'The Empire Strikes Back' at 40: What the 'Star Wars' sequel's iconic special effects owe to Ray Harryhausen

It’s only appropriate that Ray Harryhausen and The Empire Strikes Back are celebrating milestone anniversaries in the same year. 2020 marks the 100th birthday of the special-effects pioneer behind vintage Hollywood spectacles like The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and Jason and the Argonauts, as well as the 40th anniversary of the second — and best — installment in Star Wars’s Skywalker Saga.

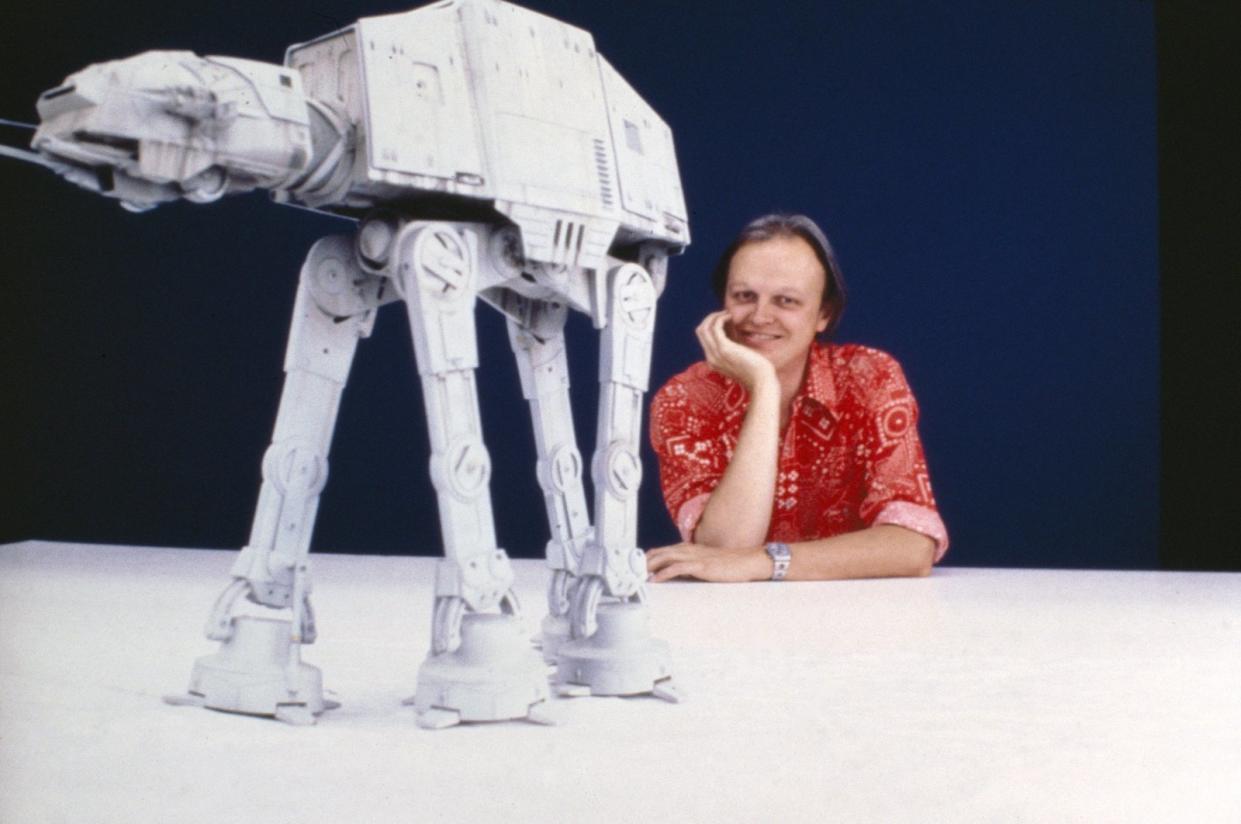

But they have more in common than the calendar year: The AT-ATs and Tauntauns that walk through Empire are inspired by Harryhausen’s menagerie of stop-motion creatures, from cyclopses to krakens. “They had character, they had performance and they had purpose,” says Dennis Muren, who parlayed a childhood spent watching Harryhausen’s films into a groundbreaking career as a Star Wars F/X legend. “They were wondrous to look at, and the designs of the shots were dynamic. Ray’s work grabbed you emotionally, because it began with him. I’m the same way: being emotionally connected to the performance and design of a character who, simply put, looks really neat.”

Currently the Senior Visual Effects Supervisor and Creative Director at Industrial Light & Magic, Muren first joined George Lucas’s pioneering visual effects studio in 1976, when it was still making and photographing spaceships in a Van Nuys warehouse. After Star Wars blew up at the box office, Muren followed ILM to the Bay Area as Lucas charted course for a return trip to his far, far away galaxy. “It was the hardest film by far,” Muren says of how The Empire Strikes Back came together behind the camera. “Everything just got bigger. The spirit of the film was still fun and adventure, but it had more romance, it had more action, the Empire was bigger and the universe was bigger than we thought on the first movie.”

Muren’s role also expanded with Empire, as he took point on directing the fleet of miniatures that play a major part of the film’s iconic opening set-piece on the ice planet, Hoth. With the advent of digital technology still many years away, Muren and his team brought the Rebel’s herd of tauntauns and the Empire’s squad of AT-AT walkers to life by hand. And through it all, he followed the example established by Harryhausen.

“I always think of the Cyclops from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, who comes out of his cave roaring and angry, and his hands are up because he’s ready to grab one of the sailors,” explains Muren, who later won his first Oscar for his work on the film. (He currently has nine statues, the most of any living person.) “That’s what I always strive to put in my work: that there’s a reason for that creature to be there. You’re not just giving the audience an effect: You want them to feel something from it, whether that’s ‘Oh my God, that’s amazing,’ or ‘Oh, that’s really creepy,’ or ‘Wait, that’s impossible!’”

In honor of Empire’s ruby anniversary, Muren walked us through the seemingly-impossible task of making the Hoth sequence, and his own close encounter with his F/X hero.

Yahoo Entertainment: You said that The Empire Strikes Back was the hardest Star Wars film to make. What was the reason for the degree of difficulty?

Dennis Muren: Well, The Phantom Menace may have been equally difficult, because there was a lot of real groundbreaking work on that in terms of getting all the digital stuff to work. But we had two supervisors on that. For Empire, we had just moved up from Los Angeles, and only brought about 12 people up from the 50 in L.A. and had to hire locally just to get the thing done. All of us working on it wanted to top ourselves, and George had already done that with the designs. The number of lands and battles you saw in Empire was at least five times more than you saw in Star Wars. You had an ice planet and a city in the clouds — how are you going to get that to look right?

Doing any kind of compositing over a light-color background is very, very hard. And the whole movie was full of that in addition to your normal space battles. The vision was so big, and we had a couple of years to do it, but it took us so much time to get the fire to do it and the people to do it. We all wanted what George wanted, which was also what the audience wanted: to show you that this universe is so much bigger than what we saw in Star Wars.

What was the most challenging part of the Hoth sequence specifically?

The opening tauntaun shot was one of the most difficult things, and the most interesting. The story behind that was that George had brought back this helicopter shot from Norway [where the Hoth exteriors were filmed], and it was about 200 or 300-feet off the ground with the cameras looking straight down. He didn’t know whether if that shot was going to be necessary to the movie, but at the very end, he said, “Yes, it’s necessary to have this shot. Do you think there’s a way you can add a Tauntaun to this?”

There wasn’t! There were no tracking markers on the ground that would have helped us make the stop motion camera map exactly with the moves the helicopter made, and then we could have combined that with an optical printer. But none of that stuff was there. I thought about building a big model, but I didn’t think it would work with the background. George said, “Well, just think about it.” I spent 15 minutes thinking about it, and figured it out in 15 minutes! I learned an amazing lesson from that: There’s usually an answer, there’s always some way that you can fiddle around with what you know to attempt. If I had stopped thinking at 14 minutes and 59 seconds, we wouldn’t have had that shot in the movie.

The tauntauns definitely feel very Harryhausen in their design and behavior. Did their form match what you could accomplish then with stop-motion or did the stop-motion dictate their form?

George had the idea for a galloping horse kind of thing, and I think Ralph [McQuarrie] and Joe [Johnston] worked on the design. I was involved in how we were going to create a setting that looked like it was going to be real, and wouldn’t be encumbered by any of the cameras. I don't know how many shots we had of it — maybe 12 or 15 or something like that, and they were some of the last ones we did. There were a couple that George added right at the very end of that. It was like, “We can finally take a breather after two years, but no, there’s one more shot!”

I remember connecting to them very strongly as a kid — I always through they’d be fun to ride.

That comes from the design and purpose of it. It doesn’t act like an evil creature: It’s a fairly big, bulky thing and it actually looks kind of cute with a horn and steam coming out of its nose. It’s not a creature that could kidnap you or anything — it’s just a beast of burden. That’s true of all the Star Wars movies: The behavior is familiar, so the audience can relate. Even with the designs of the spaceships; I tried to show how they would bank off to fly to another planet or something, like an airplane would do in the air even though there’s not gravity in space and that would never happen. It looks really neat and you can relate to it.

In terms of the AT-AT walkers, that’s a case where you’re bringing character to a non-living thing. There’s behind-the-scenes footage of the ILM team studying elephants for movement reference.

When we saw the designs, we thought they were kind of like big animals. We went to an animal park in Dunn, California, and put a bunch of chalk marks on the elephant and had it walk by left to right and right to left with the camera on. That gave us the weight; those things would have weighed thousands of tons, and we had to make it look like they had gravity or else they were just going to look silly — not as powerful and as evil as they're supposed to look. We also shot the elephants in slow motion to make them look even bigger, and observed traits like how far up the knee goes up and how far forward the body travels. Does the foot just lift up? Does it drop back down again? All that stuff was used as a basis so that when we went to animate, we had a body part to do that.

We also had some really good equipment to look at the frames as we were shooting them and make sure the animation was working well. Like now, there's all sorts of stop-motion photographers, and ours wasn’t done like Ray would have done it where you couldn’t tell if you made a mistake and could go back and say, “Did I move this too far?” We were able to compare and say, “Oh yeah, we did move it too far,” and then change it to move to a better place. So it's probably more of a fluid motion than you might have seen before and that was important. Any sort of chatter in the stop-motion looks like the mechanics of the walkers. They're all mechanical anyway, so there's got to be little bumps and grinds in the motors. So that adds to the feeling, you know?

Besides Hoth, what was your favorite sequence to work on?

I don’t know — they’re all so different! [Laughs] I really like the asteroid sequence; that might top Hoth a little bit. It was also really difficult, but a lot of fun to do. George wasn’t interested in the beats of the action, but the attitude. It had to have a certain clarity to see what was going on, which was difficult because the asteroids were coming in from any direction. I did a mock-up of that sequence and realized that everything had to be based on the Millennium Falcon blasting through the asteroids. We came up with the idea of having all the asteroids going in one direction, from one side of the screen to the other, and then you could show how the Falcon makes evasive maneuvers.

Did you get a chance to meet Ray Harryhausen before his death in 2013?

Oh, yes. I was probably about 14 at the time, and he used to be in the phone book as was almost everybody else in those days in L.A. I called him up, and he was living up in Malibu, so my mom drove me two hours up to his house, and I met him and his wife. They were just the nicest couple in the world. They invited me in for an hour or two, and we kept in touch. As I got older, I went back to his garage and showed him my home movies, and he showed me some of his early home movies. He was a kindred soul. He later moved to England, so I didn’t see him very often after that.

Did he ever visit you while you were making Star Wars or Empire?

No, but I did see him while I was working on Dragonslayer. We were at the same studio in England, and he was making Clash of the Titans. I think I brought him by to show him the dragon, and the rear-projection work. We were working on the next step beyond stop-motion, which was the combination of animation with a motion-controlled motorized camera. He didn’t entirely relate to that, and I can understand why: It could take five days if you’re lucky to get a full shot. At the end of the day, [his method] didn’t have quite the realism that ours ended up having, but he also had the energy to just get in there and grab the figure with his hand and spend the next eight hour animating it.

After Empire and things like the Tauntaun sequence especially, I realized that we needed to get away from stop motion and try and look for something else. I would say that we didn't get the tauntaun to move quite as much as we wanted to, and there were some shots that we didn’t quite finish. But George was utterly accommodating about everything, and there was a feeling of real accomplishment when it was all over. Empire just opened everything up: You can see there’s a lot more stories you can tell, and they’re still going on.

The Empire Strikes Back is currently streaming on Disney+.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment: