Disney's 'Beauty and the Beast' Is Much Less Scandalous Than the Original Novel

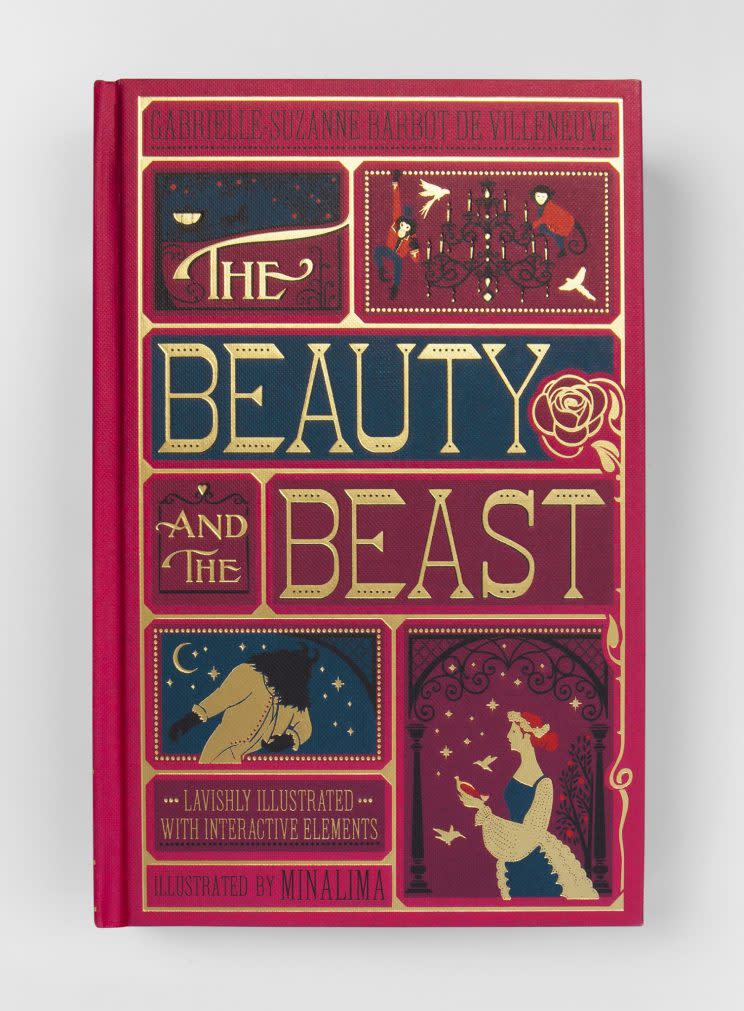

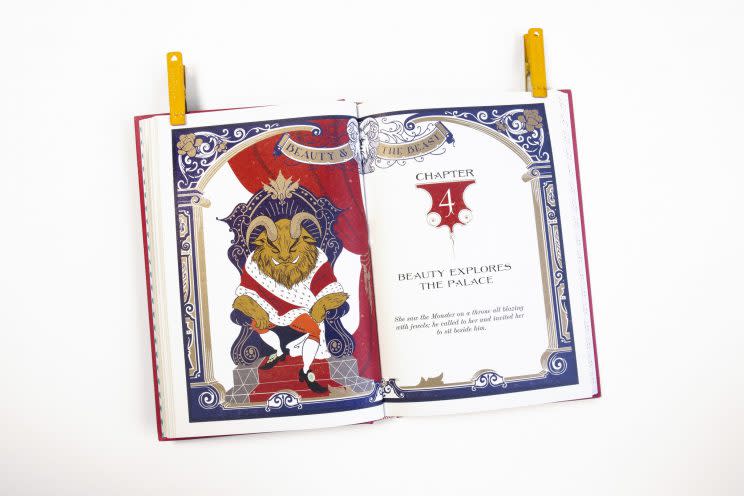

Mrs. Potts sings that Beauty and the the Beast is a “tale as old as time.” But it’s not quite as old as fans might imagine. While similar folktales have been kicking around for thousands of years, the story that most readers know comes directly from a novel by French author Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve, first published in 1740. La Belle et la Bête inspired both the 1991 Disney film and the 2017 remake, which pays homage to the original writer by naming Belle’s village “Villeneuve.” As always, Disney has taken some major liberties with the source material — which is for the best, as Villeneuve’s story goes in some pretty twisted directions. I took a look at the original novel (specifically this gorgeous new illustrated edition from MinaLima) to see which parts of Beauty and the Beast’s story survived intact, and which details (including some very un-Disney incest and seduction subplots) have fallen by the wayside over the past two-and-half centuries.

The Disney animated film takes all of its basic story elements from the novel: A virtuous village girl (Beauty, translated literally into the name “Belle” by Disney) agrees to become a prisoner in a castle owned by the mysterious Beast, in exchange for the Beast setting her father free. Over time, she sees past the Beast’s looks, and they fall in love, thus breaking the spell that turned him into a hideous creature and restoring him to his former appearance as a human prince. The new film borrows a few additional elements from the book — for example, Belle sets the plot in motion when she asks her father to bring her a rose, and he angers the Beast by attempting to pluck it from the castle garden.

While the transformation of the prince’s servants into household objects was a Disney innovation, the castle in the original story is enchanted in its own delightful way. When Beauty moves in, a troupe of performing monkeys and a chorus of talking parrots become her servants. Food, clothing, and jewels are magically provided for her. She has her pick of books from the castle’s library (an idea that Disney, obviously, embraced). Best of all, one of the rooms in the palace has six windows that give Beauty front-row seats to various live events around the world — a comic play, an opera, a society party, even a revolution — like a lush 18th century version of cable television.

Generally speaking, Beauty’s imprisonment is quite pleasant. Sure, she doesn’t get to go home, but in the book she has five jealous sisters who hate her, so that doesn’t seem like much of a hardship. As for the Beast (who is described as “a horrible creature” with “a trunk resembling an elephant’s”), he shows up just once a day to ask for Beauty’s hand in marriage, which she declines. However — and here’s a major difference from the Disney story — the Beast in his handsome-prince form visits Beauty in her dreams every night. He doesn’t explain that he’s actually the Beast, and Beauty doesn’t connect the dots, in spite of his many cryptic statements about how appearances aren’t everything. But she does fall hopelessly in love with him, and ironically, won’t consider the Beast’s marriage proposal mainly because her heart belongs to the dream prince.

Of course, Beauty does have a change of heart, though it’s more about the politics of marriage than true love. The Beast allows her a brief visit home, during which time Beauty’s father — a broke merchant who has been made rich again, thanks to gifts from the Beast — urges her to consider his nightly proposal. “It is much better to have an amiable husband than one whose only recommendation is a handsome person,” Beauty’s father tells her. “How many girls are compelled to marry rich brutes, much more brutish than the Beast, who is only one in form, and not in his feelings or his actions?” In other words: A girl could do worse!

When she returns to the castle, Beauty finds that the Beast has fallen sick, and her concern makes her realize that she does feel affection for her captor. She says “yes” to his proposal, the sky magically lights up with “twenty thousand fireworks, which continued rising for three hours,” and Beauty prepares to say goodbye to her prince. But the prince vanishes from her dreams, and when she awakens the next morning, the transformed Beast is lying beside her.

Watch a scene from the new ‘Beauty and the Beast’:

And that’s about where the Disney version ends. But it’s only half the book. For the remaining four chapters, Villeneuve delves into the extremely convoluted backstory of the Beast’s enchantment. As it turns out, the prince in the novel wasn’t cursed as punishment for his own sins; the spell was cast by an evil fairy who essentially kidnapped the prince as a boy, then tried to seduce him as a youth. When he rejected her advances, she transformed him into the Beast. However, a good fairy took pity on the prince, and created the provision that love could reverse the spell. The good fairy also secretly arranged for Beauty and the Beast to meet, as if by chance, through elaborate, years-long manipulation of their families. For example, the good fairy brought Beauty to her merchant father for adoption, in order to disguise Beauty’s true parentage as the daughter of a king and a fairy.

Which leads us to the book’s most shocking twist: Beauty and the Beast are first cousins. Beauty is revealed to be the secret daughter of the King of the Fortunate Island, who is the brother of the Queen, the prince’s widowed mother. By the conventions of 18th-century Europe, this relationship makes Beauty and the Prince a perfect match: They come from the same aristocratic class, and when they marry, their respective kingdoms will remain in the family. By modern conventions, however, it’s much easier to accept that Beauty falls in love with a hairy elephant than it is to accept that she and the Prince are pretty closely related.

There’s one more significant detail that Disney changed, something that seems small, but actually makes a world of difference. In the novel, the Prince is forbidden from showing his true self to Beauty. Under penalty of death from the evil fairy, he must pretend that he is “coarse and stupid” as well as ugly, and not try to win over his captive with words or gestures of love. This means that when Beauty falls for him, she’s doing so purely out of gratitude for his kindness and generosity. Disney’s version — that she gets to know the Beast, and senses in him a soulmate — is much more romantic.

Furthermore, by making Beauty a secret member of the royal family, Villeneuve’s book misses a large part of the Disney story’s appeal: The idea that a humble girl from a tiny village could transform the life of a powerful prince simply by loving him. Fun as it is to read all the scandalous fairy intrigue in La Belle et la Bête, the Disney version makes for a much simpler, and more satisfying, happily-ever-after.

Watch composer Alan Menken preview some of the new songs:

Read more: