The tumultuous final years of Janis Joplin – by her brother and sister

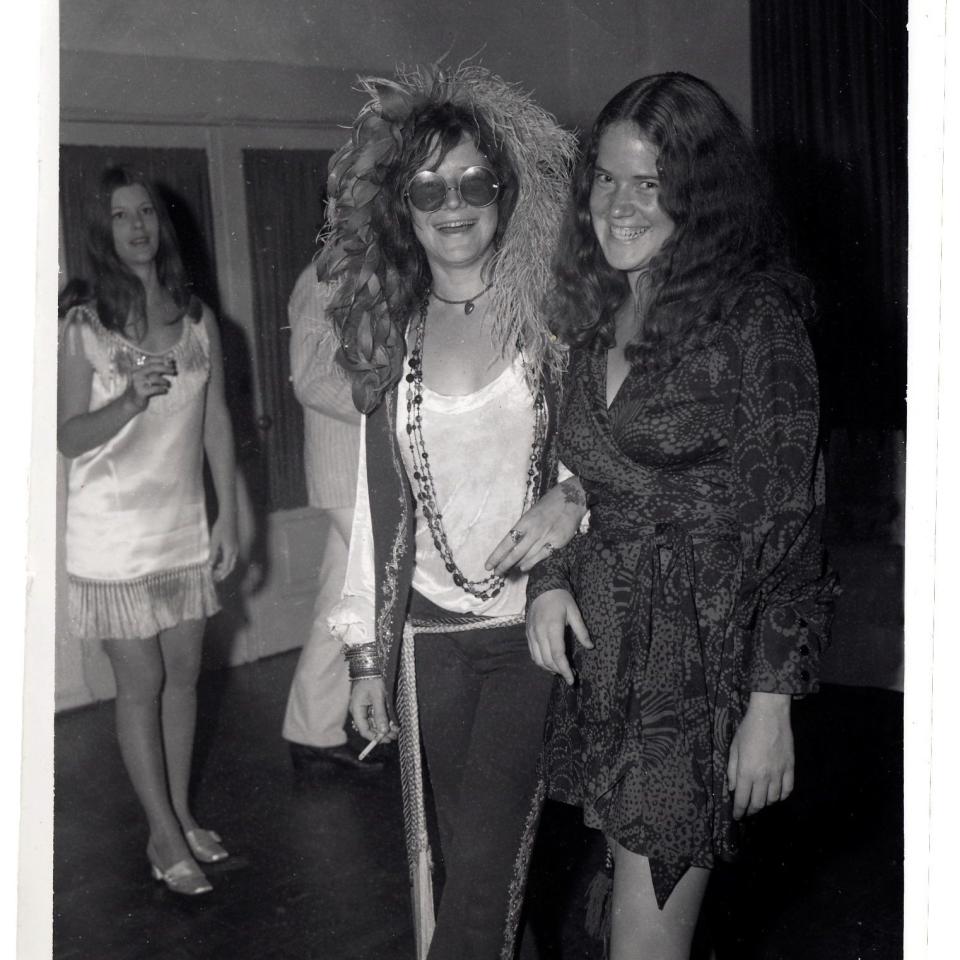

On August 14 1970, Janis Joplin went home. Thomas Jefferson High School in Port Arthur, Texas, was holding a 10-year reunion. Joplin rocked up in hippie flares, a scoop-necked T-shirt, a feather boa that she wore as a hat, and her trademark round, colour-tinted sunglasses.

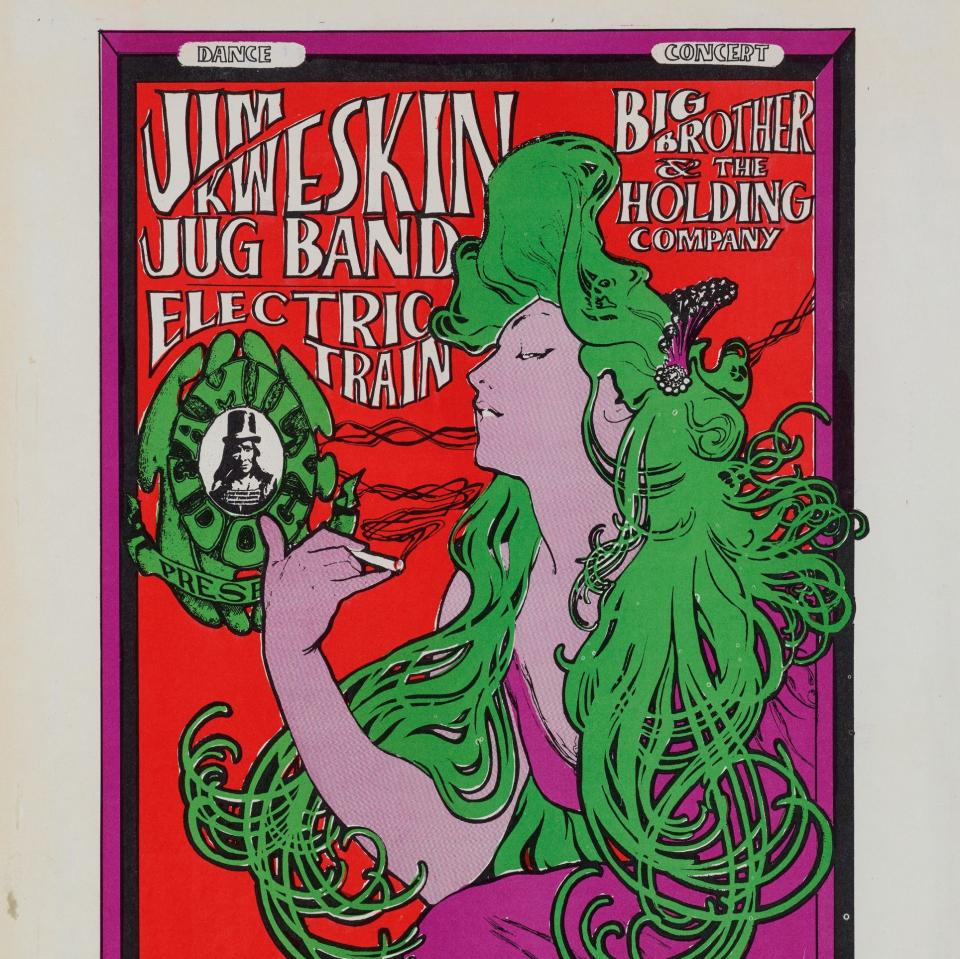

At the time, the 27-year-old singer and songwriter was one of the biggest counter-cultural forces in America. An incendiary performer on- and off-stage, she was a hippie style icon and feminist trailblazer who’d made her name on the San Francisco scene as frontwoman with Big Brother and the Holding Company. Her incredible blues range saw her credited as having “The Voice of a Lady Leadbelly”, as the New York Free Press headlined a February 1968 profile.

The previous summer Joplin had been one of the star performers at Woodstock, managing to cut through the stoned fug and 2am start time with an earth-shaking performance. As The Who’s Pete Townsend wrote in his memoir, Who I Am: “She had been amazing at Monterey, but tonight she wasn’t at her best, due, probably, to the long delay, and probably, too, to the amount of booze and heroin she’d consumed while she waited. But even Janis on an off-night was incredible.”

Indeed. As The Washington Post wrote in April 1968 of her stage persona: “She screams, she stomps, she jumps, she quivers, she flails her arms, she flings her great wild mane like an unbroken pony.”

Later that summer of 1970, Joplin would begin work on her second solo album, Pearl, which would feature some of her best-known songs, including her cover of 1963 R&B track Cry Baby and her own (co-written) Mercedes Benz. But before that, there was that detour back to Port Arthur, the small, conservative Texan community in which, as a beatnik-channelling teen rebel, she’d never felt at home.

“It was a formal event and it was an awkward fit!” recalls her 72-year-old sister, Laura, laughing. She accompanied Janis, six years her elder, to the reunion, and wore a dialled-back version of her sister’s fabulous freak-out garb.

“Everyone else was in straight, middle-class clothing and teased hair. There was a sense they didn’t quite know what to do about her. But in my mind, and in Janis’s, they should have made her attendance and her success one of the central points to celebrate – ‘Look what someone from our high school has achieved!’

“However, the guy running things thought in terms of how many people had law degrees. It was only when the president of the class said, ‘What about Janis Joplin?’ that everyone stood up and applauded.

“I think that hurt her feelings. No matter what she did, she could not get applause from her classmates.”

Even then, the recognition was miserly. At the reunion, Janis was symbolically gifted a tyre, to represent “that she’d come the farthest”. And that was meant literally. “That’s what I find most insulting,” says Laura, audibly pained 51 years later. “Instead of being the person who had reached the greatest visible recognition in the country, Janis got a tyre for having travelled the longest distance.”

Later that same night, the Joplin girls went to see Jerry Lee Lewis play in Port Arthur. Janis was proud to be able to take her little sister backstage to meet the man, part of “a desire to show she had connections with powerful people.”

Nonetheless, it was an “unfortunate experience. He couldn’t have been more rude. He looked at me and looked at her and said: ‘You wouldn’t be bad-looking if you weren’t trying to look like your sister.’ The jerk that he is,” Laura says, witheringly. “That really hurt Janis. So she punched him.”

Less than three months later, Janis Joplin was dead. Half a century on from her heroin overdose in Hollywood – midway through the Pearl recording sessions – her visceral, moon-shooting, too-close-to-the-sun artistry and personality are opened up in a lavish new book.

Janis Joplin: Days & Summers: Scrapbook 1966–68 is centred on exactly that: Janis’s own scrapbook from those tumultuous two years, the period in which she broke into the international consciousness at 1967’s Monterey Pop Festival and then, the following year, had career-launching US hits with covers of the soul standard Piece of my Heart and George Gershwin’s Summertime. It features newspaper clippings, press photographs, far-out Sixties concert poster art, letters and postcards home, doodles and, in her own handwriting, Janis’s diary entries. “Speaking of England,” begins one 1967 note, “guess who was in town last week – Paul McCartney! (He’s a Beatle.) And he came to see us!!! SIGH.”

This ambitious – not to mention pricey – limited-edition book, in part curated by Laura Joplin and her brother Michael, 67, also features pages from an earlier scrapbook, dated 1956 to 1959 and kept by Janis while she was at high school. Alongside those DIY pages are revealing interviews with myriad friends, collaborators, peers and admirers, including Fleetwood Mac, Grace Slick of Jefferson Airplane, friend Kris Kristofferson (with whose song, Me and Bobby McGee, Janis had a posthumous US number one in 1971), and fans Michelle Phillips, Jimmy Page and Chrissie Hynde.

To quote the last of these, who saw Janis perform in in Richfield, Ohio, “there was just no one else like her – total rebelliousness, abandon, musical excellence and total connection with everyone in the audience. Pure magic. Everybody loved her. She gave us a voice that was anti-establishment, and I’ve lived by it ever since.”

This is a deeply personal, kaleidoscopic, hippie-vivid portrait of a woman finding her way in the world, and a window into the dizzying contours of America in the mid- to late-Sixties. Harder to divine is the darkness inside that compelled Janis to overindulge to the extent that it killed her. As Kristofferson describes her in his afterword, which comes in the form of poem titled Epitaph, this was a woman “born so black and blue”.

“Janis’s scrapbook has been a personal family thing for such a long time,” begins her brother Michael, down the line from Arizona, “and we’d all looked at it, and laughed and pointed and wondered and cried. And we never felt like sharing that personal, gut-wrenching family thing. But after a while it became obvious that it was something of not just interest but importance. After keeping it that way for decades, it just seemed the right time to do something with it.”

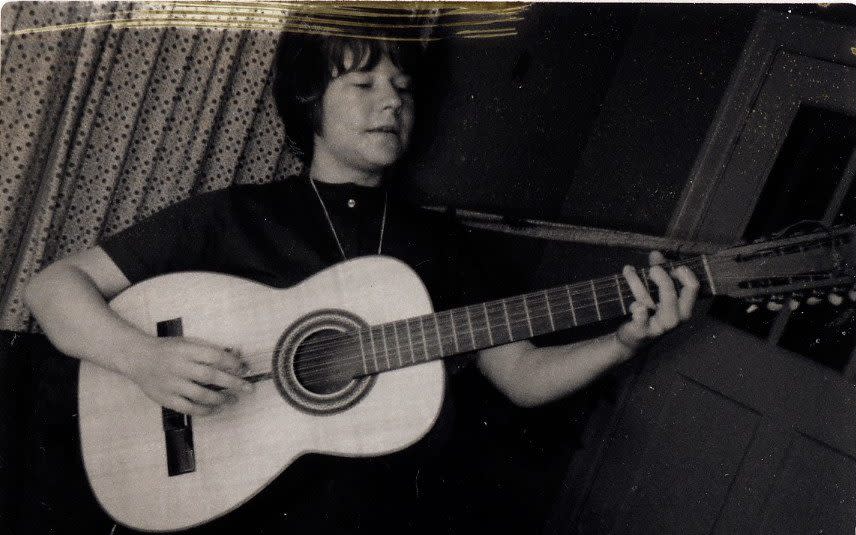

As Laura writes in the introduction, from childhood her big sister was always keen on “logging” her life.

“It certainly was a steady part of who she was from early on,” she tells me, speaking on the phone from California. “That may have been a reflection of our mother – she chronicled our lives on photo scrapbooks. Janis’s scrapbook told you a lot about what she valued, what was important to her, what gave her joy. I remember her working on that scrapbook in her bedroom, cutting things out and doodling. So there’s a sense of her vitality whenever I look at it. It feels more alive.”

Janis stayed in touch with her family after she moved to the West Coast in pursuit of her musical dreams. Michael remembers that move as “the logical progression. There wasn’t much in our town. If you wanted to work at the oil refinery, that was fine. But our parents supported us – if you wanted make music or art, go for it.”

In the talismanic summer of 1967, the family made the long car journey to visit San Francisco and see Janis at home and, as it were, in action. For Laura, who had just graduated from school, and Michael, then 14, it was “mindblowing” to tour Haight-Ashbury with their big sister and see her perform with Big Brother at the Avalon Ballroom. Michael even had a go at manning the concert lighting rig.

“I’m a wannabe hippie in every aspect,” says Michael, who now makes a living as a glassblower. “And I was so proud of Janis. Everybody in there treated with us absolute respect. There were all in awe of her, and [to us] they were helpful, respectful and kind: ‘Yeah, come on and do the light show! Watch the dancing! Listen to all this!’ Big Brother showed up, and they and the dancers and the hippie freaks were proud that we were there. They were protective, too. They weren’t just Big Brother – they were big brothers.”

For Mr and Mrs Joplin, it was a different experience. “They were totally out of their realm,” remembers Michael, “so they were really uncomfortable. But they could see that something was happening. They were small-town Texas people, so just the city itself was mind-blowing. And, of course, nobody knew at the time that the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco, in that Summer of Love, was changing history. We just knew something was going on, but nobody knew what.”

Alongside Janis’s mesmerising appeal as a blistering, unfiltered singer was her expression of raw sexuality. Even in the go-go late Sixties, that set her apart. “Part of [her] force is an open sensuality,” wrote The New York Times in April 1968, “with no tinge of coyness or come-on.”

“The sex thing they keep trying to lay on me,” she told the newspaper, “is always in the receiver’s head, which is where it should be. If I turn anyone on that way – great! Because that’s what it’s all about.”

But it wasn’t entirely accidental. Michael says his sister was a great “salesperson”, meaning: “She knew how to talk to the press, be available to the press… She was trying to sell the music and herself.” Equally, Laura points out, “There wasn’t a cerebral Janis and a [separate] sexual Janis. Her entirety was an expression of her art, and sexuality was part of that.”

Likewise, she adds, her sister’s fashion sense. “Our mother raised us to be creative about we wore. Mother sewed, and she always got us involved with designing the clothes we were wearing. So we were using fashion magazines, going to the store and picking fabric. Both Janis and I sewed and made some of our clothes. Mother thought that was a basic skill that women needed to know.

“And Janis just took it farther. She combined that knowledge of fabric and shaping it for your body along with her artistic flair. So it really grew.” The bangles up her forearms, the feathers, beads, headgear and layers “all became a real sense of her – decorating your body as an expression of who you are”.

But even from early on, there had been a sense that Janis was overdoing everything. Michael remembers an early visit home when his sister was clearly “strung out”, as he writes in the book.

“She was obviously not well. I didn’t really understand what was going on, but she came contrite and wanting something different from what she had. And rightly so – she knew that [she had] some problems. Drugs and alcohol were not treated the same as they are now. People were like: ‘You just have to get your act together and everything’ll be OK.’ That’s what she came back to do, to get healthy and to figure out how to proceed in life in a more rational way. But she didn’t know what that was.”

Does he mean strung out on heroin? “Ah, well, I mean… I’m still protective of my sister, so I don’t like saying a lot of that. But she was strung out on drugs, and drinking, and being poor as bejesus, and not eating. She was trying to stay afloat, and not able to.”

Nonetheless, her good friend and Big Brother bandmate Dave Getz is quoted in the scrapbook thus: “You can’t talk about Janis without talking about heroin.”

“There’s probably some truth in that,” allows Michael. “People have accused me of trying to protect her, and of course I do. But she did heroin. She did massive amounts of drugs and alcohol, and she slept around. What am I going to protect her from? So yeah, heroin was definitely involved in her life. She liked to do drugs and alcohol and get laid. What can I say? Everybody did.”

In January I interviewed Todd Rundgren – who, like Janis, was managed by the fearsome Albert Grossman – and the producer recalled his ultimately ill-fated attempts in early summer 1970 to prepare the groundwork for the recording of Pearl. “I hadn’t worked with an artist like her before,” he told me. “I was very much about the musical aspect, getting everyone together to do a performance in the studio somehow, and not mess around too much with the psychology or play head games.

“And Janis, I think, hated making records. She loved playing live. That was her life – to get up in front of an audience, freak out and do her thing. But she was just never comfortable in the studio because there was no audience.”

Equally, he added, “she in some ways was like a crazy teenager. She’d suddenly go off on a whim of some kind. I recall being in her house in Mill Valley [near San Francisco], and a bunch of people are coming in with songs for her, and then I get a call in from Janis: ‘I’m gonna be late, I’m at the police station!’

“Five minutes later, I walk past her bedroom, and the door’s open and she’s in there with some guy! She’s calling from her own bedroom, making excuses for not showing up because she doesn’t want to get out of bed with some guy she’s picked up the night before!”

Rundgren eventually left the project after recording moved to Los Angeles. As he admits, “it became apparent that I didn’t have the touch to get her to deliver in the studio. But after that they formed a band for her and that helped a lot – she finally had a musical unit she could interact with, and abandon herself to. And they found another producer, Paul Rothchild, whose style was completely different from mine. Mine was: ‘Let’s make some music in here.’ His was: ‘Let’s make everybody feel real good in here, and maybe the music will happen.’”

The sessions, though, came to an abrupt halt on October 4 when Janis was found dead in her hotel room.

For Mick Fleetwood, who knows of what he speaks, it was a sadly inevitable outcome of the hedonism of the scene. “Yes, she was a child in a toy shop,” he says in Days & Summers, “and it just became too much for her.”

“None of us knew what we were doing with drugs – we were young and stupid,” admits Grace Slick. “We were either having a good time with them, or using them to calm down. When you felt bad, you’d go shoot some heroin or drink some alcohol or whatever. Everybody was doing it. Heroin is really tricky, because you only take a small dose and so then you think: ‘Oh, I’ll have a little bit more.’ But a little bit more will kill you.”

Her death, terribly, was a sign of the times. “That whole rock star thing caught up with her, as it did with a lot of pop idols in the early Seventies,” says Rundgren of a singer who was an early member of what Kurt Cobain’s grief-stricken mother later called “that stupid club” – musicians who were dead at 27. Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison were all that age when they died between 1969 and 1971.

“There was this feeling of invincibility going around,” the producer continues. “Once you’d achieved that stardom, you got giddy. And it was proven several times over that these people weren’t invincible, with Morrison and Hendrix and Joplin all dropping like flies.”

But it was, of course, also an awful family tragedy. When the news came, Laura was in Dallas, where she’d begun graduate school. She was at home alone in her shared apartment. “It was very difficult,” she says now, “to be surrounded by silence when internally I was very empty.”

Michael was at home in Port Arthur. The call came in the middle of the night, and his father woke him in the morning. “He could barely get the words out. He said, ‘Your sister’s dead’, then he had to leave the room, because he was gonna lose it.

“What was really weird was that I wanted to go tell somebody, and have that conversation with my best friend: ‘My sister passed away.’ But he already knew. ‘How did you know?’ ‘It was on the radio.’ That was my first taste that I didn’t have any [private] family thing about this. And my parents were not able to deal with that at all. It was so talked about – it was on the national freaking news!”

In fact, so was Michael. When his parents travelled to California to make the arrangements, they left him at home. “They were afraid to have me part of that scene, which I understand. But they also didn’t realise that Dan Rather was going to call the house. And I’m there, waiting for them to call, so I answer the phone and I’m 17, talking to Dan Rather on the nightly news! We were just unaware of what was going to be transpiring.

“That was a really hard time,” he continues. “My idol was dead. And it was tough. Mostly, if you ever lose a family member, they go away. And your memories are what keep them alive in you. But with this, I’m talking to you 50 years after – it’s crazy, a weird thing. You’ve got your perceptions of Janis, I have mine, and I can’t change everyone else’s.”

Given the cultural lionisation – and the tearing down – of various Sixties and Seventies musical legends in the decades since, it’s remarkable that there’s been no film of the life of Janis Joplin. That’s not for the want of trying, notes Michael. Over the years, multiple actresses have been linked to the role, including Pink, Amy Adams, Michelle Williams and Courtney Love.

“There’s been a lot of people in the talk, and until it happens, it’s only all talk. For a long time I was holding my breath, then I gave up because I started turning blue. Now I’m like, if you want to do it, you better come to me with something real. Until then, it’s just BS. It’s Hollywood, man. I have a drawer full of scripts!”

But nothing that he and Laura thought was up to snuff?

“We didn’t stop anything. We have never said no to anybody. I would love to have had Pink involved. But things just don’t happen – the funding fell through, or whatever. It’s just that kind of stuff. I’m not an a--hole or anything. If they can figure out how to make it happen, we’ll support them, if it’s good.”

For Laura, looking after her sister’s memory – the family have been careful not to overexploit her legacy – “helped me heal a lot. Talking with people, feeling the incredible love they have for her, really helped me get more anchored. In that regard it’s a pleasure to listen and hear what she meant to people.”

Also, she points out, for all the sense of a depressed and doom-laden mythos that’s attended her sister in subsequent years, “the thing that can sometimes be overlooked is: she was so much fun to be around. Janis was a high-energy girl who had an unending curiosity.” Or, as Janis said to Eye magazine in June 1968: “I have at least a thousand people inside of me and I don’t know which is the real me.”

Those qualities are all over the deluxe, coffee-table pages of Janis Joplin: Days & Summers: Scrapbook 1966–68. Immerse yourself in the mind and soul and chaos of Joplin’s too-short life and career, and you understand why her siblings might still want their sister’s story told on screen, but told right.

“There’s been a lot of powerful woman that wanted to portray her,” says Michael, “because Janis is a perfect story in every aspect. It’s like Shakespeare.”

Janis Joplin: Days & Summers: Scrapbook 1966–?68 is available to pre-order now. Info: janisjoplinbook.com