Billions in federal child care relief just expired. Costs are already skyrocketing.

BriAnne Moline has been “seriously considering” shutting down the early-childhood education program she runs out of her home near Missoula, Montana.

The 38-year-old single mom of four has sacrificed a lot to get where she is today – from moonlighting at McDonald's and Michael's to owning a business in a profession she loves. Housing policies forced Moline to move her business and family twice over six months in 2019, while she was pregnant with her fourth child, before she finally found her current rental. Then came COVID-19, which brought more instability. The resulting stress caused Moline to lose significant weight and develop chronic migraines.

Despite overcoming all that, in the past few months she has started to question whether it was worth it. Moline lost her one remaining employee, and nobody has responded to job postings. She doesn’t have the capacity to serve more than five kids, which leaves her with enough money to cover rent and little else. To put meals on the table and gas in the truck, she has four additional part-time jobs, gives plasma twice a week and makes frequent trips to the food pantry.

“The only thing that keeps me here is the fact that I’m just really passionate about what I do,” Moline said as she soothed a toddler. “Life throws curveballs at you, and you just have to learn how to juggle.”

Across the country, the child care industry is crumbling in real time. Federal relief money that helped keep the sector – and parents – from going under during the pandemic is evaporating if it isn’t already gone. That includes the 2021 American Rescue Plan’s historic $24 billion infusion into the sector, which allowed tens of thousands of centers to avoid permanent closures and officially expired Sept. 30.

On Wednesday, President Joe Biden asked Congress to extend the funding for another year as part of a broad ask for spending on domestic priorities. For child care, Biden proposed an additional $16 billion "to help keep child care providers afloat, mitigating the likelihood that providers will close or raise costs for families."

The discontinuation of those dollars amounts to one of the latest, and most debilitating, curveballs Moline has faced yet. She doesn’t know if her business is going to make it. The money, which ran out months ago, allowed her to provide benefits to her then-three full-time employees; now, if she manages to hire someone, she could barely offer more than minimum wage.

“We’re just going to see more programs closing, more burnt-out educators and more staff turnover.”

‘Child care cliff’: A broken market’s slow collapse

Montana is one of six states where, according to research by the left-leaning Century Foundation, or TCF, the number of licensed child care programs could be cut by half or more now that pandemic-era relief dollars have stopped flowing. In another 14 states, a third of programs could be forced to close.

Overall, researchers for the foundation predicted 70,000 programs could shutter, with 3.2 million children losing spots. Large, corporate child care networks may not see significant effects, but echoing trends that predated the pandemic, the most vulnerable programs are those run out of homes, as well as those who serve infants and toddlers.

Some states, from Alaska to Vermont, have set aside funding to stave off the cliff. In Minneapolis, the state Legislature approved more than $1 billion, including hundreds of millions doled out over the next four years, to continue the improved pay and benefits that were available with the federal relief dollars.

In Wisconsin, after Republicans repeatedly rejected Gov. Tony Evers’ proposals to continue a federally funded pandemic-era child care program with state dollars, the Democratic governor announced a smaller package of “emergency funding” last week. The money will cover the program through summer 2025.

At least 18 states, according to a Child Care Aware analysis, have increased spending on child care this year. But these budget increases were often after yearslong fights – and even then, the allocations have been scant in comparison to the federal relief, which in some cases began drying up months ago.

“The funding that’s required is too significant for states to try to do this alone,” said Rachel Wilensky of the Center For Law and Social Policy, a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization advancing policy solutions for low-income people.

Providers across the country told USA TODAY they’re quickly finding it more difficult to stay open, which threatens to turn more communities into child care "deserts." They either can’t find staff, can’t fill seats or can’t keep up with bills. Often it’s a combination of all three.

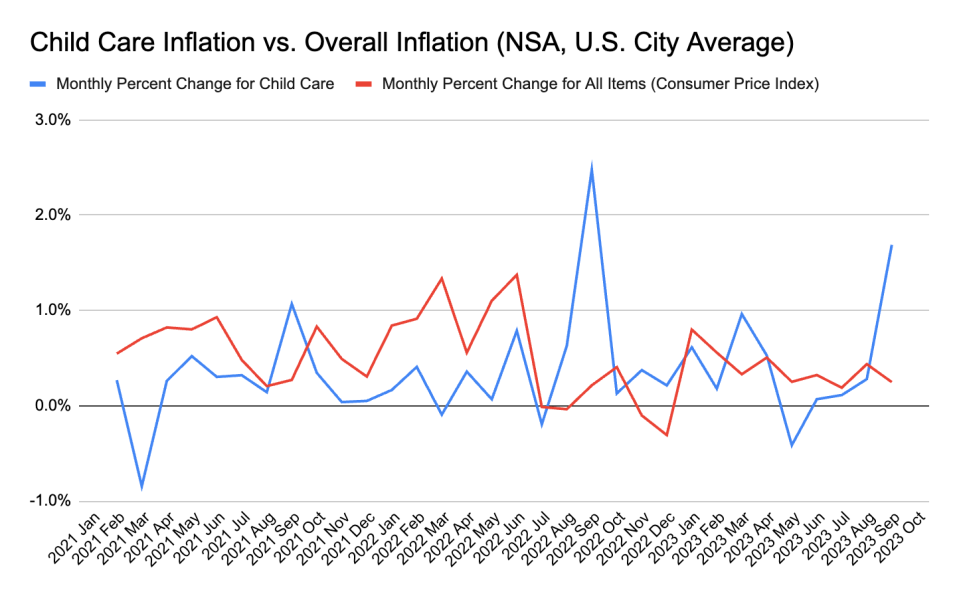

Parents, meanwhile, are starting to see the effects on their wallets and their kids’ classrooms. Teachers are leaving. Grants to help providers pay higher wages are being cut. Child care prices, which from July 2022 to July 2023 rose at twice the rate of inflation, have continued to skyrocket. Over September alone, child care prices increased by 1.7%, at least twice the overall month-to-month inflation in the past year, Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows. Prices are the highest they’ve been all year.

All of this, says TCF’s Julie Kashen, is a sign of what’s to come. “The end of the funding was abrupt; the impact on children, families and the child care sector will be slow,” Kashen said.

“What we know about child care providers is that they are doing this work because they want to serve children, they want to serve families, they know how important their jobs are to both of them. And they're going to do everything they can to stay open as long as they possibly can.”

But that means raising tuition and cutting salaries and downsizing operations, all of which – without the public funding – can make closing inevitable.

What happened on September 30? Worries of a child care cliff as emergency federal funding runs dry

Why is child care so expensive but its workers so underpaid?

Child care is essential to the nation’s economy: Roughly 2 in 3 kids under age 6 have their parents in the labor force.

Yet that care costs more than $1,000 a month for a baby on average, which over a year is often more than public college tuition. More than half of families spend at least a fifth of their incomes on child care, according to a survey last year from Care.com.

Despite the price tag for parents, many center owners are in debt. The national median worker made just $13 an hour last year. According to a recent analysis by the National Women’s Law Center, pay for early educators continues to lag behind other low-paid professions. This despite many, including self-starting women like Moline, pursuing four-year or even advanced degrees.

“We do thousands of jobs – we are business owners, we are psychologists, we are therapists. We do jobs that are meant for all kinds of people but as one person,” Maria Amado, a home-based care provider in Connecticut, told USA TODAY in Spanish. “We are just trying to survive, always trying to figure out a way to stay afloat.”

Why doesn’t the math add up? Early-childhood education, like its K-12 counterpart, is an expensive enterprise – it requires highly trained, passionate, nurturing educators; safe and stimulating classrooms; and resources for play and learning. Yet unlike K-12 schools, early-learning programs receive almost no public funding, meaning tuition has to cover the bulk of expenses, from wages to rent.

The federal Early Head Start and Head Start programs serve fewer than half of children in poverty, including just 9% of poor infants and toddlers. The federal child care subsidy program serves fewer than 1 in 6 eligible kids.

“Early childhood educators and teachers are the one profession that touches all other professions. If we don’t work, nobody else works,” said Adrienne Briggs, a home-based child care provider in Philadelphia with a master’s degree who – after taxes and with the help of a second job – makes just $50,000 to $60,000 a year. “But we are the least respected.”

Various researchers and providers told USA TODAY the federal money brought changes that made it feel, for the first time ever, as if policymakers were finally acknowledging the importance of the child care industry.

“There was this glimmer at the beginning of the pandemic, where people called child care and early learning educators and programs ‘essential,’” said Michelle Kang, CEO of the nonprofit National Association for the Education of Young Children, or NAEYC. “For a moment, the field felt very seen because parents realized, ‘Wow, I can't engage in the work that I'm doing without having the caregivers and the early educators who are supporting the care of my own children.’”

But that wake-up call didn't bring a permanent reckoning, nor did the money ever bring full stability. And now that it has fizzled out, many providers are back in triage mode.

“The bottom line is that the (American Rescue Plan) stabilization grants helped keep providers open,” Kang said. “And with the money running out, they're faced with some awful decisions.”

Federal aid helped daycares stay open. Then the help wore off

Parents struggle to find affordable child care, desperate for relief

Some members of Congress want to boost child care dollars or at least extend the relief funding. But such proposals, despite relative bipartisanship on early-childhood education, have often faced fierce resistance from Republicans who oppose more federal spending.

Without public support, many centers and other providers can’t raise wages to the level needed to attract staff. That limits the number of children they can serve. Many will then be forced to rely even more on families for revenue. In one NAEYC survey, 43% of centers and 37% of family care providers said they’d have to raise rates without the funding – a trend that’s already being reflected in the federal data.

That’s on top of rising prices generally – food, gas, utilities, taxes. And it’s on top of the discontinuation of other pandemic-era relief programs such as the expanded child tax credit that helped cast a wide safety net for families. In recent months, families with children have experienced material hardship at levels last seen in 2020, according to surveys regularly conducted by researchers based at Stanford.

Meghan Higle, a mother of two and former early childhood educator also in the Missoula area, said she’s all too familiar with that trend.

Until a year ago, Higle, who has a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education and a master’s in curriculum and instruction, was working her dream job. She was a teacher at the university’s early-childhood education lab school.

But she was forced to quit after giving birth to her second child. Higle gets a decent deal for her preschooler’s care, at a little more than $600 a month, as well as assistance from her mother. But infant options are just too expensive, and while the state has modestly expanded its subsidy program, her family still doesn’t qualify. “We make too much for Best Beginnings, but we quite literally cannot afford child care,” Higle said, referring to Montana's child care scholarship program.

Now she has a remote job with a child-care-related nonprofit, which allows her to care for her baby instead of paying for it and remain connected to the industry she loves. But it’s not the same as teaching – and even with the savings of not using infant care, the preschool expenses alone are becoming unmanageable. She may have to pull their 4-year-old daughter out, too.

“I feel like, with my degree and my education, I can do so much good for this industry,” she said. “I love working with providers to make their lives easier and to give them material and provide training. But I also love working with kids. And I can’t do either because I can’t pay for my own kids.”

Contact Alia Wong at (202) 507-2256 or [email protected]. Follow her on X at @aliaemily.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Federal child care relief just expired. Costs are already skyrocketing