The True Story of the Scientist at the Center of ‘Oppenheimer’

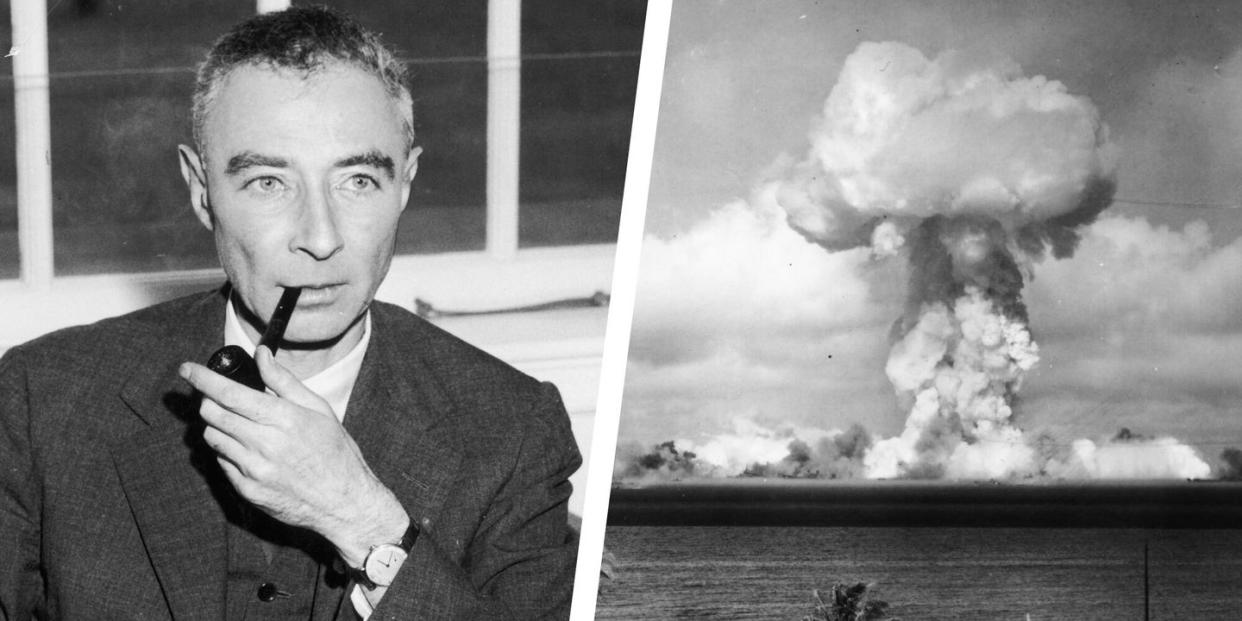

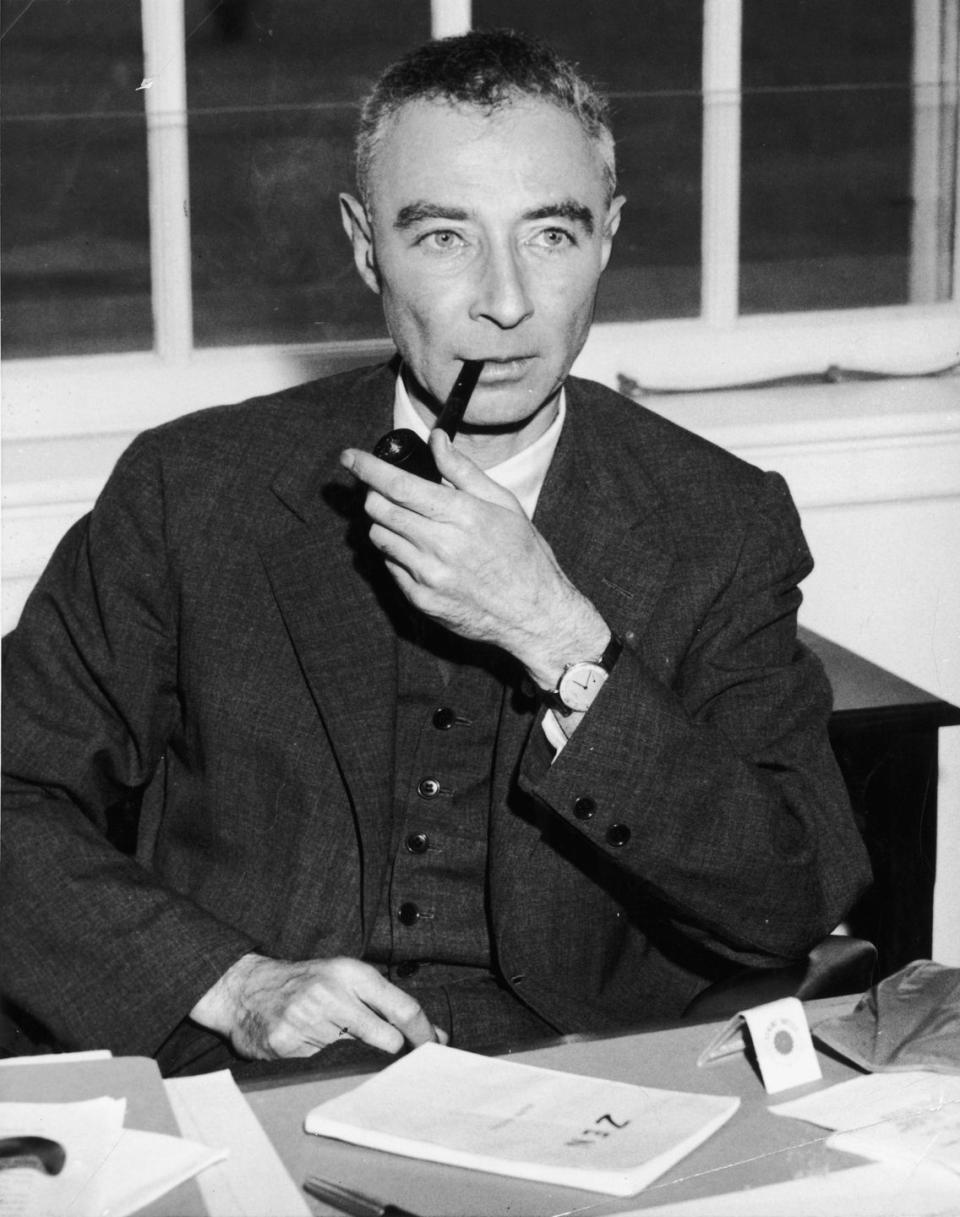

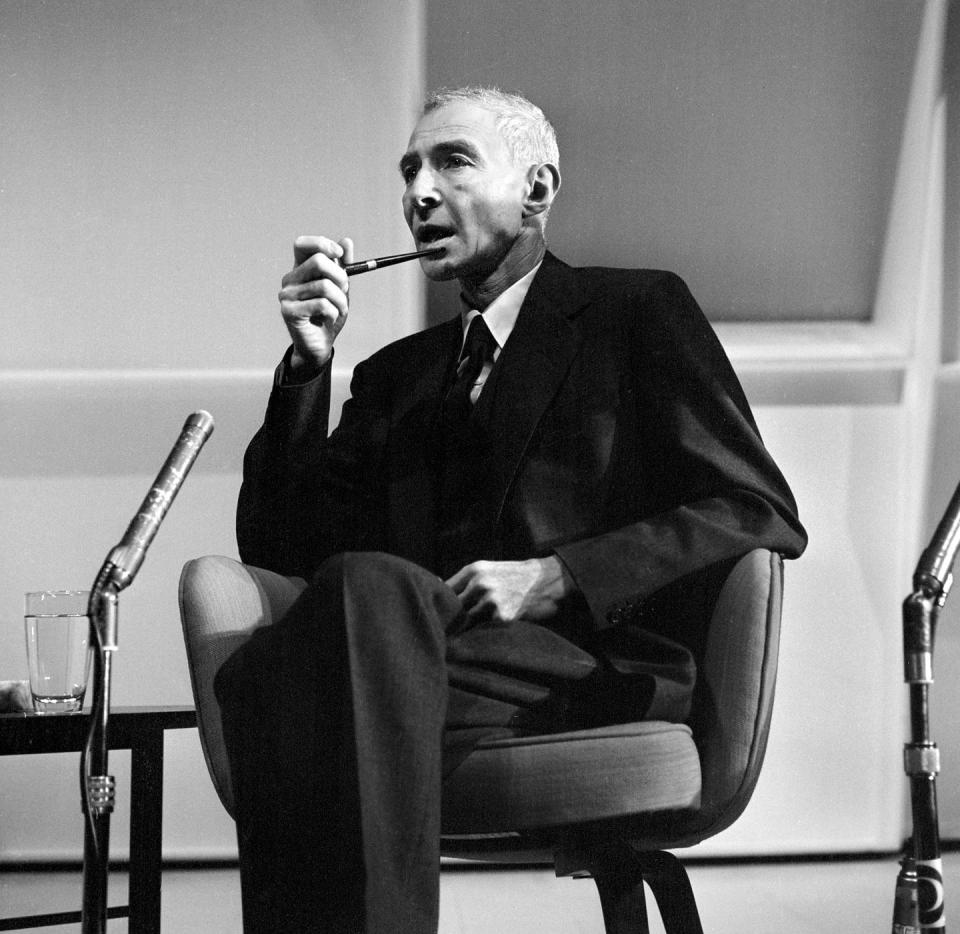

J. ROBERT Oppenheimer’s public persona is as murky as his legacy is massive—quite literally world-shifting. Oppenheimer, at the center of Christopher Nolan’s new biopic of the same name (now in theaters), is primarily known as a leading physicist and leader of the Manhattan Project, which created the atomic bomb (he’s also been referred to as the “father” of the atomic bomb), consequentially deployed by the United States in World War II.

The scientist is played by Irish actor Cillian Murphy (28 Days Later, Batman Begins) in Oppenheimer, which, in typical Nolan fashion, is a visually and sonically expansive (and expensive) undertaking of its own, with a reported $100 million production budget and “gold standard” IMAX filming.

Which is to say, a whole lot more people are about to learn about the controversial geek who happened to be key in unleashing nuclear weapons upon the world. But Oppenheimer’s personal life and politics, more complicated than they might first seem, are worth teasing out. Whether you’re grabbing tickets to Nolan’s latest, skipping it, or combining it with Barbie for the oddest viral double bill of the year, here’s what you need to know about the film’s elusive subject, why he matters, and how he’s often misunderstood.

Who was J. Robert Oppenheimer, the man behind the atomic bomb, really?

He was born Julius Robert Oppenheimer on April 22, 1904 in New York City. His father, a German immigrant, helped make his family’s considerable fortune working in textile importing, while his mother was a painter. Oppenheimer grew up in a Manhattan apartment reportedly decorated with artwork by Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and Paul Gauguin (casual!).

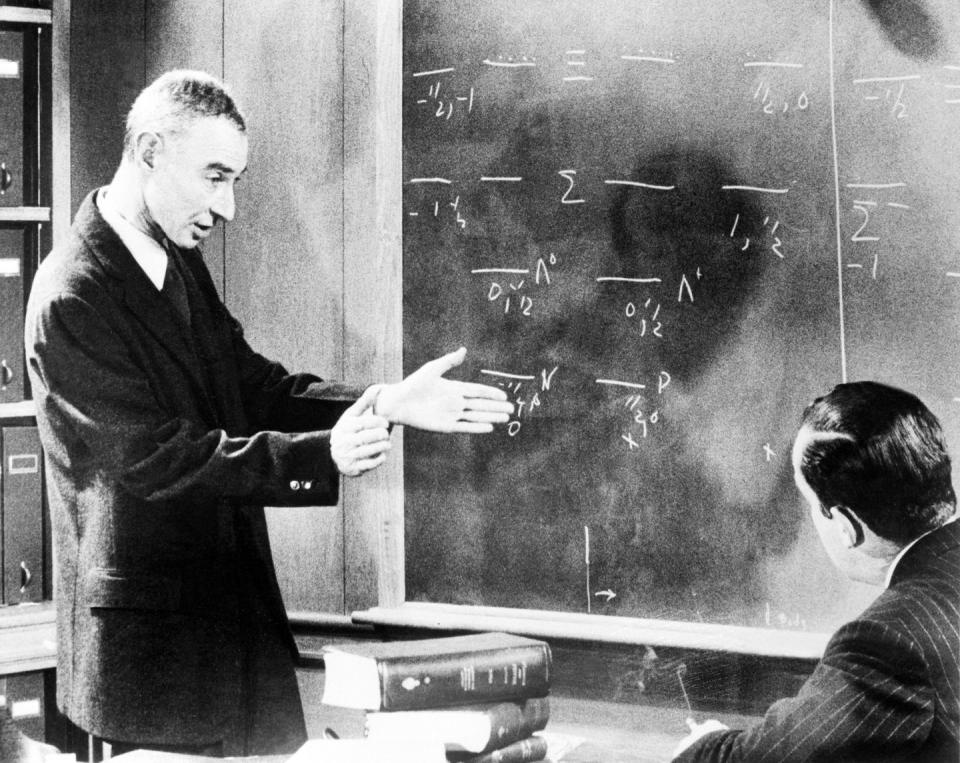

Oppenheimer became an ace student, and while an undergrad at Harvard University, excelled in (of course) physics, but also chemistry, Latin, Greek, poetry, and Eastern philosophy. He followed up Harvard by doing research at the University of Cambridge in England, but uninspired by rote lab work, moved to the University of G?ttingen in Germany, to study then-revolutionary quantum physics with pioneers in the field. He got his PhD, and, quickly, a sterling reputation. He accepted dual offers to teach at both Caltech in Los Angeles and the University of California at Berkeley, splitting his time and influencing a generation of top physicists.

“His lectures were a great experience, for experimental as well as theoretical physicists,” the late physicist Hans Bethe said of Oppenheimer. “In addition to a superb literary style, he brought to them a degree of sophistication in physics previously unknown in the United States. Here was a man who obviously understood all the deep secrets of quantum mechanics, and yet made it clear that the most important questions were unanswered. His earnestness and deep involvement gave his research students the same sense of challenge. He never gave his students the easy and superficial answers but trained them to appreciate and work on the deep problems.”

While Oppenheimer dabbled with Communism in the 1930s, meeting Communist students and supporting the left-leaning Republican side in the Spanish Civil War, he never actually joined the Communist Party. Yet this dalliance would come back to bite him (more on that below). It should be noted that Communism was widely seen as a viable alternative to fascism at the time, and Oppenheimer was reportedly enraged at the suffering of Jewish relatives in Nazi Germany.

But the start of World War II would put Oppenheimer’s political interests on the back burner, and upend the trajectories of physicists in ways no could have imagined.

How did the Manhattan Project come about?

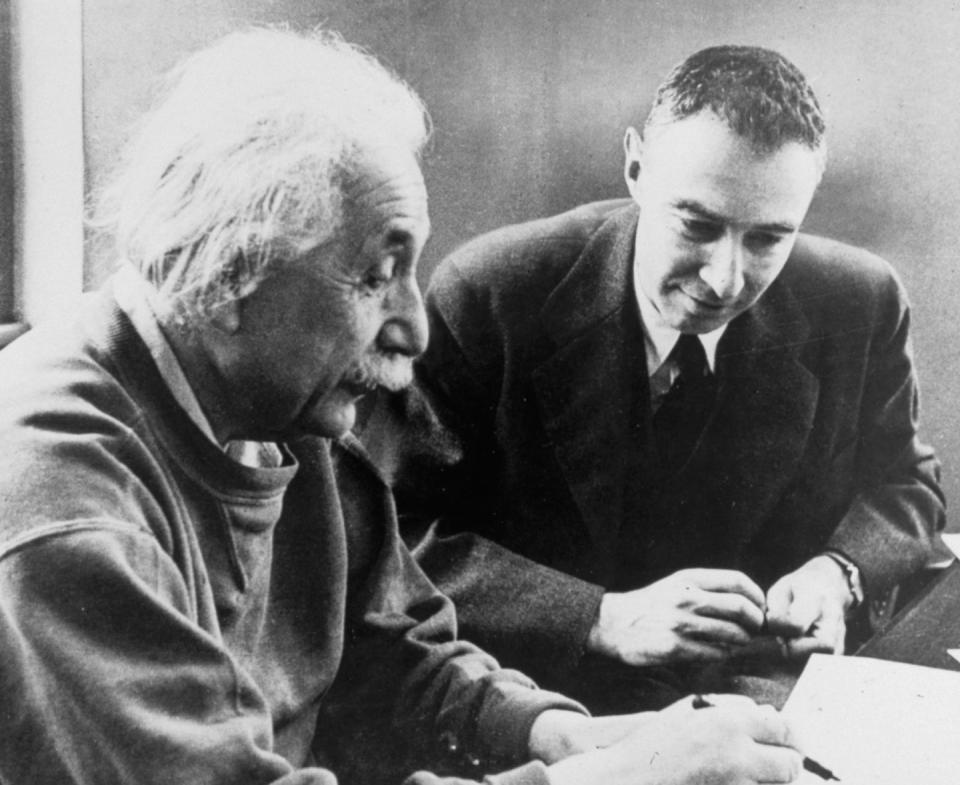

Following the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939, renowned scientists including Albert Einstein (yes, that Einstein) warned U.S. officials of the grave danger should the Nazis be the first to create a then-theoretical nuclear bomb.

Enter Oppenheimer: The U.S. Army marshaled American and British physicists to figure out how nuclear energy could be distilled into unparalleled military force. The code name for the effort was the Manhattan Project, and Oppenheimer was chosen as administrator. He oversaw several covert labs, and famously constructed one in the middle-of-nowhere desert plateau of Los Alamos, New Mexico.

When did the atomic bombs actually go off?

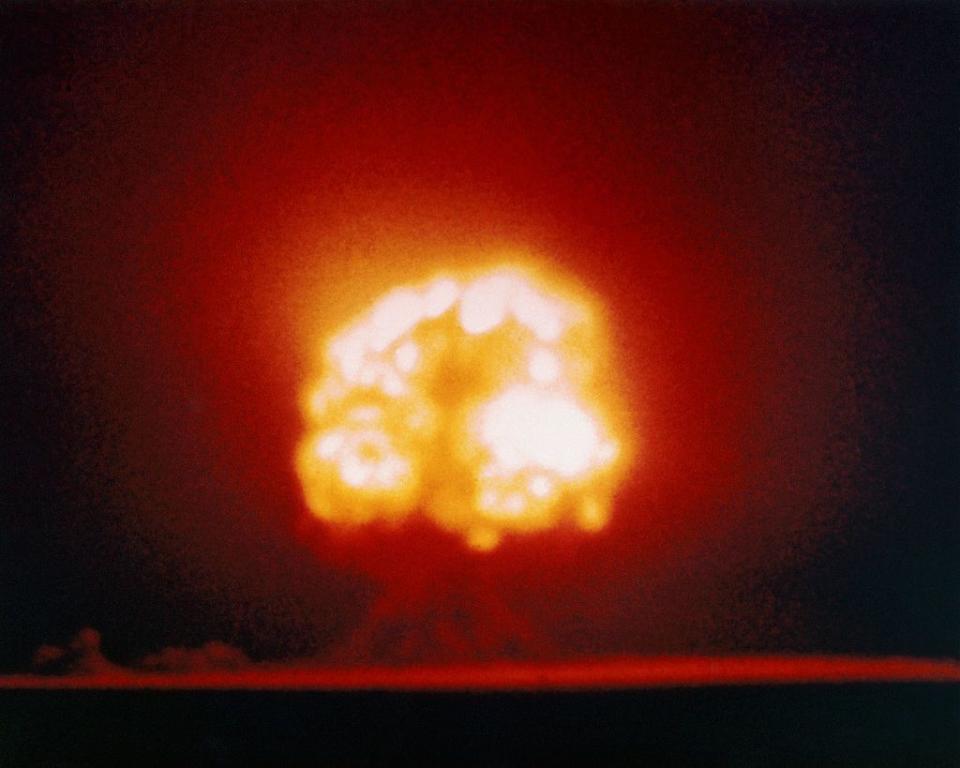

Indeed, the Manhattan Project was a success on its own terms: Work in Los Alamos (as depicted in Oppenheimer) led to the initial test nuclear explosion, on July 16, 1945, in a remote area of New Mexico near Alamogordo. (For what it’s worth, according to the Los Alamos National Laboratory, the “atomic” or “atom” bomb refers to a bomb “that relies on fission, or the splitting of heavy nuclei into smaller units, releasing energy.” Hence why they’re also called nuclear bombs.)

The unleashing of the atom bomb actually came after Germany had surrendered in WWII. Still, the U.S. dropped two nuclear bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Japan, in August 1945, with Japan being an active Axis power against the American and British Allies. Those nukes were the first, and to this day only, nuclear bombs used in warfare.

What happened to Oppenheimer and his career after the atom bomb?

Only a couple months following the bomb drop in Japan, Oppenheimer resigned from his Manhattan Project post. In 1947, he became the head of the Institute for Advanced Study, a community of scholars, and also served as chairman of the government agency known as the General Advisory Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) until 1952. He openly opposed development of the hydrogen bomb, another far more powerful nuclear weapon that came to fruition but has never been deployed in battle.

By 1953, Oppenheimer’s favorable view in the eyes of U.S. officials began to crumble. Amid the Cold War-era Red Scare, he was alerted to a critical military security report that brought up his past associations with Communists, along with his opposition to the H-bomb.

Oppenheimer faced further scrutiny in a headline-making security investigation. In 1953, though cleared from accusations of treason, he lost his access to military secrets and his AEC position. He subsequently got the cold shoulder from certain corners, and reportedly never quite recovered his spirit.

Was Oppenheimer a good guy, or a freaky “destroyer of worlds”?

Oppenheimer’s thoughts on harnessing science for destruction, a mission with which he is inextricably bound, are more nuanced that they might appear on the surface.

“We knew the world would not be the same,” he recalled of the first detonation of the atomic bomb under his stewardship. “A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent.”

And okay, yes, he did say the ominous words widely attributed to him: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” But it is a quotation.

Long interested in Eastern philosophy, Oppenheimer had turned to Hinduism to help make sense of what he had wrought upon the globe. The famous, or infamous, “destroyer of worlds” line comes from Hindu scripture and is poorly understood. As Wired writes, in Hindu thinking, “the great god is not only involved in the creation, but also the dissolution.” The line Oppenheimer quoted in light of the atomic bomb refers to a kind of “world-destroying” event that is ultimately left in the hands of the divine. That might not provide any easy answers, but it’s pretty clear that Oppenheimer’s interest in this spiritual perspective was sincere.

How did Oppenheimer die?

Oppenheimer died rather early in life, from throat cancer, at the age of 62. He passed on February 18, 1967, in Princeton, New Jersey. But he had been, at least, vindicated in some ways by the U.S. government following his Cold War persecution. In 1963, President Johnson awarded the physicist the highest honor of the AEC, called the Fermi Award, honoring the most formidable scientists for lifetime achievement in utilization of energy. And no one will seriously talk about nuclear bombs, or watch Oppenheimer, without at least briefly flashing to his momentous life and career.

You Might Also Like