AI deepfakes are part of the 2024 election. Will the federal government regulate them?

Days before New Hampshire's Jan. 23 primary, a robocall sounding a lot like President Joe Biden went out to voters and urged them to stay home from the polls.

"Voting this Tuesday only enables Republicans in their quest to elect Donald Trump again," said the voice. An operative working for Rep. Dean Phillips, D-Minn., a long-shot Biden opponent, later told NBC News he commissioned the ad himself without the campaign's awareness.

On the Republican side, Donald Trump’s campaign posted an audio clip that made it seem as though Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis was speaking to Adolf Hitler, and the DeSantis campaign posted a picture that made it look like Trump was hugging Anthony Fauci.

This use of AI goes beyond the usual campaign dishonesty to actual fabrication. You might assume that is illegal, but the federal agency that oversees elections has yet to take regulatory action on so-called deepfakes.

The head of the Federal Election Commission, or FEC, said he expects a resolution of the issue "later this year," leaving the possibility that this misinformation will be unregulated during the bulk of the 2024 election.

Good-government advocates worry that will allow deepfakes to show voters a candidate doing something they never did.

“You could imagine a candidate being shown drunken or falling down or embracing a criminal or kissing an adversary,” said Robert Weissman, the president of Public Citizen, a nonprofit that is seeking the new rule from the Federal Election Commission. “It’s very hard for the impacted candidate to refute what appears to be authentic content.”

Fake or fact? 2024 is shaping up to be the first AI election.

Group asks Federal Election Commission to ban deepfakes

FEC regulations already ban candidates and their campaign agents from fraudulently misrepresenting themselves as part of an opponent’s campaign in a way that damages the opponent. Public Citizen asked the FEC to clarify that using artificial intelligence to put words in an opponent’s mouth counts as that type of misrepresentation.

It’s the advocacy group's second attempt, after the FEC declined to act on Public Citizen’s first petition in June, which the commissioners rejected in a deadlocked vote, where the three Republican commissioners voted against moving forward with seeking public comments and the three Democratic commissioners voted in favor.

Now, since commissioners voted 6-0 in August to move forward on Public Citizen's second attempt, dozens of organizations, members of the public, and Democrats in Congress have submitted comments in support of the proposal. But Weissman said the FEC is moving too slowly, and the rulemaking process is unlikely to be done before Nov. 5.

“A properly functioning FEC would’ve proactively moved to address this issue long ago,” Weissman said. “They did not.”

He said the agency “shouldn’t be dragged kicking and screaming.”

Sean Cooksey, the FEC chairman, hit back at Weissman’s comments.

“Public Citizen’s statement is typically long on outrage and short on substance,” Cooksey wrote in a statement he sent to USA TODAY. “Any suggestion that the FEC is not doing its job on the pending AI rulemaking petition is simply false. The Commission will continue to work through the regulatory review process, and I expect it will resolve the petition later this year.”

The FEC enforces its regulations on a case-by-case basis, and usually takes them up cases in response to complaints, according to spokesperson Judith Ingram.

The FEC's enforcement powers are civil, so it generally imposes fines, but deadlocked party-line votes like the one in June are common, and have meant certain gray areas of the law are not enforced.

"The FEC enforcement record is miserable, and if they adopt this rule, we would hope that they would be less miserable on enforcement of this," Weissman said.

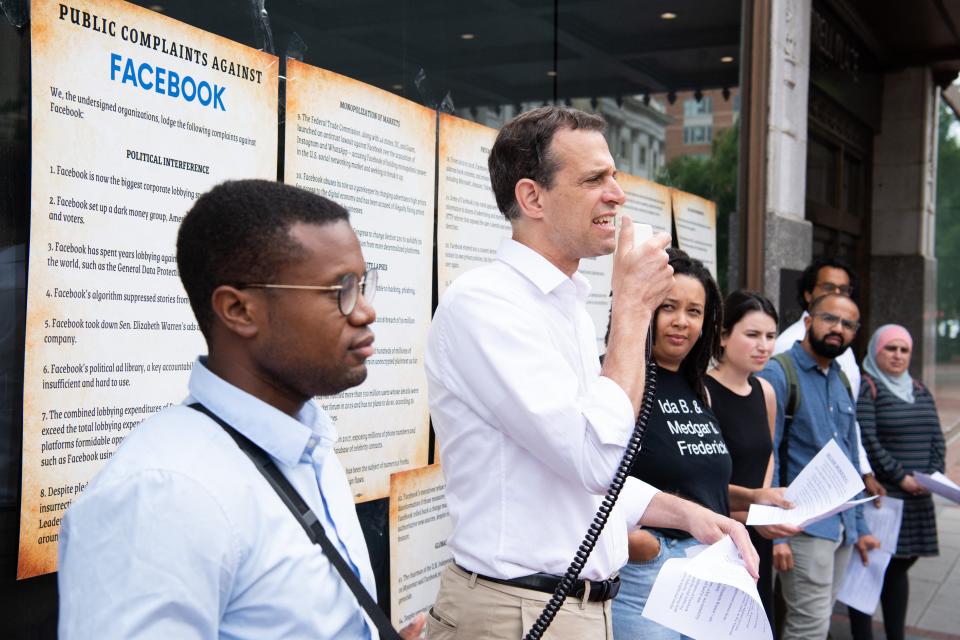

Fake robocalls. Doctored videos. Why Facebook is being urged to fix its election problem.

AI deepfake bills showed up in at least 30 statehouses

State lawmakers, Republican and Democrat, are tackling the issue themselves. Wendy Underhill, the director of elections and redistricting for the National Conference of State Legislatures, said her team has tracked 55 bills introduced in 30 states. A handful passed into law this year. California and Texas have had laws on the books since 2019.

A bill in Indiana headed to the governor’s desk after receiving bipartisan support would require ads that use deepfake technology to disclose, “Elements of this media have been digitally altered or artificially generated.” The law will apply to pictures, video, and audio. Affected state and federal candidates can sue for damages in civil court.

“It’s a pretty easy bill to get passed because nobody here wants people to be bamboozled about what they’re seeing,” said State Rep. Julie Olthoff, the Republican who sponsored the bill. “And secondly, who’s going to say ‘No’? You’re going to vote ‘No, I want people to use AI generation and do whatever they want’?”

Olthoff said she wrote the bill based on a law that was already on the books in Washington state. She said she’s not completely happy that the only recourse is financial, and said lawmakers took out language that would’ve created criminal penalties or banned the technology completely.

“If a deepfake ad runs three days before the race you lose, then it’s kind of too late,” Olthoff said. “You lost the race because of it, and all you get is whatever the judge tells you.” She added, “We might be able in future years to go a little bit further, but there’s urgency in this.”

In Kansas, state Rep. Pat Proctor, a Republican, joined with a Democratic leader to try to pass a bill that would require disclosure on deepfake ads and make it a crime to impersonate an election official, such as a secretary of state, in order to convince them not to vote. The language was inspired by the Biden robocall.

"This technology can make such realistic material that it’s indistinguishable from the real thing, and it can be done so cheaply by anybody that I think that we really need to put down some guard rails to protect voters from this stuff," Proctor said.

Proctor said the bill is currently dead, but can be brought back to life, and that could still happen. "This is definitely something that has bipartisan support because we’re both going to be victims of this and we all know it," he said.

Fake Trump video? How to spot deepfakes on Facebook and YouTube ahead of the presidential election

More: Tech giants pledge crackdown on 2024 election AI deepfakes. Will they keep their promise?

Big tech companies require disclosure of deepfaked AI

Google announced that, starting in November, it would require “clear and conspicuous” disclosures from election advertisers who use AI in photos, videos, and audio. The company’s subsidiary, YouTube, also announced in November that it would install updates that “inform viewers when the content they’re seeing is synthetic.”

Meta, which owns Facebook, Instagram and Threads, says its staff removes ads that are false, altered, partly false, or missing context; and prohibits ads that discourage voting or call into question the legitimacy of the election, or have premature claims of victory. The policy includes AI-generated ads.

Andrew Critch, an AI researcher for the University of California, Berkeley, said it needs to be illegal to produce deepfakes. He said federal agencies can establish norms, and Congress can find a bipartisan consensus on criminalizing deepfake production.

"We need deepfakes to be illegal to produce, and we also need people to be educated that they need ways of detecting what is or isn’t a deepfake," Critch said.

On Wednesday, Sens. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., and Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, introduced a bill to require disclaimers in AI-generated political advertising that would also require the FEC to address violations of the law.

Olthoff said the federal government should take action so that federal campaigns aren't forced to sift through a patchwork of state laws. "Now you have to figure out what the disclaimer is and it’s different in different states," she said. "Or if you’re harmed, you have to do a lawsuit in 30-plus states."

Weissman said passing a rule by the FEC might not fix all the challenges of deepfakes, particularly because the FEC often deadlocks when it votes on enforcement decisions, meaning they take no action. But he said there at least needs to be a rule on the books.

“We need enforcement to stop burglary and robbery, but if it’s just legal altogether, we should expect a lot more people to steal things,” he said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: AI deepfakes are part of 2024 election. Is federal regulation coming?