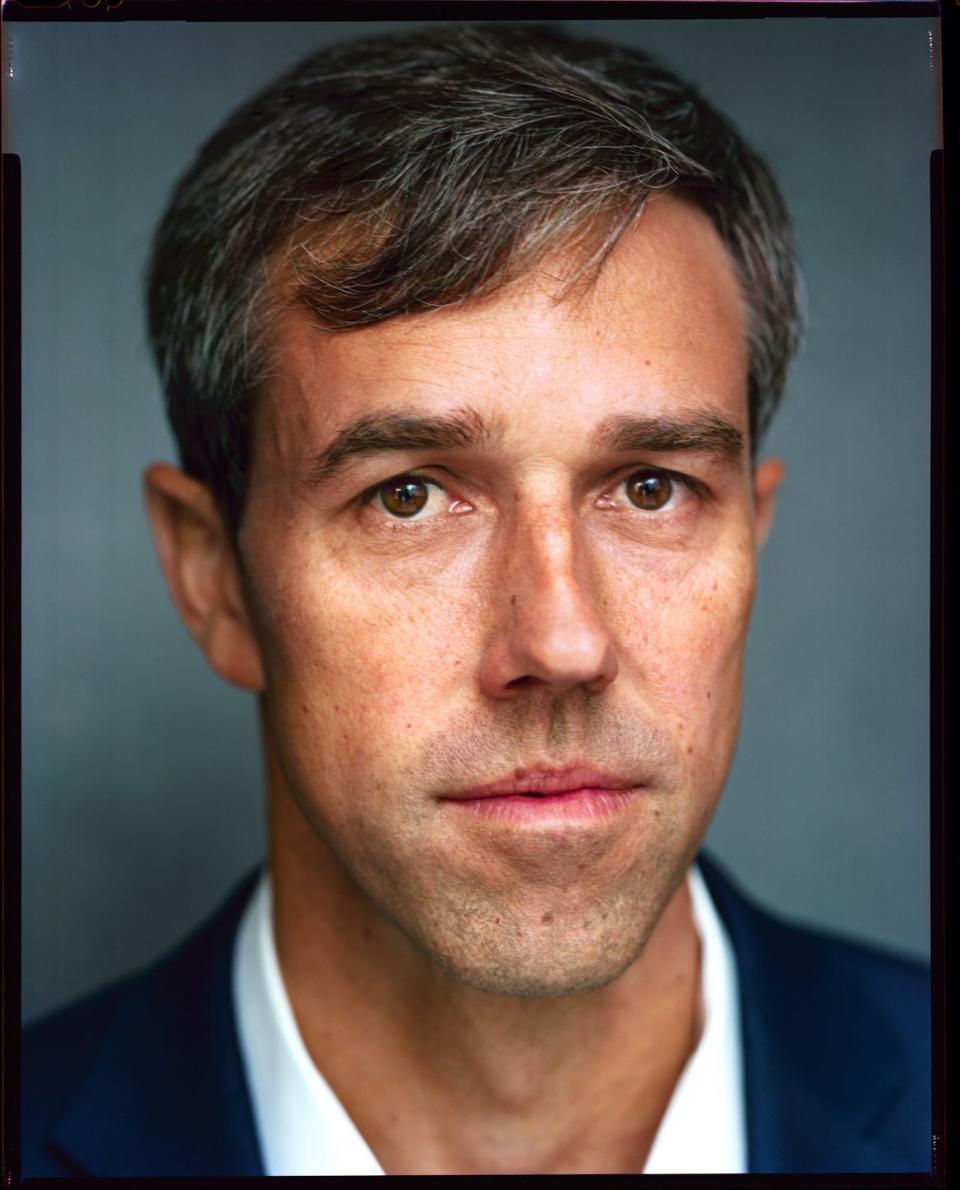

Why So Many People Are Betting on Beto O'Rourke

Just after he was elected to Congress in 2012, Beto O’Rourke was in a bar in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with several other newly elected pals. A woman came up, looked at O’Rourke, and said, “Are you who I think you are?”

He had just won a long-shot race for a House seat that had garnered some national attention, so he said yes, he thought he probably was who she thought he was. She pulled him over to her table to meet her friends. They gave him high-fives and started taking pictures.

“It dawns on me: They don’t think I’m Beto, they think I’m Joe Kennedy, or at least some Kennedy,” O’Rourke says. Finally he confessed, “'I’m not who you think I am. I’m Beto. From El Paso.’ I could just see the thrill go out of their eyes.”

Luckily, the real Joe Kennedy was nearby, so O’Rourke went back to the table and grabbed him to come pose for some photos.

“Beto is often referred to as the best-looking Kennedy in Washington,” says Joe Kennedy, who is now close enough friends with O’Rourke to have borrowed his dress shirt one time when he arrived at an event while covered in coffee stains. “Which wouldn’t be so bad if I weren’t standing right next to him when it happens.”

Six years after that encounter at the bar, O’Rourke is running a U.S. Senate campaign a world away, in Texas-a race that resembles one run by another Kennedy. It’s not just the toothy grin, the tall stature, and the shock of hair swept over his brow. With a disdain for highly paid consultants, a willingness to travel to unexpected places, and an inspiring message for an extraordinarily divided electorate, it’s hard to look at O’Rourke and not think of Bobby Kennedy in 1968.

On a June morning O’Rourke is cruising down a Texas highway, and he is in a hurry. He’s in the midst of a whirlwind campaign week in his bid to unseat the state’s current senator and former presidential candidate Ted Cruz. He’s going well above the speed limit as he sips from a bottle of water, by far the healthiest thing he’ll have all day.

A car swerves in front of him, he slams on the brakes, and his campaign almost ends right there. “Whoa! Fuckers! Sorry,” he says. “This jackass pulled off the side of the road into everyone’s way. Sorry, guys. But we lived.”

It was a near miss, but, as in so much of his life, O’Rourke was lucky. He resumes talking about his unlikely path to a political career that could include one of the more shocking wins of a shock-filled political era.

O’Rourke is currently testing whether the nice guy approach can work in a smashmouth political climate. He’s testing whether the tide in Texas-a state that Democrats have been eyeing for years-has finally seen the kinds of demographic shifts the party has been hoping would lead to victory.

He’s also testing whether the gun control debate can resonate in one of the most heavily armed states in the country. And whether the opposition’s build-the-wall mantra might backfire in the state with the longest border with Mexico. He’s preaching climate change legislation in a state where the economy is dominated by oil and energy companies.

Can a guy who looks like a Kennedy, and often sounds like one, too, win a statewide election in Texas?

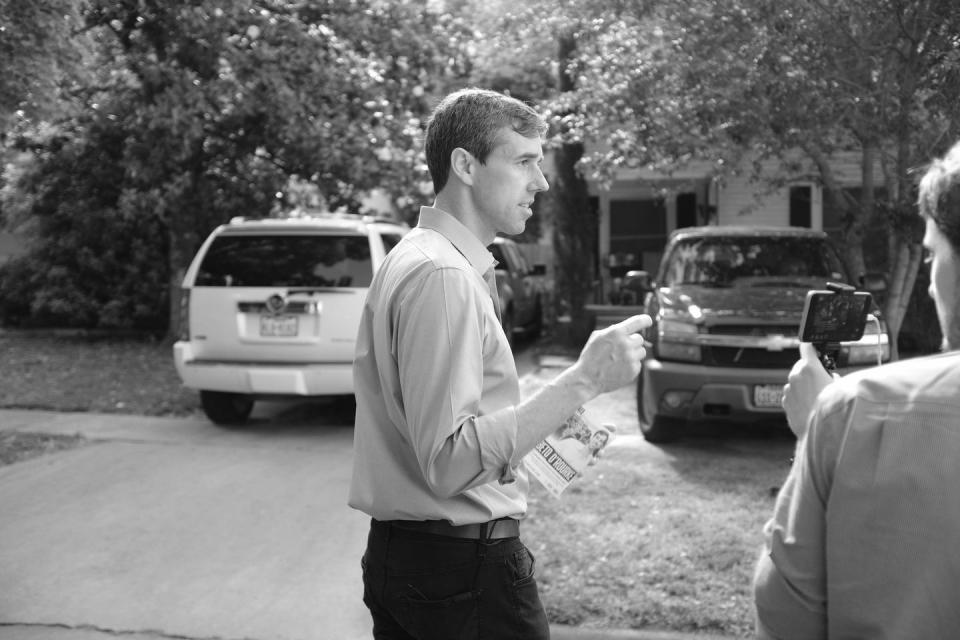

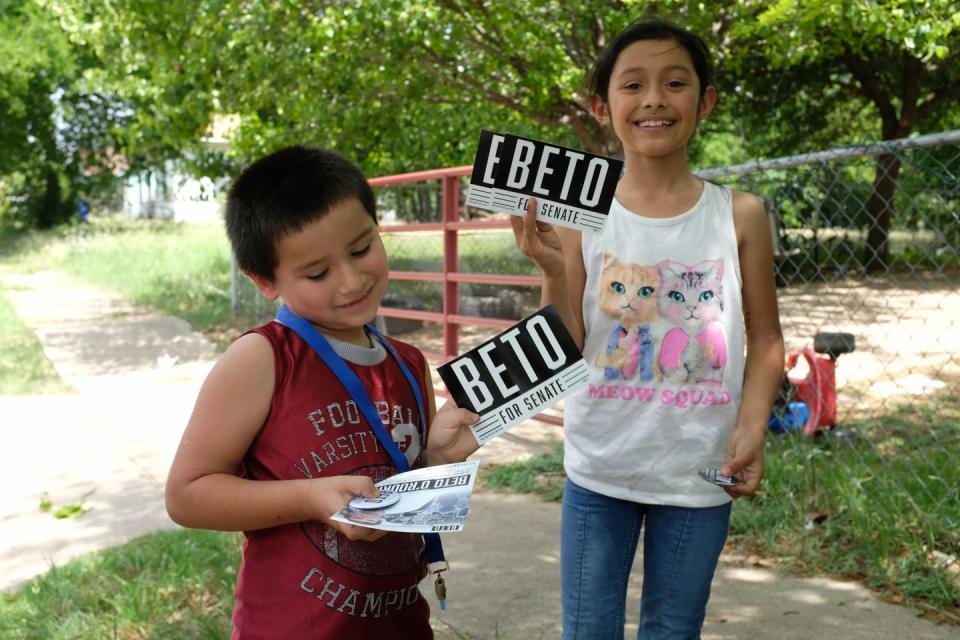

O’Rourke’s campaign approach reflects his own accessible, easygoing nature. He has been to all of Texas’s 254 counties-including ones no Democratic candidate has seriously contested in decades-an achievement that was celebrated with a cake that contained an image of O’Rourke’s face in the icing. If he can meet every person, knock on every door, he thinks he can win-even though grassroots campaigns in a state of 28 million people don’t often work.

He has also captured attention at the national level. A recent Manhattan fundraiser for O’Rourke drew actors Paul Rudd, Michael Urie, and Stephanie March; legendary civil rights activist David Mixner; Elton John AIDS Foundation honcho Scott Campbell; and Ralph Lauren global brand president William Li, among others.

“I think and I hope that in a post-Trump world more people will show up at the polls,” said March, who is a fifth-generation Texan on both sides of her family. “I think Beto would be galvanizing anyway. It’s so joyful to choose a candidate not because he’s not as bad as the other one but because he’s really great.”

On a hot summer day not long ago, O’Rourke approached the man with the lawnmower, asking for his vote. He talked to the women about to have a garage sale, asking for theirs. He talked to a couple who had just arrived with a carful of groceries and asked about their concerns-then offered to help carry the groceries inside. “This is as direct as democracy gets,” he says. “If I could do this all day, every day, I would.”

As he stood on one porch, a prospective voter seemed to notice the sweat accumulating on his face and throughout his shirt, so she offered him a popsicle. His face lit up. “I’ll take a popsicle!” After she returned with a choice of colors, he got to work on the pink one. “I’ve been block walking since 2005. This is the first time I’ve been offered a popsicle. I’m so excited.”

He jumped back into the white Dodge Grand Caravan, driving it himself as his deputy campaign manager in the back seat offered directions, sometimes in English and sometimes in Spanish. The engine roared. Beto O’Rourke was in a hurry.

Robert Francis O’Rourke is a fourth-generation Irish-American. He was born in 1972 in El Paso, a city to which he has returned again and again-a place that, in the far western corner of Texas, where the state borders Mexico and New Mexico, defines much of his political identity. “It’s the most amazing place, visually,” he says. “The people and the connection, the binational character of the community.”

His mother ran a high-end furniture store and made sure the family had a home-cooked meal every night. His father was a county judge and the state chairman of Jesse Jackson’s presidential campaign in 1984.

For as long as he can remember he has been called Beto-a nickname for many of the Roberts, Gilberts, and Alberts growing up in El Paso. Early in the current campaign Ted Cruz, whose given name is Rafael, took out an ad suggesting that Beto was using the name as a way to appeal to Hispanic voters.

O’Rourke finds this amusing. He recalls a red terry cloth shirt with Beto stitched into it that he wore in childhood. “It’s probably why I got beat up so much,” he jokes. “There were absolutely times in my life when I tried to get people to call me Robert,” he says. “I remember in sixth grade, the best teacher I ever had, who really took a liking to me and believed in me, said, ‘I’m going to call you Robert because Beto is a nickname-but not a big, strong nickname. I want you to be a Robert in life.’ ”

When he went off to college, at Columbia University, he introduced himself as Robert O’Rourke. “I didn’t want to explain what Beto is and how to pronounce it,” he says. “I wanted to fit in, and Beto doesn’t fit in… There’s also a disconnect, right? There’s this tall white guy, and he’s Beto.” But eventually he realized that he just wasn’t a Robert. “Trying to grow up, quote-unquote, and have this serious name just wasn’t me and where I’m from,” he says. “At some point I just got comfortable with who I am.”

As a teenager O’Rourke found a home in El Paso’s burgeoning punk rock scene. “For me it was about finding a community as a little bit of a misfit,” he says. He and a group of friends formed a band called Foss. They started a record label and booked tours, traveling the country and parts of Canada during his summers off from Columbia, where he majored in English and captained the crew team.

O’Rourke wasn’t the best musician in the band, he says, but he was the best roadie. “There was a macho dynamic that I loved,” he says. “Who could put the greatest number of hours in the driver’s seat in that station wagon as we were crisscrossing the country? Who could carry all the stuff? Without being corny, there is something about what we’re doing now that really reminds me of that at its best,” he says. “A bunch of friends in a van…and we’ve got all our gear in here, and we’re just going from one town to the next, both telling our story and listening to and learning from other people’s stories.”

After a couple of years in New York (during which he worked at an art delivery company called Hedley’s Humpers and at some internet startups), in 1998 O’Rourke bought a truck on Long Island for $1,000, drove back home to El Paso, and started his own business.

He married Amy Hoover Sanders about 10 months after they met on a blind date-an evening on which they crossed the border and went to a bar called the Kentucky Club that claims to have invented the margarita. A year later they had the first of three kids, Ulysses (named in honor of a favorite book, the Odyssey), who is now 11. Then came Molly, 10, and Henry, 7. They live in El Paso, a few blocks from where O’Rourke grew up, and his kids are attending the same public schools he did.

It was just a few weeks after the wedding that he won a campaign for city council, defeating a two-term Democratic incumbent to become one of the youngest members in the council’s history. He did this a few years after his father-an avid cyclist who once rode a white recumbent bike across the country-was killed when a car struck him from behind during an early morning ride.

“At that time I was not gregarious,” O’Rourke says. “I was not like my dad at all. I was very shy, I lacked confidence-and you’ve just got to knock on doors. Some people slam them in your face. Some you just woke up from a nap. Some are so glad you came and have never had someone knock on their door before.”

When he decided to run for Congress in 2012, O’Rourke again was the underdog. He was challenging eight-term Democratic congressman Silvestre Reyes, who had been endorsed by both Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. (Texas’s 16th District is predominantly Democratic, so the winner of the party’s nomination is likely to win the general election.)

During the race, Reyes’s supporters poked fun at the name Beto and raised questions about his arrest record, running an ad with a mug shot of O’Rourke and highlighting a 1995 charge for attempted forcible entry and a 1998 drunken driving charge. (O’Rourke was not convicted in either case; regarding the forcible entry, he has said that he tripped an alarm while jumping a fence at the University of Texas at El Paso.)

In the campaign, O’Rourke knocked on 16,000 doors and wore through at least two pairs of shoes. He had no paid staff and couldn’t afford the glossy flyers and slick TV ads-one of which ran during the Super Bowl-that Reyes deployed. Still, he won.

It was a preview of how he would run his Senate race. He has a small staff, with no paid speechwriter or pollster. He has eschewed the large donations from political action committees that can quickly fill a campaign account, and still he has outraised Cruz during most fundraising cycles. It has been three decades since a Democrat from Texas was elected to the U.S. Senate. No one from El Paso-a place so remote from the rest of Texas it’s in a different time zone-has ever won a statewide race.

Every few years a candidate comes up, attracts attention, and then loses by double digits. But for a man who has spent his political career battling the odds, the hurdles don’t seem to matter. Donald Trump’s victory-and the anti-immigrant rhetoric, the plan to build a wall-became a motivation for O’Rourke. “It was very much an emotional decision, less a rational and logical one, and definitely not political-as funny as that sounds,” he says. “It was just, ‘We’ve got to do something’… So, as a family, we came to understand that for the better part of two years we were not going to see one another.”

The atmosphere surrounding his campaign has only gotten more intense since he announced his run. Texas has become the focus of national media attention because of the Trump administration’s policies on families who cross the border illegally-and O’Rourke, who has challenged Cruz to six debates, including two in Spanish, feels that this is a defining moment.

“This is not America,” he said in June while standing outside a facility housing children whom the Trump administration had taken from their parents. “This is not us. This is not what we do.”

Shortly after making the decision to run, O’Rourke called his longtime friend Steve Ortega, a lawyer who served with him on the El Paso city council years ago. “I thought, ‘This guy has a 1 percent chance,’” Ortega says. “I discouraged him. But a month later it was, ‘Oh, maybe he has a 5 percent chance.’ And now I’m like, ‘There’s a really good chance he’s going to win this.’ ”

O’Rourke’s campaign pins bear a striking resemblance to ones Bobby Kennedy used in his 1968 presidential campaign. And his campaign stops include speaking at the same hotel in Fort Worth where President John F. Kennedy delivered some of his last remarks before he was shot in Dallas.

Like that of the Kennedys, O’Rourke’s oratory is often focused on appealing to the hopefulness of the electorate. His brand is not a polarizing one, it’s one of toothy grins, self-deprecating jokes, and uplifting rhetoric. It’s a message that can seem out of place in the current era. He almost never mentions Donald Trump (though he has said Trump is not fit to serve) or even Cruz.

“That doesn’t fire me up or turn me on or motivate me. It’s not where the energy is,” he says. The country is yearning for something more optimistic, he believes. “It’s why JFK and RFK-60 and 50 years later, respectively-are still inspiring to us. Bobby Kennedy especially, bringing everybody in and reaching everyone. There was something punk rock about Bobby Kennedy not going where the pollsters said or where consultants said. He was unmoored from what was safe or easy.”

Inside a dimly lit ballroom on a late spring evening, some 350 Democrats in a heavily Republican area north of Dallas were gathered for an annual dinner, and they were dressed for the occasion. Some wore black tie. Women were in ball gowns. Wine, beer, and elaborately decorated cupcakes were on the menu.

“No, he’s not a Kennedy,” Elena Hernandez said by way of bringing O’Rourke to the podium. “He just looks like one and acts like one.”

O’Rourke is rarely downbeat, but on this night he was particularly upbeat. His arm motions are often aggressive-he jabs with his fingers, waving his hands like a conductor-to punctuate his staccato speaking cadence. On this night he was even more frenetic than usual.

He went through the things he loves about his hometown: the multicultural flavor of the city; that El Paso shares so much with Ciudad Juárez, the Mexican city across the border; the way the Rio Grande, in his view, links the two cities rather than separating them. “We are the Ellis Island for much of the Americas-or maybe, better put, Ellis Island is the El Segundo, the El Paso, for the rest of the world.”

Although he owns guns and was taught to shoot them by his uncle, a sheriff’s deputy, he proudly boasted, “I’m the original co-sponsor of an assault weapons ban. I do not believe that weapons of war designed for the sole purpose of killing people as effectively, efficiently, in as great a number as possible belong in our streets, in our schools, in our concerts, in our churches-in our lives.” The crowd rose to its feet.

O’Rourke became more impassioned when talking about immigration, saying that the United States has become inhospitable to refugees and immigrants-ripping apart families and deporting young children. “We will be judged,” he said. “There will be an accounting, there will be a reckoning sooner or later. It will either come from ourselves and our own conscience or it will come from our kids when they ask that inconvenient question: ‘What were you doing when they turned those kids back from the border?’ ”

He compared the decision the country is making right now to one it made in 1939, when it refused to allow the St. Louis, a German transatlantic liner, to dock, denying refuge to more than 900 passengers, many of them Jewish. “This country averted its gaze,” O’Rourke said. “Turned its eyes, turned its back. And that ship had to go all the way back to Europe, where more than 250 of those passengers, including kids, were slaughtered in the Holocaust. You ask yourself what you would have done if you were there in 1939. Ask yourself what you’re doing tonight, in 2018.”

As O’Rourke left the stage, the evening’s master of ceremonies, Yolanda Perez, took the microphone. “I have wondered what it felt like to grow up during the JFK and MLK era,” she said. “Tonight I understand.”

On most mornings Beto O’Rourke is up by around 6 a.m., ready to go for a run. “We’ve gone on trips with him before. There’s not a lot of hanging out. It’s all, ‘Let’s go check this out’ and ‘Let’s go here.’ There’s constant, constant movement,” says Raymond Telles, a longtime friend of O’Rourke’s. “For a lot of us, a Sunday afternoon sitting on the couch is pretty inviting. I don’t know that he could do that. I certainly have never seen him do it.”

On one of the few Sundays O’Rourke has taken off this year, Easter Sunday, he took his family camping. On another Sunday this summer he was far from his family, inside a ballroom in Fort Worth talking to a group of Democratic women running for office throughout the state.

“I just want to be myself to the degree I can,” he told the group. “Sometimes there’s a downside to that. I have promised my family, my team, that we’re going to stop dropping the f-bombs.” Two minutes later he dropped the f-bomb.

O’Rourke is far from scripted. He doesn’t use notes when he delivers a speech. A large portion of his campaign has been accessible unvarnished via Facebook’s livestreaming service. His communications director, Chris Evans, is almost always trailing him with an iPhone, ready to go live. O’Rourke has been streamed getting a haircut, doing his laundry, and talking to his wife. “Sometimes I share too much, or I’m sharing the wrong way,” he told the group that morning. “I’ll kick myself. But I’ll take that over scripted and polished.”

After that he posed for a few photos and then left. He grabbed an apple and walked down the escalator and into the Grand Caravan, off to the next stop. As usual, he was in a hurry.

Portrait by Alexei Hay; Photographs from the campaign trail in Texas by Charlie Gross.

Charlie Gross is a Brooklyn-based photographer. Follow him on Instagram and see more of his experiences on the campaign trail with O'Rourke on Esquire.com.

This story appears in the September 2018 issue of Town & Country.

('You Might Also Like',)