Beale Street robbery: After 20 years, attorneys say man wrongly convicted could be released

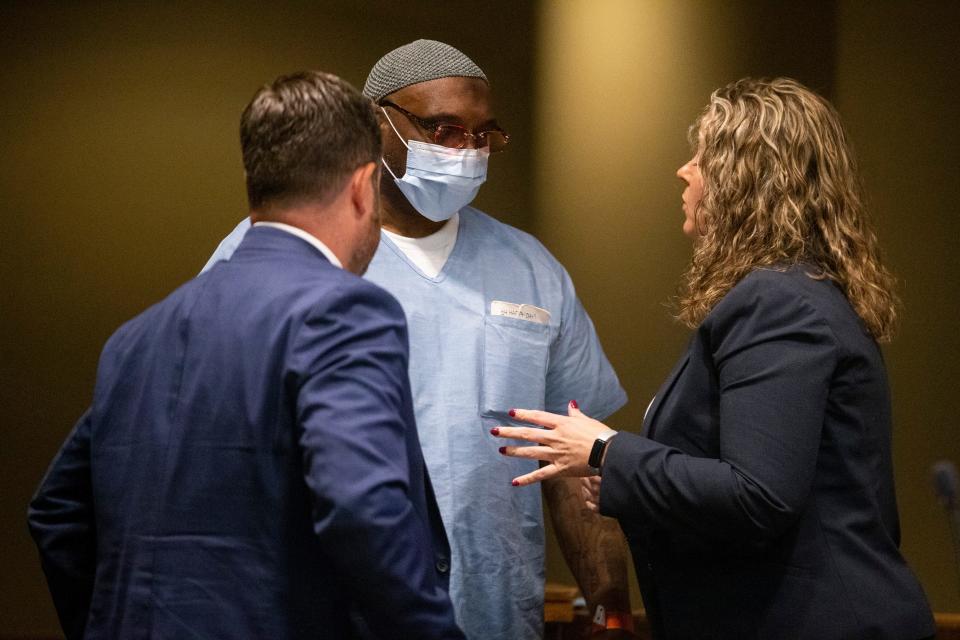

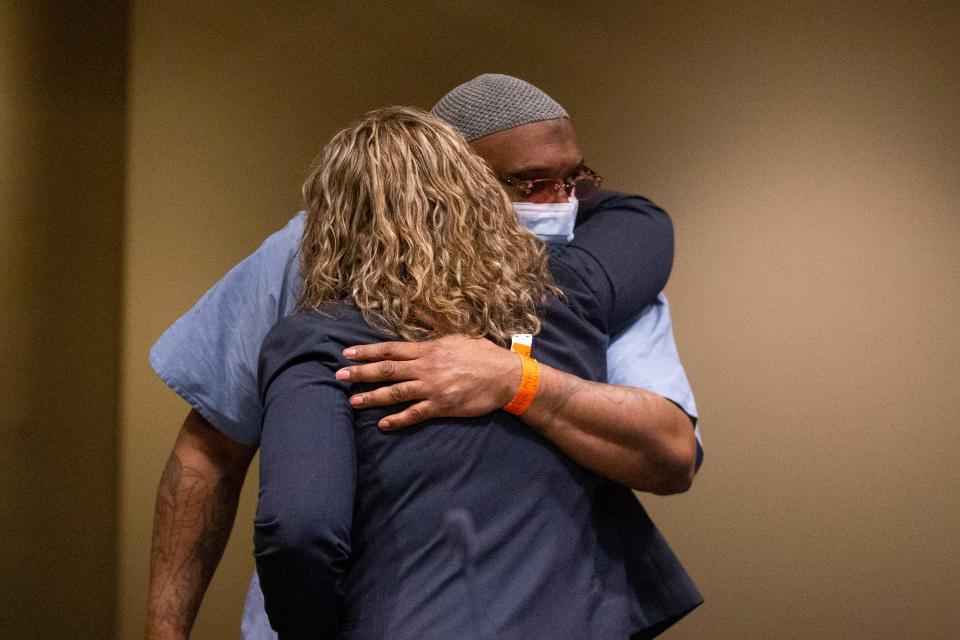

A Memphis man has been sitting in prison for almost two decades for a high profile robbery and kidnapping he did not commit, his attorneys argued in Shelby County Criminal Court Wednesday and Thursday. Now he could be exonerated.

In court, attorneys pointed to a number of problems with the case that they say led to a conviction from two eyewitnesses ― that they assert were faulty ― and a shaky informant. They also cited legal and ethical violations from the Memphis Police Department, the prosecutor and the convicted man’s original defense attorney.

Artis Whitehead, 60, was sentenced to 249 years in prison after being convicted on five counts of especially aggravated kidnapping, two counts of especially aggravated robbery, two counts of aggravated assault, one count of aggravated robbery and one count of attempted aggravated robbery in 2004.

The conviction stemmed from a May 2002 incident where a man tied up five employees of B.B. King’s Blues Club on Beale Street at gunpoint, trying to get one of them to open the restaurant’s safe that was located in the basement.

The first man to be held at gunpoint tried to wrestle the gun from the robber, but the gun fired and he was tied up. Later, after four more people went to the basement and were tied up, that same man got free and grabbed for the gun again, which was then fired and a bullet grazed the man’s head.

None of the employees could open the safe, and the robber eventually left the restaurant. He did not “steal any money or thing of value from B.B. King’s,” the filing from Whitehead’s current attorneys ― from the Tennessee Innocence Project ― said in a postconviction filing. The robber did, however, steal about $520 in cash, three rings and a watch from the people held captive in the basement.

When MPD officers arrived at the scene, witnesses said the man who robbed them was between 5’4” tall and had a “slim build,” weighing between 135 and 150 pounds. The man wore a hat and sunglasses and was in his 30s or 40s.

In communications, MPD said the suspected robber was “5’6 to 5’8, thin build, dark complexion, mustache, 35 to 40 years of age.”

The case, however, went cold for months after being on the front page of The Commercial Appeal the following day. There was no footage of the man’s face, as when he walked into B.B. King’s he carried a box that shielded it from security cameras.

Whitehead’s attorneys said in court Thursday that police did not document any leads for the next eight months.

It was not until Jan. 24, 2003, at 3:04 p.m. that police had a lead when a man called CrimeStoppers and named Artis Whitehead as the man who committed the robbery at B.B. King’s.

But Jessica Van Dyke, the executive director of the Tennessee Innocence Project, said the tipster was not a standard citizen who called CrimeStoppers, but a convicted felon who was facing additional prison time and looking to have it trimmed down. Van Dyke also said the man was a confidential informant for MPD.

That tipster was identified in court during the initial trial, and in court Wednesday and Thursday, as Greg Jones, who is currently in federal prison serving time for robberies he was convicted of.

An informant masked behind a CrimeStoppers tip

While investigating Whitehead’s case, the Tennessee Innocence Project reached out to Jones in prison to ask about the tip.

“Several weeks before [Whitehead] was arrested, a call was placed to CrimeStoppers implicating him as being responsible for that crime,” Jones wrote in a letter that the Innocence Project entered into evidence. “That call was made from [MPD] Sgt. J.R. Howell’s mobile device, right there inside of the robbery squad open office."

The Tennessee Innocence Project attorneys said in court Wednesday that this statement was verified by MPD’s own records, which they said show Howell was investigating Whitehead earlier that day.

At the time Jones made the call, according to MPD records obtained by the Tennessee Innocence Project, he was on trial for a robbery and was frequently visiting MPD to report people for crimes in an attempt to have time cut from his impending prison sentence.

CrimeStoppers tips are anonymous, and there is no way to subpoena testimony from people who call the tip line. Confidential informants, however, can be called to testify so a defendant can question the validity of their accusations.

Jones provided MPD with other names as well, prominently a robbery and homicide at Union Planters Bank, which MPD officers investigated and found to be false. Detective Bart Ragland, at Jones’ sentencing, testified he was untruthful when naming people in other crimes and that he “inculpated innocent people,” Van Dyke said Wednesday.

But Van Dyke said that same level of scrutiny was not given to the information about the B.B. King’s robbery, and Ragland, one of the MPD detectives that worked with Howell at the time, testified that Jones was instrumental in arresting Whitehead.

“There were no other leads prior to [Jones’] involvement,” Ragland said.

Jones ultimately did not get a reduced sentence for providing officers with Whitehead’s name.

CrimeStoppers tips are anonymous, and there is no way to subpoena testimony from people who call the tip line. Confidential informants, however, can be called to testify so a defendant can question the validity of their accusations.

'That is a clear deception'

Former police officer Jack Ryan, who is also an expert in law enforcement practices across the nation, testified Thursday that hiding an informant constitutes a Brady violation ― meaning the prosecution did not hand over evidence that could have been beneficial to the defendant.

He also said, in a report he wrote based on the Whitehead case files, that hiding an informant was “deceptive.”

“Hiding the informant behind the CrimeStoppers tip, that goes beyond incompetence. That is a clear deception in my mind,” Ryan said.

Ryan added that the identity of people who call CrimeStoppers is often not known by police. But police knew Jones to be the person who gave Whitehead’s name, and so did the lead prosecutor on the case at the time, former Shelby County District Attorney Amy Weirich, according to Van Dyke.

Van Dyke argued that Weirich, knowing about Jones being the informant, was bound by law to give that to the defense as evidence.

“There are also Brady violations from the district attorney’s office,” Van Dyke said in closing Thursday. “I want to encourage the court to really carefully look at the language that was used by Ms. Weirich when she made this disclosure, that [Jones] was ‘in the robbery office on another unrelated matter.’ She mentioned Union Panter, so she has some knowledge of what Mr. Jones has been up to, but she never goes any further than to say he’s a CrimeStopper here.

“You would hope that an ADA who’s about to convict someone and put them away for 249 years would ask more questions. I don’t know what happened. I only know what was put on the record, and it was not a full, accurate disclosure of what Greg Jones did.”

Conflict of interest opens door to potential exoneration

Not only did prosecutors and police know Jones’ identity, Van Dyke said Whitehead’s initial defense attorney, Howard Wagerman, had information about the informant too ― and that the knowledge presented a conflict of interest.

Wagerman, at the time, worked in the same law office as the attorney who was representing Jones in federal court. That attorney, Scott Hall, was attempting to have Jones’ sentence lowered for providing the tip in the B.B. King’s robbery, and sat in during much of the Whitehead trial, according to court transcripts the Tennessee Innocence Project entered into evidence.

But that only came out in court because the federal prosecutor working Jones’ case had visited 201 Poplar “to get an order entered on something unrelated,” according to Weirich at the time, and asked about the Whitehead case.

“[The federal prosecutor], in fact, made the comment ― she said, ‘If I knew this trial was going on, I would have called you all or come over here,’” Weirich told the court in 2003, according to court transcripts. “I think maybe when she saw Scott Hall sitting here, she’s the one that thought, ‘Well, that’s funny to me because he represents Gregory Jones in federal court, and here’s Mr. Wagerman and his partner’s representing someone that he…”

But the end of that sentence was cut off in the Tennessee Innocence Project’s court filing.

The conversation, according to Van Dyke, happened when the jury was not in the courtroom. Neither was Whitehead, he said in court Thursday.

“What’s interesting when you step back and look at what’s been presented is that without the conflict of interest between Howard Wagerman and Scott Hall, we wouldn’t know what we know today,” Van Dyke said.

That was the only time Jones’ name was mentioned during the case, and ethics experts testified Wednesday that the two working in the same law office made it ethically impossible for Wagerman to thoroughly investigate Whitehead’s case.

'Imperative in this particular case'

Former Nashville Criminal Court Judge Mark Fishburn said Wednesday that Wagerman did not appear to adequately investigate Whitehead’s case.

“In fact, in [Wagerman’s] letter after the trial, he said he still didn’t know who this guy was,” Fishburn said. “And he made no inquiry with Detective Howell or, to my knowledge, made no independent investigation pretrial to find out how Mr. Whitehead’s name ever came up.”

Fishburn said that, as a defense attorney, it would be crucial to find out Jones’ role because the defense is ethically required to do its due diligence. He did, however, call the situation a “catch-22,” saying that investigating Jones would have created problems for Hall and not investigating him created problems for Wagerman.

“[Attacking Jones’ credibility] was imperative in this particular case,” Fishburn said Wednesday. “It would be critical for the jury to understand the behaviors in this case, detectives and how they tried to cover up Mr. Jones’ identity by making him a CrimeStopper tip rather than what he really was. I don’t even think he was a confidential informant. I’d say it was a guy in federal court who absolutely was just trying to get the best daily good to save his own time.”

The solution, both Fishburn and ethics expert Lucian Pera agreed in court Wednesday, would have been to inform Whitehead of the conflict and have a new attorney assigned to his case. Neither of those things happened in the initial trial.

But that conflict was not the only one that occurred during Whitehead’s case. In the appeals process, his new defense team contracted an attorney to write the appeal. That attorney, at the same time he was writing the brief for Whitehead’s team, was representing Jones in his appeal.

That conflict, Pera said, was different from the one that occurred in the trial. But it existed even though the attorney, Michael Robbins, was not representing Whitehead during his appeal.

“His conflict is that he represents Mr. Jones and he is deep into the representation,” Pera told the court Wednesday. “He is, I think, also involved in trying to get some kind of credit for Mr. Jones’ CrimeStoppers tip. Yet, at the same time, he’s drafting appellate briefs on a direct appeal for Mr. Whitehead.”

Robbins reached out to the Tennessee Board of Professional Responsibility, which is the ethical governing body for lawyers, to consider if representing Jones and writing the brief for Whitehead was a conflict of interest. Pera said that does not absolve the conflict.

“The advice [the board] gives, just like the advice any of us give as lawyers, is only as good as the information [the board] gets,” Pera said, later adding that he does not see “any scenario in which a fully informed person at the board, hearing the facts about Mr. Robbins, wouldn’t have flagged this as a serious problem. I just don’t think that’s possible.”

Whitehead’s appellate brief did not raise questions about Jones or the conflict of interest in the initial trial.

The appeal also did not try to point to prosecutorial misconduct or any flaws in the MPD investigation.

The eyewitness testimony problem

Attorneys with the Tennessee Innocence Project spent much of Thursday’s hearing talking about the difficulty in having concrete eyewitness testimony, along with pointing out discrepancies between the description witnesses gave the day of the robbery and Whitehead’s stature.

During the initial investigation, witnesses told police the robber was between 5’4” and 5’10” ― and MPD detectives narrowed that height range to between 5’6” and 5’8”. Witnesses also described the robber as being “slim” and weighing between 135 and 150 pounds.

Whitehead is 6’0” and, at the time of his arrest, weighed between 245 and 250 pounds. That weight, he said in testimony Thursday, was from muscle mass since he would “be in the gym four or five days out of the week.” Whitehead said he now weighs about 230 pounds.

More: 'Get out of our silos.' Memphis, Shelby Co., state officials meet for crime summit

Only two of the six witnesses of the robbery positively identified Whitehead during his initial trial, though both said there was a “change” in the robber’s appearance from the day of the robbery to the day of the trial, referencing Whitehead’s large stature.

One witness said Whitehead was larger than the robber and that the robber had hair around the back of his ears. Whitehead had a shaved head at the time.

Another witness, whose initial witness statement was missing at the time of trial and not entered into evidence, also said Whitehead was “beefier” than the robber.

Both witnesses identified Whitehead as the person who robbed B.B. King’s in trial and in a lineup. The other four witnesses did not identify Whitehead in either circumstance, with one at trial saying the robber was “average” sized and that Whitehead “doesn’t seem to be an average guy.”

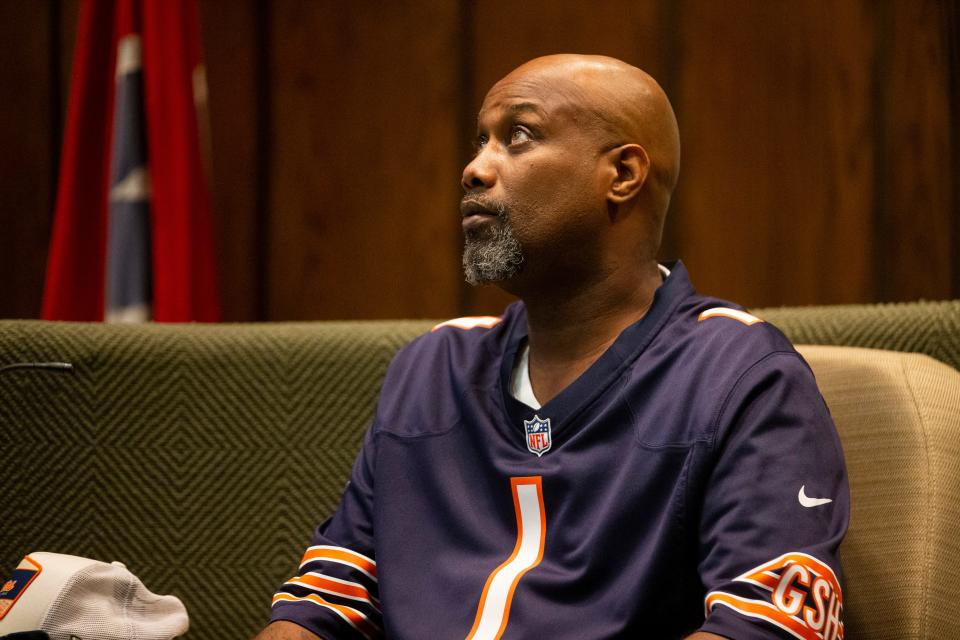

One witness who was 6’0” tall, said he did not see the robber’s face, but said he was taller than the robber. Another witness, Mark Hearn, was asked during the original if Whitehead looked like he could have been the robber at the B.B. King’s that day.

“It don’t look like it to me,” the Hearn responded.

Hearn also testified Wednesday.

Witnesses for the defense in that initial trial testified that Whitehead had always been that size, saying that he did not bulk up in the months since the robbery occurred. One noted that he was actually smaller since his arrest because he was working out less frequently.

“The most interesting thing in the entire argument was the state’s position at this trial,” Van Dyke said Wednesday. “I’ve never heard the state argue this at a criminal trial before, but their position was: ‘Height and weight doesn’t matter.’ In a case that was solely about eyewitness identification, I don’t know how this won the day for them.”

Witnesses were called in to identify Whitehead in a lineup nearly eight months after the robbery took place. Experts in eyewitness testimony said at the Thursday hearing that memory drops “precipitously” hours after an event like this takes place, especially when the victims are under intense amounts of stress.

“There’s some research showing that a lot of jurors believe that stress burns something into your memory, which is, in fact, the opposite is the case,” said Margaret Bull Kovera, a professor and researcher at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “We know that the presence of a weapon, whether seen or implied, can cause witnesses to focus on the weapon as opposed to the face. So, it draws attention away from the face and you need attention to be able to form a memory about a face.”

Those factors ― combined with the fact that the victims did not see the robber’s face for much time, the length of time between the event and lineup, and that the robber was wearing a hat and sunglasses ― made Kovera’s confidence in the accuracy of the eyewitnesses picking Whitehead out of the lineup accurately sit at a low level.

What happens next?

Shelby County Criminal Court Judge Jennifer Fitzgerald will provide a written ruling, which she said she hopes to have “done rather quickly.”

The Shelby County District Attorney’s Office requested she issue a written ruling, with time for the DA’s office to respond to the evidence presented at trial.

Should Fitzgerald rule in favor of Whitehead and the Tennessee Innocence Project, the case would ― essentially ― go back to square one, and the decision as to whether or not to re-try the case would fall to the DA’s office.

If Shelby County District Attorney Steve Mulroy declines to re-try the case, Whitehead would be a free man for the first time in over 20 years. The case would be cleared from his record, and it would be as if he was arrested but never charged.

In essence, that decision by the DA’s office would declare Whitehead legally innocent of the robbery at B.B. King’s ― something he has said for over two decades.

Lucas Finton is a criminal justice reporter with The Commercial Appeal. He can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @LucasFinton.

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: Memphis man may be exonerated decades after B.B. King's robbery conviction