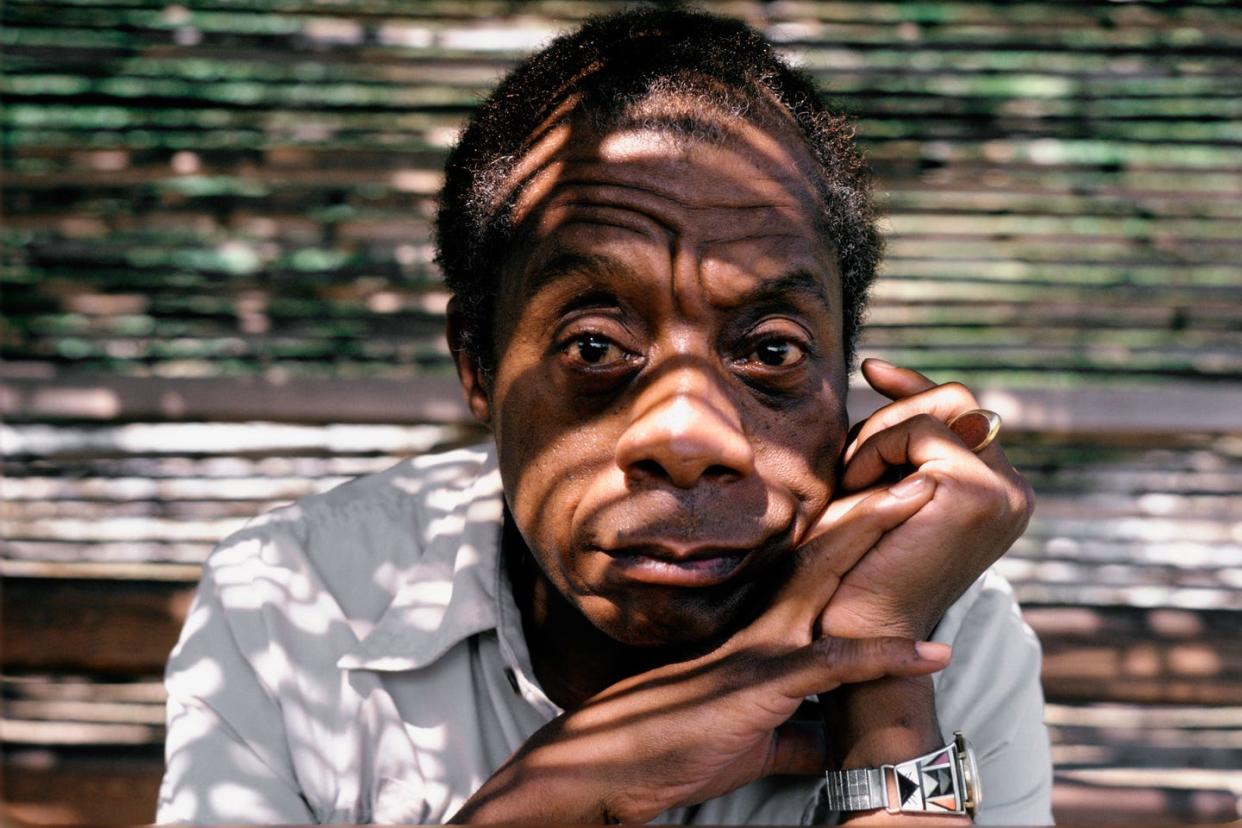

To Us, He Was James Baldwin. To Them, He Was Uncle Jimmy.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

In late 1962, James Baldwin wrote an open letter to his fifteen-year-old nephew, James, that was published in Progressive magazine and later included in The Fire Next Time, his third collection of essays. The oldest of nine children, Baldwin had previously used his family as an inspiration for his semi-autobiographical novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain. On his first reporting trip to the South in the late fifties, he had witnessed the impact of racism on Black children who were subjected to white mobs during the fight for public-school integration. Now, in “A Letter to My Nephew,” he warned little James, his brother Wilmer’s son, that he “could only be destroyed by believing that you really are what the white world calls a nigger.”

Baldwin would educate his young namesake about the costs of being Black in America, and the low expectations that white people would have for his life simply because of the color of his skin. Yet he was also hopeful. “It will be hard,” he told his nephew, “but you come from sturdy, peasant stock, men who picked cotton and dammed rivers and built railroads, and, in the teeth of the most terrifying odds, achieved an unassailable and monumental dignity.”

It’s been more than fifty years since the publication of “A Letter to My Nephew,” and thirty-seven years since Baldwin’s death in 1987, at the age of sixty-three. August 2 marks what would have been his one hundredth birthday. Celebrations are under way in New York, where Baldwin was raised, in Harlem; and in Paris, where he lived off and on for many years. Today, long after its conception during the civil-rights movement, “A Letter to My Nephew” continues to resonate with readers. In a 2015 Atlantic essay, Ta-Nehisi Coates evoked it in his “Letter to My Son.”

In the early nineties, I discovered “A Letter to My Nephew” during a college literature seminar. Around that time, I met Trevor Baldwin, who was then a student at Morehouse College in Atlanta, during a football game in New Orleans. It took me years to learn that he was James Baldwin’s nephew: Wilmer’s son and the younger James’s half brother. By the time I ran into Trevor again many years later, in 2018, I had long wondered about what had happened to his half brother. The murder of George Floyd had forced my own reckoning with the perilous state of Black men in America, and Baldwin’s letter to his nephew became a reminder of what was at stake for my own sons and nephews. Though I lived in a Harlem that was very different from the one Baldwin reconstructed in his novels and essays, I was still confronted daily with the afterlife of slavery, housing and job discrimination, over-policing, and poorly performing schools. We were all Baldwin’s nephews, and his message was as relevant now as it was when he was writing in the middle of the twentieth century.

To his biological nephews, Baldwin was Uncle Jimmy, the childless and unmarried globetrotting writer who, when he came home to New York, brought an infectious laughter, a curiosity about everything, and an enduring love for his family. The Baldwin nephews each discovered their uncle’s prodigious output of novels, essays, plays, and speeches in different ways, and now they’ve each found their own meaning in his legacy. This summer, I spoke with four of them about both the blessing and the responsibility of being stewards of their uncle’s lessons for these times.

On August 2, 1974, at his villa in St. Paul-de-Vence, Baldwin celebrated his fiftieth birthday with friends and family. Thirteen days later, Trevor was born in New York. In a letter dated October 21, 1974, Baldwin apologized to the newborn for his tardiness by not acknowledging his birth sooner. “As you will learn in time, none of your uncles are notorious for their punctuality (neither are any of your aunts) but your Uncle James, being the oldest, has had more time than the others to perfect the Art of Being Late,” Baldwin wrote.

Trevor, who only discovered the letter as an adult while cleaning out his parents’ home, now cherishes it for the blessing that his uncle gave his birth. Whenever he needs a boost, he reads the letter. “You’ll be very good…for all of us; we needed you, more, perhaps, than we guessed, and your father, and I think most of all,” Baldwin told him. “New life prolongs life, and so I thank you for that.”

In 1987, at his Uncle Jimmy’s funeral at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Trevor was the head chorister and sang with the Cathedral School choir. Toni Morrison, Amiri Baraka, and Maya Angelou, who is Trevor’s godmother, gave speeches in the packed church. Then approaching fifteen—the same age his half brother, little James, had been when he received “A Letter to My Nephew”—Trevor was mesmerized by Baraka’s long speech about his late friend, whom he called his “older brother” and an “elegant griot.” Yet Trevor felt out of place and conflicted as he sat in the choir stand watching his weeping grandmother, Berdis Baldwin, the matriarch who’d always brought light to her oldest child’s eyes when he saw her.

“You’re not supposed to have a view of your family at a funeral,” Trevor tells me. “You’re supposed to be in the family.”

In the years before Baldwin’s death, when the family gathered at the four-story converted brownstone the author bought for his mother at 137 Seventy-first Street in Manhattan, Trevor remembers his uncle’s laughter, as well as a speaking voice that contained at once the elegance of a Shakespearean actor and the power of the Black Pentecostal preacher he was as a teenager. Trevor had overheard the adults talking about his Uncle Jimmy, but there were parts of his life and personality that were largely unknown to him. He was a ten-year-old kid on the Cathedral School playground when he learned from a classmate that his Uncle Jimmy was gay. “Your uncle is a faggot,” the classmate told him. “So you’re probably going to be a faggot, too.” It wasn’t the slur that stunned Trevor—he’d heard that word on the playground before. It was learning that his Uncle Jimmy was gay from a stranger.

What Trevor knew about his Uncle Jimmy was mostly this: that he was an established writer. He saw the essay collections and novels on his parents’ bookshelves. When your uncle is a famous writer, especially one who wrote so personally and vividly about his family and race in America, it’s possible to come to know him even better through his work.

Trevor’s serious interest in Baldwin’s oeuvre was instigated by the notorious 1986 Howard Beach hate crime in Brooklyn, where three Black teenagers were attacked by a group of white teenagers. That event (and the release three years later of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing) raised his antennae about race in America, drawing him closer to his Uncle Jimmy. During high school, a couple years after Baldwin’s death, Trevor began reading Black Voices: An Anthology of Afro-American Literature, a pioneering collection of Black writers published in 1968 during the civil-rights movement. The book pointed him toward his uncle’s essays and his contemporaries, such as Baraka and Richard Wright.

For Trevor’s cousin Clarence Harris, a grandson of Baldwin’s oldest sister, Barbara Baldwin, the introduction to his Uncle Jimmy’s work came while he was serving an eighteen-month prison sentence for a white-collar conviction at the Marcy Correctional Facility, a medium-security prison in Upstate New York. The first book he received in the mail from his Aunt Gloria Karefa-Smart was The Cross of Redemption, a collection of Baldwin’s essays, articles, reviews, and interviews, edited by Randall Kenan. His Aunt Gloria, who was for a time her brother’s secretary, is the literary executor of the James Baldwin estate. Harris spent his free time behind bars reading his Uncle Jimmy’s books, and when he was done with them, he would pass them around to other inmates. The Cross of Redemption displays Baldwin’s wide range of interests, from cinema to Black English to boxing to music to the prospects of a Black president to anti-Semitism.

“That book changed my view of the world,” says Harris, who is fifty-six and lives in the Bronx. “My Uncle Jimmy civilized white America for me.”

Harris witnessed the civilizing effect that Baldwin’s essays and speeches could have on people when he shared the book with a fellow inmate who held white-supremacist views. When the man brought the book back to Harris after reading it, he said, “Was your uncle a prophet?” Harris says that after reading The Cross of Redemption, the man became a totally different person, and that his uncle had helped show him his own humanity.

It was “A Letter to My Nephew” that brought Hakim Wilson, a now-fifty-two-year-old Baldwin nephew, closer to his Uncle Jimmy’s work when he read it as a teenager. “I'm sure a lot of Black kids can probably read that and feel like it's something their parents would probably tell them, growing up as a Black kid in America,” Wilson says. “But I felt personally connected to it because I am James Baldwin’s nephew.”

The most popular perception of Baldwin is of a man telling the world the honest truth about racism in America. But his nephews remember their uncle as a man who also enjoyed having fun and showing love and affection for his family. Wilson remembers himself as a nine-year-old sharing the stage with his Uncle Jimmy at an event in New York, where they did a breakdancing routine together called pop locking.

“I was pretty young to try to grasp the essence of what this man meant to the world,” says Wilson, a land surveyor in Los Angeles. “I knew he was a star. But as a kid, it was always just great joy to have him home, because he brought all of us together.”

Another nephew, Daniel Baldwin, has memories of his Uncle Jimmy holding court at Mikell’s, a jazz club on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where his brother David was a bartender.

Over the years, David went everywhere with his older brother, and almost as soon as his son Daniel was born, he began taking him to Baldwin’s home in St. Paul-de-Vence. With his Uncle Jimmy and his parents, Daniel would go to Italy on short excursions to see Yoran Carzac, the French artist who drew the illustrations for Baldwin’s only children’s book, Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood. First published in 1976, the book is about a four-year-old boy named TJ who lives in the crime- and drug-infested Harlem of the seventies. Baldwin, who called Little Man, Little Man “a celebration of the self-esteem of Black children,” wrote it at the urging of another nephew, Tejan “TJ” Karefa-Smart, who was the inspiration for the main character.

For Daniel, Little Man, Little Man was his first encounter with his Uncle Jimmy’s work and fame. “Reading Little Man, Little Man at five or six years old, I realized that my Uncle Jimmy was an important writer,” saysid Daniel, now a fifty-one-year-old sound engineer living in Providence, Rhode Island. Perhaps Daniel’s best education about his Uncle Jimmy came from his father, David, who frequently pontificated about ideas his brother had articulated in speeches or essays.

Baldwin’s own instruction to his nephew was more subtle: He taught Daniel how to play chess when he was about three years old. “We would play checkers together, and then I remember the pieces started looking different, and he started to teach me chess,” Daniel says. “To learn that game was one of the most valuable philosophical lessons of my life. It’s something that you don’t think you use every day, but you do.”

In the summer after Baldwin’s death, in 1988, Daniel and his cousin Trevor spent nearly a month at their uncle’s stone house on a hillside in St. Paul-de-Vence. For the first time, Trevor got to see the place where his uncle had lived and spent his last days. “It was a true coming-of-age summer for us,” he says. “We were treated like princes because Uncle Jimmy’s death was so recent that the village store owners gave us whatever we wanted.”

Nowadays Little James lives in a mental-health-care facility. During his childhood, Trevor saw his older half brother infrequently. He doesn’t share many details about his life, but he visits him often. These nephews are fiercely protective of their Uncle Jimmy’s legacy, as he is fully alive in their hearts and minds. The last of their uncle’s generation will soon pass the torch to them and their other relatives; soon it will be their responsibility to decide what to do with his legacy.

Billy Porter, the actor best known for his Broadway performance as Lola in Kinky Boots, is writing a script based on Baldwin’s life and plans to portray the writer in a biopic. The script will be based on David Leeming’s 1994 book, James Baldwin: A Biography. Leeming, who sold the movie rights to Porter, was a sometime assistant and friend to Baldwin for many years. That being said, at least one Baldwin nephew is deeply concerned about how the flamboyant and openly gay Porter would portray their uncle. “It’s a betrayal for David Leeming to make that decision,” says Clarence Harris. “He knew my uncle better than most people, and he knows that my uncle was not anything like Billy Porter.”

Though Baldwin never shied away from his identity as a gay man—he had male lovers and the theme figures prominently in his novels Giovanni’s Room and Another Country—he resisted the label. In a 1984 interview with The Village Voice editor Richard Goldstein, Baldwin gave perhaps his most detailed thoughts about his place in the gay community. “I was never at home in it,” he said. “Even in my early years in the Village, what I saw of that world absolutely frightened me, bewildered me. I didn’t understand the necessity of all the role playing. And in a way I still don’t.”

But just as Baldwin was very difficult to pin down to any group or philosophy during his lifetime, he continues to defy strict conventions in his afterlife. It’s a Baldwin family ritual, I learned in my interviews with the nephews, to pay close attention (often with a mixture of pride and dismay) to all the ways their Uncle Jimmy is interpreted by academics, journalists, filmmakers, politicians, and activists.

Trevor, who is working on a range of projects related to his uncle’s centennial and legacy, is helping lead the family’s charge to shape the future of Baldwin’s singular place in American letters and popular culture. The family has its own TV and film development plans in the works. But first, for the centennial, Trevor was the executive producer of The Baldwin 100, an eight-episode podcast series from Penguin Random House, which has also issued a box set of the writer’s major novels Go Tell It on the Mountain, Giovanni’s Room, and If Beale Street Could Talk. On August 2, Baldwin’s would-be one hundredth birthday, the family is hosting a celebration at Lincoln Center after events earlier in the day at the New York Public Library and Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which acquired Baldwin’s papers from the family in 2017.

“As a family, we want to be the main equity stakeholders of Uncle Jimmy’s name, image, and likeness to help shape the narrative for the future,” Trevor says. “But we recognize that he doesn’t just belong to us. There is a deep spiritual connection that people have with him. There is something about his persona that has made him almost a biblical and mythical type of figure that’s not limited to his books. This is about us as a family planting the flag to be at the center of this Baldwin universe.”

You Might Also Like