Bipartisan health care fix dies in Senate

WASHINGTON — That talk of a bipartisan health care bill was a pleasant dream while it lasted.

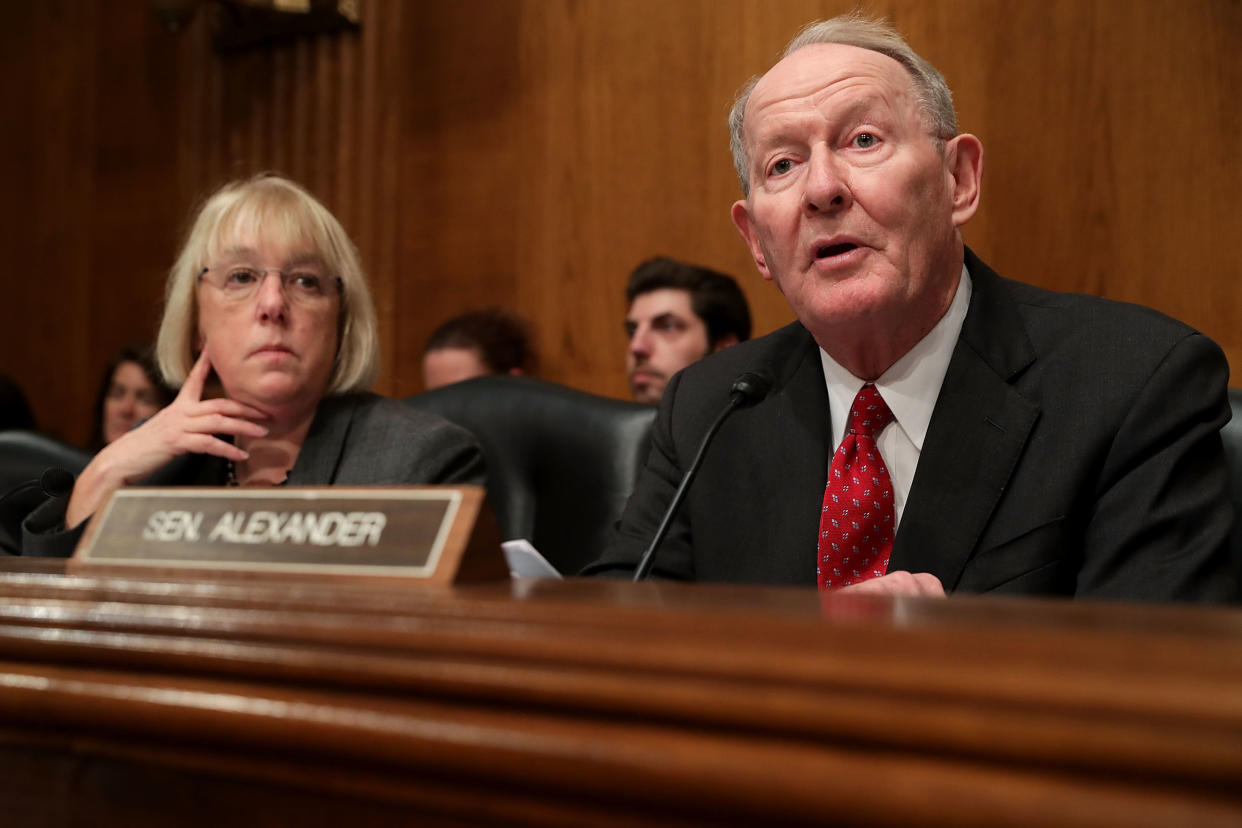

The day after Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., and Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., shelved their effort to reach an agreement on how to improve upon the Affordable Care Act, observers of the process gave varied explanations for why Republicans and Democrats failed once again to solve the problem.

The dysfunction in Washington, most seemed to agree, is driven by large forces and long memories.

The nascent bipartisan deal was deemed not aggressive enough by either side. Republicans have been talking about repealing former President Obama’s 2010 health care law for nearly a decade, and Alexander’s focus was on preventing harm to Americans who might be hurt by rising premiums in the next year. But that focus involved extending parts of Obamacare, or the Affordable Care Act, and many conservatives objected.

Democrats, meanwhile, weren’t in a compromising mood after watching Republicans fail to repeal and replace the ACA on their first attempt six weeks ago. They felt like the GOP had lost its its leverage, said Avik Roy, a conservative health care expert. And Democrats’ general antipathy toward President Trump means their default position is already to oppose anything he is trying to get done.

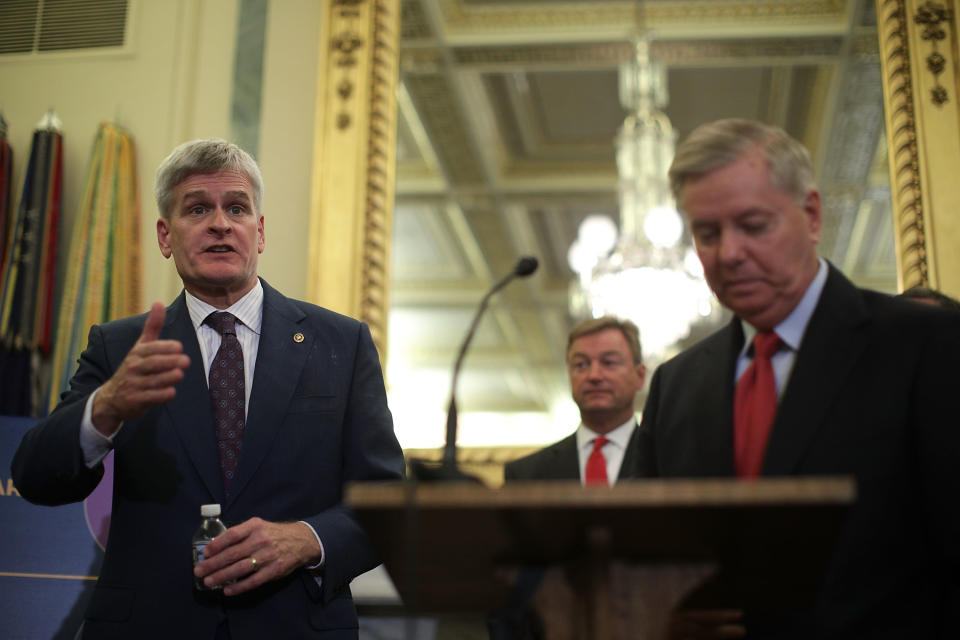

As a result, Republicans gravitated toward the so-called Graham-Cassidy legislation — named after Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La. — which focuses on giving states much greater ability to experiment with solutions to rising costs.

For their part, Democrats over the past week have flocked to the idea of a single-payer system, in essence a government-run system reviled by the president and his party.

Though Congress has been bogged down by partisan bickering for years now, this was a fairly straightforward choice for the members of what is supposed to be America’s great deliberative body. The Alexander-Murray effort represented a small-bore, incremental compromise. In response, both Democrats and Republicans chose instead to pursue a zero-sum approach that guarantees nothing but continued division.

Each side feels burned by the other’s behavior over the past decade.

Roy said the Democrats’ recent stampede to the left on single-payer coverage is caused in part by frustration born of the fact that they view the ACA as a compromise, a bill that drew on research from years ago by the conservative Heritage Foundation, and mimicked the approach taken by Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney in 2006.

“During last eight years, the thinking on the left has been we tried the incremental approach because we thought that would be a bipartisan way to move this forward,” Roy said. “We tried to be nice to Republicans by borrowing some ideas from the center right and we got accused of being socialists, so why don’t we just be socialists?”

Republicans, meanwhile, take the opposite view of the process that led to the passage of Obama’s health care law.

“I think once Obamacare was enacted on a partisan basis it was going to be very difficult to change it in a bipartisan way. The parties are entrenched and their voters are entrenched on health care,” said Yuval Levin, editor of the conservative policy journal National Affairs.

“You might be able to make modest adjustments with Democrats and a few moderate Republicans, but what’s needed is more significant, and the parties don’t agree on the direction in which to move,” Levin said.

Jared Bernstein, a liberal economist who served as a top adviser to former Vice President Joe Biden, granted that when Democrats used the budget reconciliation process to pass the ACA, allowing them to bypass the requirement of a 60-vote super majority, it set a precedent.

“Republicans have a point when they say, ‘They didn’t include us.’ That’s true,” Bernstein said. “But remember these were folks who agreed in January 2009 to block everything Obama put forth.”

And so on it goes. Washington may not be good at much these days, but it retains a highly evolved cottage industry in finger-pointing.

Add to that a president who does not yet know how to provide leadership for his own party’s congressional majority, and you have a recipe for gridlock in perpetuity.

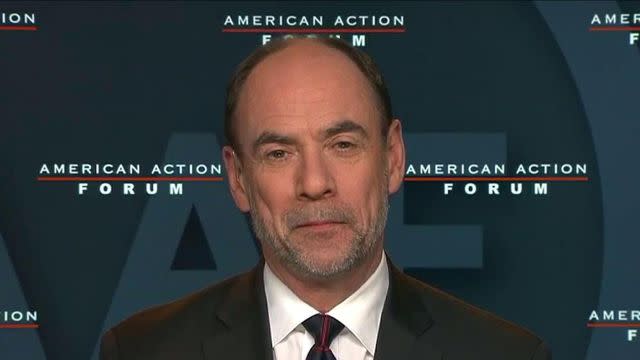

“All bipartisanship begins with the White House. Only the White House can say to the minority, ‘We understand what’s important to you, and go to their own side and say, ‘We can take care of you and we know this is a tough vote,’” said Doug Holtz-Eakin, a former Republican director of Congressional Budget Office.

Trump, by way of contrast, “sided with Republicans in Republican-only strategy” during their first attempt to repeal and replace Obamacare, “but then provided no air cover, but did undercut his own party and attack them.”

“That left us in a mess,” Holtz-Eakin said.

Another big element is the disappearance of moderate lawmakers in both parties, which is due to things like the gerrymandering of congressional districts, the rise of outside money and the fact that political parties and party leaders have less power to control members of their caucus.

“The gap to be bridged is wider and that makes it harder,” Holtz-Eakin said.

Bernstein agreed, saying that the two parties are on different planets when it comes to how they conceive of health care solutions. “It’s sort of like asking two boxers trying to beat each other, ‘Why are you fighting?’” he said.

Read more from Yahoo News: