 100 and began interrupting its flow. Soon, neighbors complained. Eventually, so did the state. Two years after opening the brewery, the Kimmiches had no choice but to close their retail store. As a result, buying Heady became a sport; if you were willing to learn delivery schedules and wait for trucks to pull up outside general stores and gas stations, you might score.

In July 2016, The Alchemist opened a second brewery location in Stowe, this time with the fans in mind. It's a football field of a building, 16,000 square feet, with an extra-large parking lot and sprawling windows framing mountain views. The facility brews an IPA called Focal Banger and a rotating lineup of other beers, but Heady is for sale here. Customers line up like they're waiting for a roller coaster, then churn through the space, grabbing four-packs, T-shirts, hats and posters emblazoned with the Heady Topper logo and the tagline "Ready for a Heady?"

***

? Corey Hendrickson

In 2012, Ethan Fixell drove from New York to Vermont. After coming up short at six stops, he was overheard pleading his case at one shop by a local who instructed him to head to a deli about 15 miles away. Fixell made off with 16 cans, the most the deli would sell him, and then he took a hike.

"It was summer in Vermont, and I'm walking in the forest, drinking Heady out of a can, and I was like, 'Man, this is the best beer I've ever had in my life,'" he says. "That's like everyone's experience. People talk about the beer like it's got fucking unicorns in it."

This mythologizing annoys John to no end. "This isn't some magic formula," he says, though Heady's exact composition is of course a secret. John will reveal that Heady is made with British barley and American hops, and that the beer is a tribute to the hop variety Simcoe in particular. Simcoe hops, developed and patented by Yakima Chief Ranch in Washington state, have been on the market only since 2000. The Alchemist's yeast, a key contributor to its beers' flavors, was a gift from John's brewing mentor, Greg Noonan, who obtained it on a trip to England in the 1980s. The only condition: John could never share the original culture with anyone else.

Despite John's assertion that Heady Topper isn't special, it is still his baby, still his favorite beer to drink—and he has rules for its consumption. Mainly, he insists that it be drunk directly from the can. When Heady is poured into a glass it immediately begins to die, he says. "All that carbonation is coming out, the CO2 is escaping, the aroma, the hop essence, and oils. When you drink it out of the can, the beer is perfectly preserved. There's a layer of CO2 riding through that can, and when you pour the beer into an empty glass, you're immediately accelerating the expulsion of all that goodness." Other brewers are skeptical of this, but John is insistent.

John also holds that Heady should be kept cold at all times, and he has said he can tell when a can has warmed up and chilled back down. Not every Heady devotee buys this, but few want to take a chance. An employee at Stowe's local hardware store, a short distance from the brewery, says his cooler sales have soared since The Alchemist opened the second facility. Selling particularly well is a heavy-duty model that can keep ice frozen for up to a week. That one isn't cheap, though. "People have to weigh it out," he says. "They say, 'If I buy one of these, I can't buy as much Heady.'"

John is quick to dismiss any talk of Heady pioneering a new style, or even the existence of a Vermont-style IPA. "What we do," he says, "doesn't deserve its own category."

Jeff Alworth has a different opinion. He draws a line between Heady and Pilsner Urquell, which was first brewed in 1842 and still largely follows the same recipe. "If you can do a founding beer like this, one that defines a style, it will last and carry a brewery on for decades or even centuries and continue to be really well regarded," he says.

"I don't think any Americans think in those terms," Alworth continues. "They don't think, I'm developing a beer that will be here 100 years from now, and the beer geeks, riding around in their space packs, will be praising this beer and consider it the hallmark of the style. But that could happen. Heady could become that beer."

***

? Corey Hendrickson

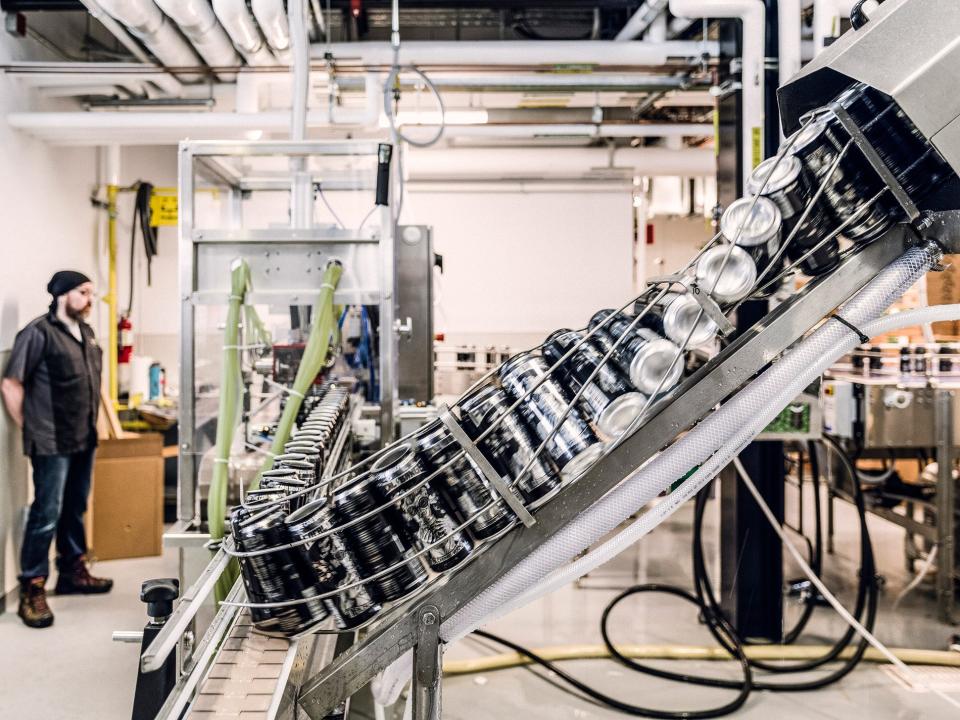

It's just after eight in the morning, and the canning line is firing at full speed inside the brewery in Stowe. It's a cacophony of machinery, all whirs and clicks and hisses, and as the cans move down the line and approach finality, one veers off course, causing a pyramidal buildup behind it.

"Can jam!"

A few feet from the scene, Kenny Gardner, a canning operator who has been methodically plucking cans free to weigh them, making sure they equal 16 ounces (or one American pint), moves into action. He hustles over and guides the cans with his hands to return them to the proper position, using his forearms like bumper lanes. Then he exchanges a nod with a co-worker, indicating that order has been restored.

More than 30,000 cans of Focal Banger will be filled today, and these sorts of hiccups are regular, but it's a different role for Gardner, who began working for The Alchemist in 2004, at the brewpub. Eventually, he became head bartender, a job he enjoyed, but he likes this one, too. "I never thought I'd be operating a canning line, but it's been great," he shouts above the din. "Everyone's gotta work, so you might as well enjoy it."

Between the two operations, in Stowe and Waterbury, the Kimmiches now employ 48 people, in positions that don't immediately scan as normal brewery jobs. They have a videographer, for instance, and a wellness instructor. Many of the employees remain from the original brewpub days. Hostesses became distribution managers; bartenders became canning operators; waitresses became designers. Employees get full health insurance, retirement plans, paid sick days, paid vacation and subsidized child care.

? Corey Hendrickson

A few feet from Gardner, in the retail space, which is still hours from opening, other staff members are splayed out on yoga mats, having just completed their morning workout. Each day, The Alchemist shift begins with an optional fitness session, employees given the time and space needed to exercise.

This all factors into the beer, according to John. "The way we treat our employees, the atmosphere that we create, is the energy of The Alchemist, and we translate that into our beer," he says. "If this atmosphere was full of anxiety and anger and dissatisfaction, our beer would reflect that. There is a symbiotic relationship between the people working with that yeast to create the beer and the finished product. Our beer is alive."

John is the youngest of six children, and this past June, his oldest brother, Ron, moved from their home city of Pittsburgh and started working at the brewery. For decades before, Ron worked in corporate sales. John had talked to him in the past about making the move, but the timing was never quite right. When he finally took the plunge, his health was beginning to suffer.

"He had been treated for hypertension and a malfunctioning valve in his heart, he had high blood pressure. He was going to be on medicine for all kinds of stuff," John says. "After coming here, he lost 17 pounds. His heart valve is no longer malfunctioning, his blood pressure is down and his cholesterol is down. It's the lifestyle change, eliminating that stress from his life. My son is 12, and all of our family—his cousins, everybody—is back in Pittsburgh, so now that he's got his uncle Ron here, it's really great."

? Corey Hendrickson

"The first time I came to Stowe and saw all of this, I had tears in my eyes," Ron says. "To see them doing this, it's almost overwhelming."

There are no plans, the Kimmiches say, to expand, merge with corporate investors or become a larger operation. The opportunity is there, and has been for years, but the Kimmiches aren't interested.

"It would ruin the beer," John says. "Anybody who would have had partners and corporate investors would have been making 100,000 barrels a year by now because they would have been like, 'Yeah, we got something good here, and we're going to exploit the shit out of it.' There are guys out there and that's their goal. That's not our goal. Our goal is not to retire on a mountain of money. Our goal is to create a sustainable example of what a business can be. You can be socially responsible and still make more money than you need."

John is also content with his beer being a regional specialty. "You can't go to your favorite sushi restaurant from San Francisco in Des Moines," he says. "You've got to be in San Francisco. You've got to go to New York City for that pizza you love so much. You don't get it every day of your life, and you shouldn't. You should anticipate it and go out of your way to get it, and when you do it's great, but you don't get it again until you get it again, you know?"

***

? Corey Hendrickson

In the days following Tropical Storm Irene, the front lawns in Waterbury became littered with scrap wood and cracked siding and busted pipes ripped from rotted basements. Dumpsters overflowed with insulation, waterlogged couches and broken glass. The roads were still thick with mud, and the smell of polluted water still hung thick in the air.

The Alchemist Pub and Brewery was torn down to the floor joists and the wall studs. The Kimmiches began rebuilding it, but it never reopened. They decided instead to put their focus on the Waterbury brewery, and they sold the pub space to another brewer. Now, the corner of South Main Street and Elm belongs to Prohibition Pig. Inside, it is reminiscent of the original pub. The ceilings are still high, the crowds still lively, the taps still plentiful. Behind the bar, the bottles are stacked to the roof, and a ladder sits nearby, just in case someone needs to reach the top.On a Friday night in December, the inside of Prohibition Pig is bustling. In a far corner, a man in a suit printed with candy canes and snowmen lets out a guttural laugh. Nearby, a table of office workers clink glasses together. At the bar, two men in flannel shirts nurse pints. Outside, a group of people has gathered at the window to read the menu. Suddenly, someone shouts, "We got it!" The group turns to face two men rushing toward them, arms overflowing with cans of Heady Topper.

Their next decision is easy. Dinner can wait. After a brief chorus of hoots and hollers, they turn on their heels, steps from where it all began, and head into the night, arms now heavy with the beer that brought them here, but their steps long and light. Ready, at last, for a Heady.

Sam Riches is a writer and journalist based in Toronto.

Editor: Lawrence Marcus | Fact-checker: Matt Giles

This story was co-funded and co-produced with our friends at Longreads.