Teachers across America are talking about racial injustice with 'fed up' students: 'They're sick of living in a world that's trash'

Teachers across the country are having emotional, candid and sometimes imperfect conversations with their students about the death of George Floyd, racial inequity, police brutality and protests.

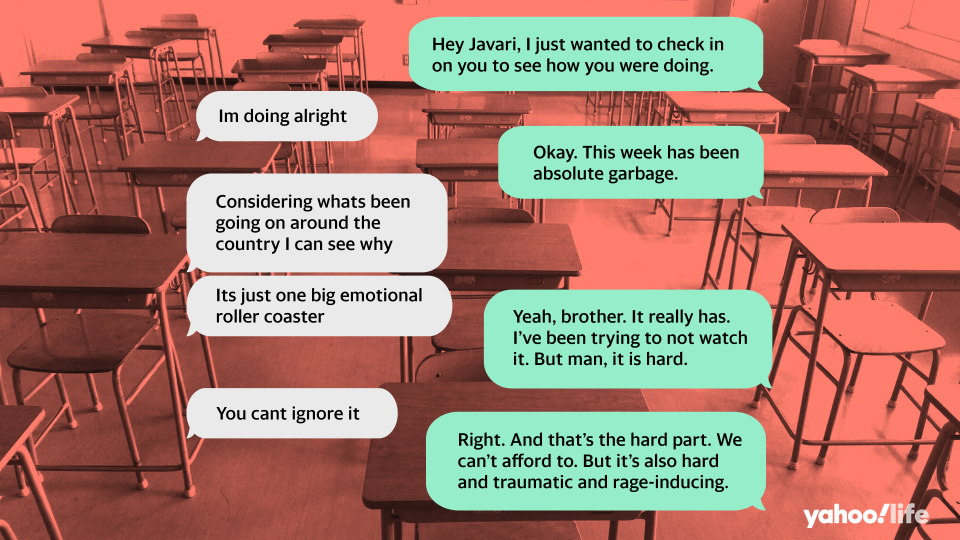

In Seattle, the first thing teacher Evin Shinn did when he heard about Floyd’s death was send a text out to all of his students.

“I said, ‘Hey, all, I just wanted to acknowledge the trash that is happening in our nation with regards to black lives. If we were in class, we’d debrief it and talk about it. It’s hard, real hard sometimes. If you want to chat, feel free to hit me up.”

In Chicago, Gregory Michie, a middle school social studies, language arts and media studies teacher at Seward Elementary, presented a series of slides to his students after Floyd’s death, reading the names and showing the faces of black lives taken at the hands of police brutality to help his students understand the anger behind the protests happening in their neighborhoods. “We also use the Martin Luther King Jr. quote about ‘a riot is the language of the unheard’ and had them think about what that means. So I think those things are helpful in putting it into a larger context.”

In New York City, Carlos Romero, principal at PS 126 Manhattan School of Technology, which teaches pre-K through eighth grade, says teachers, psychologists and counselors hold daily Zoom meetings with students to talk about the issues around Floyd’s death and to provide resources on how to take action against racial injustice. They also encourage the older kids to write their thoughts about the death of George Floyd in a blog. One student, Jared, wrote: “The media doesn’t seem to pay attention to protesters when it is done peacefully. They are now paying attention because their property is being damaged. It may be chaotic, but it is the only way for them to have change. At least that’s how protesters see it.”

“We talked a little bit about truly listening to the message and listening to the different perspectives,” says Romero. “And for them to be able to come up with their own perspective based on what they’re hearing.”

“How do you create a welcoming and safe environment? How do you deal with the anxiety that kids have? How do we make sure we meet their needs? How do we create more equity?’ says Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), which represents 1.7 million teachers across the county. “The dilemma is, this is not the first time we have focused on these issues, but it may be a tipping point in America that enables real change.”

The AFT, along with the National Education Association (NEA), issued a joint letter earlier this week supporting students across the country who are protesting police brutality and the death of George Floyd.

“How many times has a kid died at the hands of either a racist or police officers who are racist?” says Weingarten.

For Shinn, an 11th-grade U.S. history and language arts teacher at Cleveland High School in Seattle — a school with predominantly students of color— this was the first of a series of texts, letters and virtual meetups to engage his students about these issues.

“As a black educator, to quote [the movie] Network, ‘I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore,’” he says. “There’s so much rage. And so often in my classroom, I feel the need to temper that. I don’t want students to see that part of me, because I also want them to see that there are other ways to be angry.”

Shinn followed up with individual texts to his black students acknowledging that it’s a scary time, followed by a letter to all of the students and parents in his school.

“As a teacher, we don’t really know what to say. You don’t want to say everything’s going to be OK, because it’s not, right? We want to be honest and we want to be truthful to them about what’s actually happening.”

In his letter to students and parents, Shinn addressed the pain and rage he was feeling and acknowledged that a revolution is taking place. “I’m telling students to look around and embrace what’s happening in the world right now. We are living in history.”

Shinn says his school is known in Seattle as being a leader in social justice education and points to the city’s racial equity team in some schools, which works with teachers to drive the conversation about race. Shinn says the team helps teachers answer critical questions: “How are we going to teach teachers how to talk about race? How are we going to ensure that black and brown students are not being left behind?”

School districts and teachers are grappling with those questions about race across America.

District leaders from across the country have expressed remorse over the death of George Floyd, including superintendents from Broward County, Fla., and Milwaukee. Some have even condemned police brutality, including superintendents in Los Angeles and St. Paul, Minn.

But many districts don’t have clear plans about how to address and discuss race in their classrooms. Students are demanding action. Some are circulating petitions asking for anti-racist curriculum be added in schools.

In response to Floyd’s death, Chicago Public Schools sent an 11-page document to teachers called “Say Their Names” that included guidance for talking with students about racism, police brutality and activism.

Michie, who teaches in a Chicago public school with mostly Latinx students, applauds the effort but believes much more needs to be done. “I think it’s great that they did it, but I think we need a whole lot more,” he says. “I know there hasn’t been time yet, but I just felt that in Chicago Public Schools — and all school districts — this has got to be a sustained and deep commitment.”

Michie, who is white, says white teachers also need to step up during this time and not place the burden for curriculum around race and racism on black and brown teachers.

“I’ve sensed ... a hesitancy on the part of white teachers about addressing these issues,” he says. “For things to really change, white teachers have to also see it as central and drop the defensiveness and realize we have a lot to learn. I mean, if 90 percent of the students are black and brown, how can we not make issues of race and racism and racial justice central?”

White teachers, the curriculum is George Floyd and anti-racism. It's not the job of Black teachers to carry this weight. It is on us--this week & always. If we are not actively teaching against racism, if that is not a central thread in our curriculum, we are part of the problem.

— Gregory Michie (@GregoryMichie) May 31, 2020

Eighty percent of public school teachers across the country are white, according to 2015-2016 data from the National Center for Education Statistics, a number that has only reduced 3 percent in more than a decade.

“In general, we need to stop centering on whiteness ... and privileges of white people in education,” says Joe Truss, principal for the Visitación Valley Middle School in San Francisco, which serves about 400 students in sixth through eighth grades, many of whom he says are black, brown and immigrant. “Which also means moving the folks who have been marginalized and oppressed to the center of everything: the center of the curriculum, hearing their stories, the center of the pedagogy, learning and teaching how folks of color learn ... and having relationships that actually center kids of color.”

He says the current call to action for teachers to talk to students about race is important, but it’s an integral part of the curriculum at his middle school.

White people: We need white folks to use their white privilege and oftentimes their money to occupy all lanes of antiracist work. Don’t choose. White folk, have multiple cars. Caravavan towards racial justice. https://t.co/NFGXAPUA3Y

— Joe Truss - Culturally Responsive Leadership (@trussleadership) June 6, 2020

“I don’t think we necessarily think about the perpetual experience of being discriminated against or being bombarded with images or messages that, if you are a black person, you are less than a white person,” he says. “That’s a perpetual, ongoing routine trauma that people of color — black people — experience.”

As a result, Truss says, his teachers take a trauma-sensitive approach with their students because of the difficult experiences they are having in their neighborhoods and communities, including the death of George Floyd.

“When you see someone taking someone’s life in broad daylight, and no one is doing anything about it ... you’re being told your place in society,” he says. “So the best thing we can do as teachers ... is you’ve got to build the kid up. If they have some sort of understanding of what that is so that they can hold both things to be true: this is the way it is, but this isn’t the way it has to be. And you could do something about it and you should, as soon as you can and any way you can.”

And while ethnic studies, social-emotional learning and culturally responsive teaching aren’t new to his school, he understands why so many teachers across the country are now looking for more information on how to talk to their students about race.

Truss, who is also a consultant, says his latest virtual course for teachers, “Dismantling White Supremacy Culture in Schools,” has seen a dramatic increase in interest, with more than 700 people signing up. “I have done them in the past, and there was nowhere near the response that it’s getting right now,” he says.

He has also compiled a list of books around anti-racism to help teachers learn.

“It’s life’s work. It’s not about a moment. It’s not about doing the right thing, right now. It’s not about a 50-minute racial sensitivity course now that someone’s been killed again. It’s about asking the question of why it’s happening and what conditions would have to be present for it not to happen,” he says.

“It’s your responsibility as a teacher to learn about [black] culture, to learn about the history so that you can fairly reflect that to the boys and girls,” says Waynel Sexton, a retired elementary school teacher and consultant in Houston who was also George Floyd’s second-grade teacher. “We can’t just continue to present white history as United States history, we have to include everyone.”

When Sexton began teaching in 1970 at Frederick Douglass Elementary School, a black school, Houston’s school system was not yet desegregated.

“The integration system at that time was based on what was called the Singleton ratio, where teachers were integrated according to certain percentages in certain schools. And so sadly, a lot of brand-new white teachers went to many inner-city schools and experienced black teachers were sent out to white schools,” she says.

Sexton describes an environment where black and white teachers had intense conversations to bridge divides and form alliances. And, she says, it was a time when she had many conversations about race with her own students.

“I can remember talking with my boys and girls about Jim Crow,” she says. “And, because I’m Caucasian, I wanted them to know that we could talk about that together. And I think that sets a pattern for future conversations.”

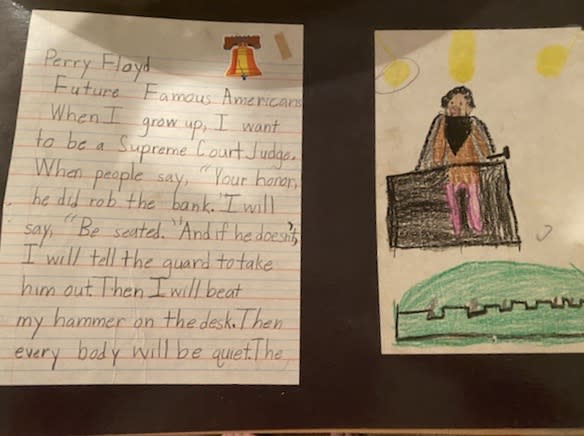

While she only had Floyd as a student for one year in the second grade, she kept a paper he wrote in her class about famous Americans and his desire to be a Supreme Court judge working in the field of justice.

“He’s certainly famous and he’s certainly advancing the cause of justice, not in the way that we would have wanted it to happen, not in a way that we could have ever imagined that it would happen,” she says.

Michie says he believes a key element to helping students understand and process racial inequality is to teach about the history of racism in conjunction with inequality happening today. “If we tag back and forth between what’s happened in history and what’s going on now, and specifically ask students to make connections, I think that not only the history becomes more alive to them, but they see how the inequities and injustices today are connected to things that happened in generations past in important ways.”

Shinn says part of the education happening in his classroom now involves talking not just about the protests but about the policies that need to change as well. He says he recently showed students how to find their city councilperson and write a letter. “I literally just shared my screen with them and ... I typed up a very quick email to my city councilperson about how I felt about what’s going on with the Seattle Police Department. And I just hit send,” he says. “I think that right now students want to feel agency. They want to feel like they have the chance. And we should equip them as teachers, for them to feel that agency to make them feel like they are doing something different.”

Shinn says he believes the more agency he can teach his students, the better chance they have to change the world and the landscape of politics in America.

“They are going to be the reason that Congress changes. They are going to be the reason that we’re going to see a new City Council taking harder stances on things,” he says. “Students are fed up. Students have had it. They’re done. They’re sick of living in a world that’s trash. They want something better, and they deserve something better. And that’s what they’re going to get.”

Read more from Yahoo Life

#SayHerName: Tepid response to Breonna Taylor's killing has many wondering which black lives matter?

Want daily lifestyle and wellness news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here for Yahoo Life’s newsletter.