Anthony Fauci on contradicting Trump, combating COVID and becoming a hero ? and a villain

WASHINGTON ? Anthony Fauci has not lived the life he expected.

A boy from Brooklyn, the son of a pharmacist whose family lived above the store, he was drawn to medical school after his hoop dreams ended at Regis High School, courtesy of his 5'7" height. He became an immunologist and then director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, doing research and treating patients in cases involving the world's deadliest plagues, from AIDS to Zika.

Then came COVID-19.

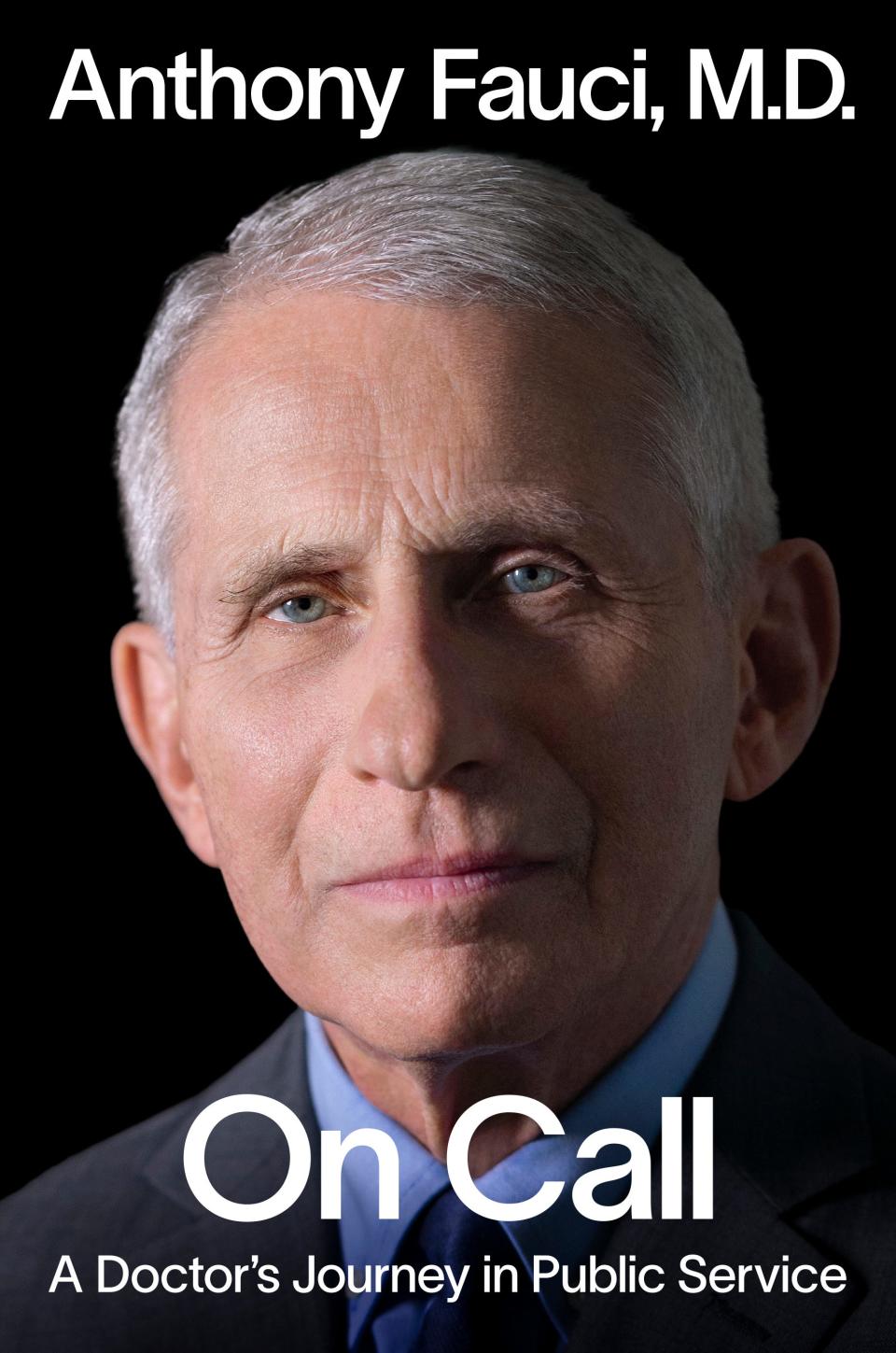

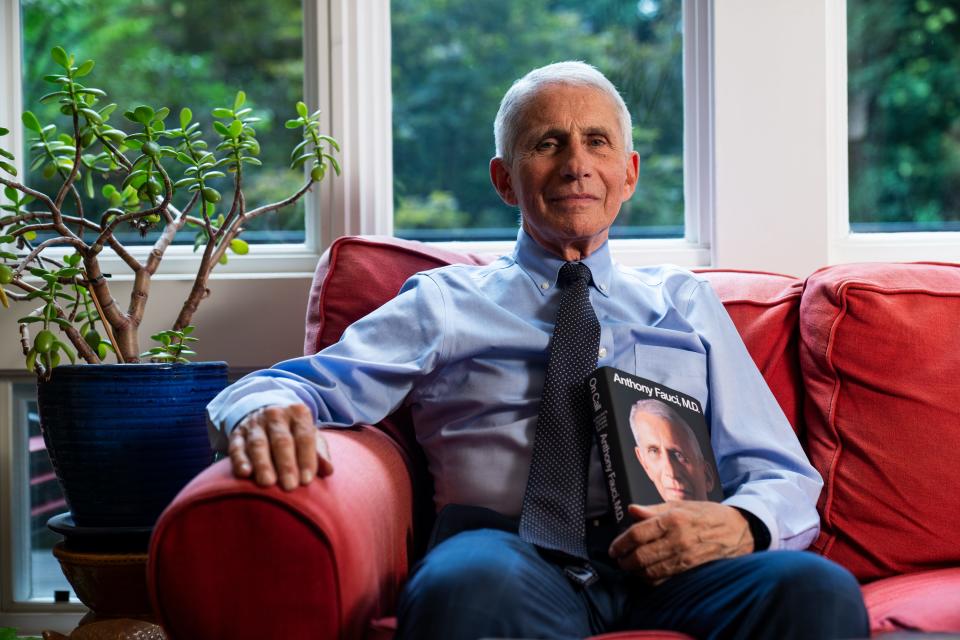

"It's sort of surrealistic," Fauci told USA TODAY in an interview about his memoir, "On Call: A Doctor's Journey in Public Service," published Tuesday by Viking. "Go back years when I was in medical school, did I ever think that I would be in a situation where millions and millions of people love me for what I've done, saving millions of lives ... and yet have some people who actually want to kill me?"

![Jun 13, 2024; Washington, DC, USA; Anthony Fauci, the former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, speaks about his new memoir "On Call," which is schedule to be released on June 17, 2024.. Mandatory Credit: Josh Morgan-USA TODAY ORG XMIT: USAT-882083 [Via MerlinFTP Drop]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/0Uy_6dxbrvUSPdWp38bnHQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY0MA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/usa_today_news_641/cc92006e93ec8f1e7b3fc1bc56d95adb)

During the worst global pandemic in a century, Fauci became the nation's communicator in chief, a hero to many Americans as a straight talker even when his candor put him at odds with the nation's commander in chief. But some on the far-right accuse him without evidence of incompetence and corruption and even of being at the center of fantastical conspiracy theories about how COVID started in the first place.

The acknowledgements at the close of the 464-page book reflect Fauci's newly bifurcated world. He thanks superstar singer and activist Bono "for his encouragement and friendship" but also expresses "special gratitude" to the security details that by necessity became part of his daily routine.

"Do I feel safe?" Fauci mused, repeating a reporter's question. Yes, he answers. But.

"But I still think deep down that there's a possibility that somebody's going to kill me."

Seven presidents, one 'complicated' relationship

During 38 years as director of the Infectious Diseases Institute ? one of the longest tenures anyone has ever had as the senior official of a federal agency ? Fauci dealt directly with seven presidents, from Ronald Reagan to Joe Biden.

He describes the relationship he had with the sixth, Donald Trump, as "complicated."

From the outset, the blustery president seemed to like him, Fauci said. "He sort of took to me like a guy from New York, 'I'm from Queens; he's from Brooklyn.' He had that New York swagger about him, and I had a little bit of that New York swagger and we seemed to relate to each other."

Fauci also had the unexpected endorsement of Lou Dobbs, a vocal Trump backer who then hosted a show on Fox Business and had interviewed Fauci through the years.

But as the COVID pandemic raged, Trump became increasingly irate at the scientists who rebuffed his entreaties to declare the virus under control ? well before it was ? and rejected the tantalizing remedies he was hearing about from unorthodox sources.

Fauci pushed back in private and in public until White House officials, unable to shut him up, barred him from going on Sunday morning TV shows.

"I had to, in order to preserve my own personal integrity and my responsibility to the American public, had to publicly disagree with him," Fauci said. Among other things, there was the notion that COVID would soon "disappear," or that hydroxychloroquine could treat it. "It might hurt you," Fauci cautioned Americans about the president's prescription.

His most jarring exchange with Trump came on June 3, 2020, after Fauci had told a medical journal that, even after developing a COVID vaccine, Americans might need to get booster shots down the road.

Sitting in his family room late that night, Fauci got a call from a number that was blocked. The White House was on the line, and Trump was in a rage.

"He said he loved me, but the country was in trouble, and I was making it worse," Fauci would recall. "He added that the stock market went up only 600 points in response to the positive Phase 1 vaccine news and it should have gone up a thousand points and so I cost the country one trillion f---ing dollars."

The "unnerving" call gave him whiplash, Fauci said. "He starts off by saying, 'I love you,' and then he blasts you," he said. "And then he ends by saying, 'Well, are we OK? We're good, right?"

The last time the two men spoke was the Sunday morning before the 2020 election.

This time, Trump's angry phone call was prompted by a newspaper interview in which Fauci warned that the country was in "for a whole lot of hurt" from COVID in coming months. New daily cases were hitting record highs. But on the campaign stump, Trump had been promising that the country was "turning the corner" on the virus.

"Tony, I really like you, and you know that, but what the f--- are you doing?" Trump demanded in a tirade punctuated by profanity. "Everybody wants me to fire you."

(Actually, since Fauci was a civil servant, not a presidential appointee, Trump didn't have the power to fire him.)

"I am going to win this f---ing election by a landslide. Just wait and see," Trump predicted, then concluded with his customary bonhomie: "OK, Tony, I will see you in a couple days. Take care."

They never talked again.

His view of Trump now?

Fauci is sitting in that family room of the house he bought in a leafy Northwest Washington neighborhood in 1977, when he was just starting out, before he married bioethicist Christine Grady and reared their three daughters here.

Family photos are displayed on every shelf and eclectic collections of music ? from country music hits of the 1960s to Christmas carols ? are stacked on the upright piano. The couch is rumpled and potted plants are clustered along the windows that open into the back patio.

At 83, he still has the athletic build of a runner, hauling nine boxes of books from the front stoop to the dining room, where he'll autograph them for his publisher. He retains a scientist's careful mien, but he no longer has the exhausted, wired air that marked his final years in government.

His view of Trump now?

"Well, my view of him during the outbreak is that anybody who just egregiously doesn't tell the truth worries me, when that person is the president of the United States," he said, "I think there would've been a lot more people taking vaccines if he actively promoted vaccine." Trump had pulled back on his vocal endorsement of the COVID vaccine after some core supporters booed the shots as suspicious or even dangerous.

"One of the several unfortunate aspects of the outbreak was that it occurred at a time of profound divisiveness in our society," Fauci said. "You have people who are getting vaccinated or not based on political ideology. They're wearing a mask or not based on political ideology."

In the end, vaccination rates in the United States lagged most other developed countries. More than 1.1 million Americans died.

From a public-health standpoint, he said, "it didn't turn out optimally, that's for sure."

Holding a record that Guinness doesn't track

Fauci, who retired in 2022 from the National Institutes of Health, is now a professor at Georgetown University with an appointment both in the school of medicine and the school of public policy, two worlds he has long bridged.

Fauci calculates he may have testified before Congress more times than any other person in history, a statistic Guinness World Records doesn't track. He wrote his memoir in part to encourage young people to go into public service, although his experiences in recent years may seem to some more like a cautionary tale.

This month, now a private citizen, he sat before the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic, where he did more listening than talking. Democratic members of Congress exalted him; Republican members of Congress reviled him.

"You belong in prison," firebrand Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene declared, saying she would refuse to use the honorific "Dr." for him. At one point, she held up a photograph of beagles, denouncing the use of dogs in federally funded research, and accused him of "repulsive evil science."

Fauci's expression more often betrayed bafflement than anger.

"Well, the first thing is, you have to keep your composure and keep your cool because when people are acting extraordinarily inappropriately who shouldn't be, given their position, you can't stoop to them and act in an inappropriate way," he said. "So you just answer the question the best you can. You can't let them push you around, but you don't get into a silly fray."

He says wild accusations from members of Congress can fuel the death threats he has faced. In 2022, a West Virginia man was sentenced to three years in federal prison after sending emails that threatened to kill Fauci or members of his family. They would be "dragged into the street, beaten to death, and set on fire," he had vowed.

Fauci acknowledges that he and the scientific community made some mistakes in dealing with COVID. The development of a safe and effective vaccine in less than a year was an historic achievement, he says, but the advice the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others gave Americans sometimes conveyed more certainty than they had.

When more was known about the disease, the official advice would change, or should have, sparking confusion and suspicion.

"When you think back on it, we should have emphasized a bit more the uncertainty," Fauci said. While the public statements included cautionary words about how much wasn't yet known about the disease, they often left the impression that the advice on the value of wearing a mask or the need to maintain a 6-foot distance from others was firm and final.

"Some of the things that the CDC said and the way they said it was confusing the public," Fauci said. On late-night conference calls behind the scenes, "I'm saying, 'This is not going to fly; you can't say it this way.'"

The biggest controversy has been over the origins of COVID, over whether it was the result of a natural jump from animals to humans or the consequence of leak from a Chinese lab. Fauci thinks it was probably a natural jump but says he has an "open mind" about a question that may never be answered.

He says that the molecular structure of COVID-19 rules out the possibility that U.S.-funded research in Wuhan, China, led to the pandemic, an allegation pressed by some.

Given China's refusal to cooperate with a serious inquiry, he said, "I think there's a reasonable chance that we might not ever know where it came from."

![Jun 13, 2024; Washington, DC, USA; Anthony Fauci, the former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, speaks about his new memoir "On Call," which is schedule to be released on June 17, 2024.. Mandatory Credit: Josh Morgan-USA TODAY ORG XMIT: USAT-882083 [Via MerlinFTP Drop]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/uD2xVjsE9AOJQ3csFbCO7g--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY0MA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/usa_today_news_641/53ccf20c1b14fedcfe1f7a3f39acc7f4)

The next pandemic: When. Not if.

In the United States, the missteps on COVID will make it harder for scientists to command the public's trust when the next dangerous virus emerges, Fauci said. "I don't think it's an irreparable damage to the faith in science, but I think it needs to go back and try and rebuild that trust" when that happens.

When. Not if.

Because another pandemic will happen, he said ? in a year. Or maybe 50.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Anthony Fauci on the fight to combat COVID and contradicting Trump