Hail! Hail! Chuck Berry: Remembering a Rock ’n’ Roll Legend

While there are very few instances where one person might be credited for spawning an entire genre of music, Chuck Berry and rock ’n’ roll are about as close as these things ever get.

In that great big, unimaginable Rock ’N’ Roll Family Tree that would be impossible for famed U.K. rock chronicler Pete Frame to draw without an infinite supply of pen, paper, and hands, you can just imagine Berry — who died Saturday at age 90 — at the very top, with downward tributaries leading to the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Beach Boys, among many others. And yes, those three bands would have their own enormous share of musical descendants beneath them, but always, inescapably, Chuck would be perched at the apex.

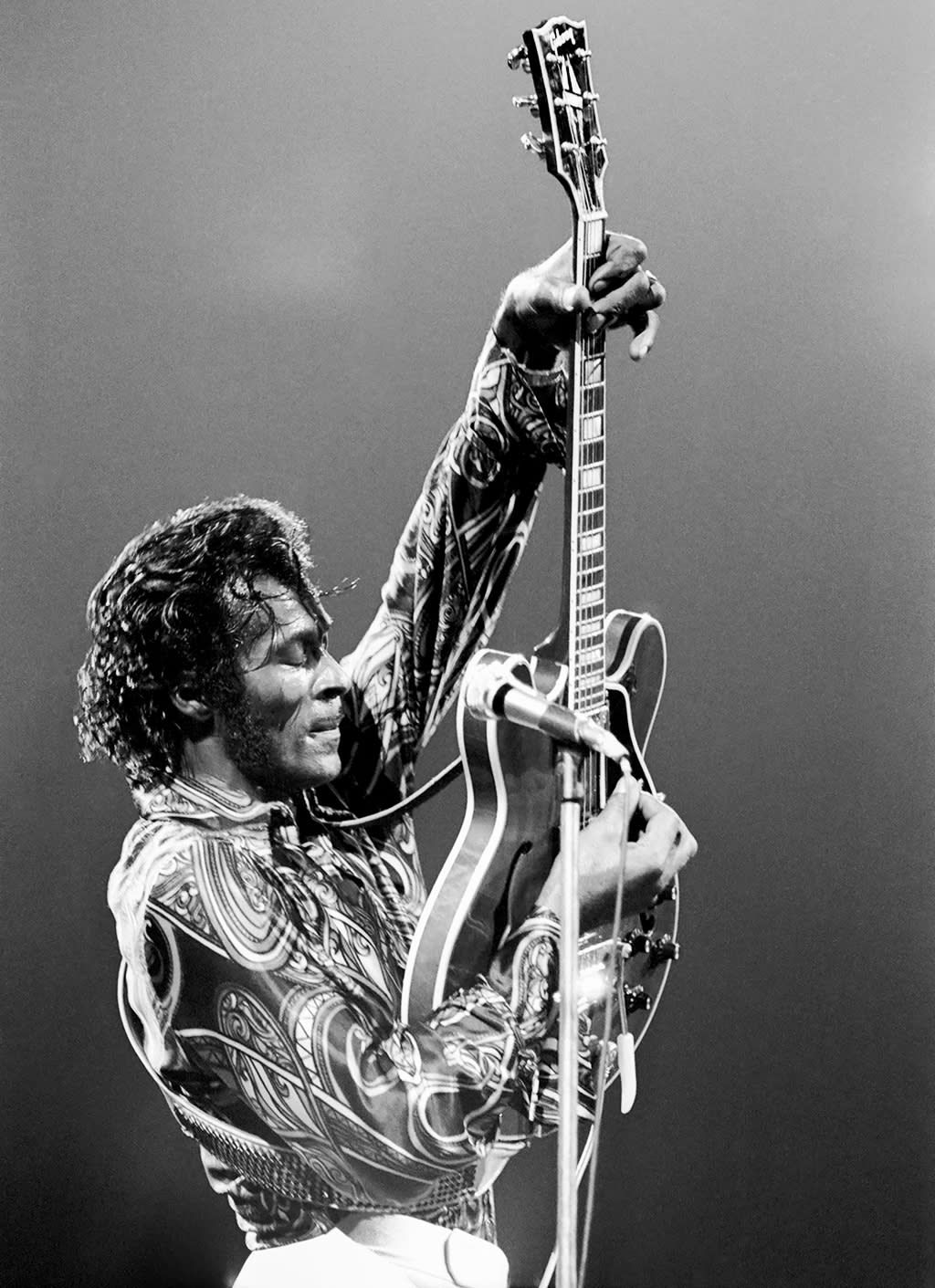

Gallery: Chuck Berry’s Life in Photos

The history is well known. The Beatles covered Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven”; the Stones’ very first single was a version of Berry’s “Come On”; and the Beach Boys’ “Surfin’ U.S.A.” was Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen” bearing brand-new, even more topical lyrics.

All of this came in one year, mind you — 1963. And an entire generation of budding rock ’n’ rollers then danced, sang, and in many cases played their own instruments alongside those songs, those bands, and that irresistible, rhythmic beat. The clever words, the inimitable guitar chords and licks, and the unmistakable attitude that powered those songs came from Berry, and that’s never changed.

Related: Rolling Stones Pay Tribute to Chuck Berry: ‘Your Music Is Engraved Inside Us Forever’

But it didn’t start from scratch. There was a wonderful continuity in what came before with Berry — the interaction of players and figures of another generation making it all happen. In the mid-’50s, Chuck Berry spent his days as a beautician and his nights as a musician. He was looking for career advice, and in 1955 he got it from no less than blues titan Muddy Waters. Waters put Berry in contact with the legendary Leonard Chess, owner of Chess Records, who listened to Berry’s demo tape, heard the track “Ida Red,” and suggested he change its name to “Maybellene.” Berry did, Chess signed him, and… bang.

The songs that followed are almost laughably familiar — iconic expressions in our contemporary culture. Consider the following songs, all Berry’s, and tell me if every single one might not plausibly be a teen movie title: “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Too Much Monkey Business,” “You Can’t Catch Me,” “Rock and Roll Music,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “Beautiful Delilah,” “Almost Grown,” “Back in the U.S.A.,” “No Particular Place to Go,” “You Never Can Tell,” “Promised Land,” and the absolute titular peak: “Let It Rock.” Staggering, actually.

Related: Celebrities Pay Tribute to Chuck Berry

And then there’s Chuck Berry the Guitar Player. He had a pioneering look when he played — do a Web search for “duck walk” when you have a moment — but much more importantly, he had a sound. He is one of a handful of accomplished players/stylists that can recognized by a minimal series of simple notes, who is so integral to rock ’n’ roll that the term “Chuck Berry riff” is understandable to generations of players around the world. If you want a laugh, check out guitarist Chris Spedding’s remarkable “Guitar Jamboree” from 1975, which concisely nails Berry’s unique approach, among others, and has yet to be topped by any other player for its deliberate, joyful guitar mimicry.

And if we’re talking about family trees and cultural impact, it would foolish to ignore that pivotal scene in 1985’s Back to the Future in which Michael J. Fox dazzles a roomful of 1955 teens with an advance peek of “Johnny B. Goode” and blows some minds well before their time. It was the highest-grossing film of 1985, and you (and everybody else) probably saw it.

Yet the grittiness of rock ’n’ roll isn’t always evident in film performances by people like Michael J. Fox. Much of what makes for the most exciting parts of the music and the culture are those things that aren’t squeaky clean — that sometimes are maybe a little misdirected, a little wrong, or even a little (but not a lot) illegal. In the ’60s or later, that might’ve meant the Rolling Stones being fined for public urination or Paul McCartney’s 1980 arrest for bringing marijuana into Japan. But in the ’50s — particularly for a young black man — the law was the law, and it was always serious business.

Chuck Berry had a significant number of run-ins with the law throughout his life, included being sent to juvenile hall in 1944 for armed robbery, and more significantly, being convicted in 1959 of violating the Mann Act with a 14-year-old he’d transported across state lines. For that he was fined, he appealed, and appealed again, but ultimately spent a year and a half in prison. Twenty years later, he would spend 100 days in jail for tax evasion. And in 1990, he was sued by a number of women for allegedly illegally filming them via a video camera installed in the restroom of a Missouri restaurant he owned; eventually a class action settlement ended the matter, though Berry pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges, was fined, and given a suspended jail sentence. And his career continued, as it always did. Because Chuck Berry was always visible. He was always… there.

You can see him in his prime in films like Rock, Rock, Rock (1956), Mister Rock and Roll (1957), Go, Johnny, Go (1959), and the classic jazz documentary Jazz on a Summer’s Day (1960). He made an inspiring appearance in the highly regarded 1965 film The T.A.M.I. Show. He was a captivating physical presence, with a knowing smirk that was not only unprecedented, it telegraphed to a coming generation of rock ’n’ rollers that all the really cool performers would want to show off knowing smirks whenever they could.

And of course, there was that 1987 career tribute, Taylor Hackford’s memorable Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll, a documentary that celebrated the man’s 60th birthday, was filled with behind-the-scenes gossip (paging Keith Richards), is still talked about, and very much spelled out what made Chuck Berry unlike any performer on this earth.

There are those aspects of Chuck Berry that cannot help but linger: That he was money-centric, that he cared more about getting paid than putting on a good show, that he would come to your town, hire a local band to back him, and never tell them what song he intended to play next. That he was driven by devilish emotions that few saw, but those who did never forgot. But what will also linger is his fabulous music, which is miraculously preserved thanks to the perseverance of his various labels. You can hear his best stuff, on Chess, via a number of boxed sets, and even his later material on Mercury — including a fab psychedelic Fillmore set with the Steve Miller Blues Band — which still sounds great. And there’s also a new album, Chuck, his first since 1979, coming soon on Dualtone Records and undoubtedly worth a final, knowing listen.

It is mildly ironic that Chuck Berry’s greatest chart successes came via projects that were by no means essential: His dreary, extended “My Ding-a-Ling” of 1972 was his biggest single ever, and his only top 10 album was the same year’s The London Chuck Berry Sessions, which featured him with a second-string cast of Brit musicians and was mostly a snore. But charts don’t mean anything in the long run. Cultural impact does. There has never been anyone like him, and there never will be again.

Just say his name, and nothing else, and people will know what you mean.