Black history is under attack across US from AP African American Studies to ‘Ruby Bridges’

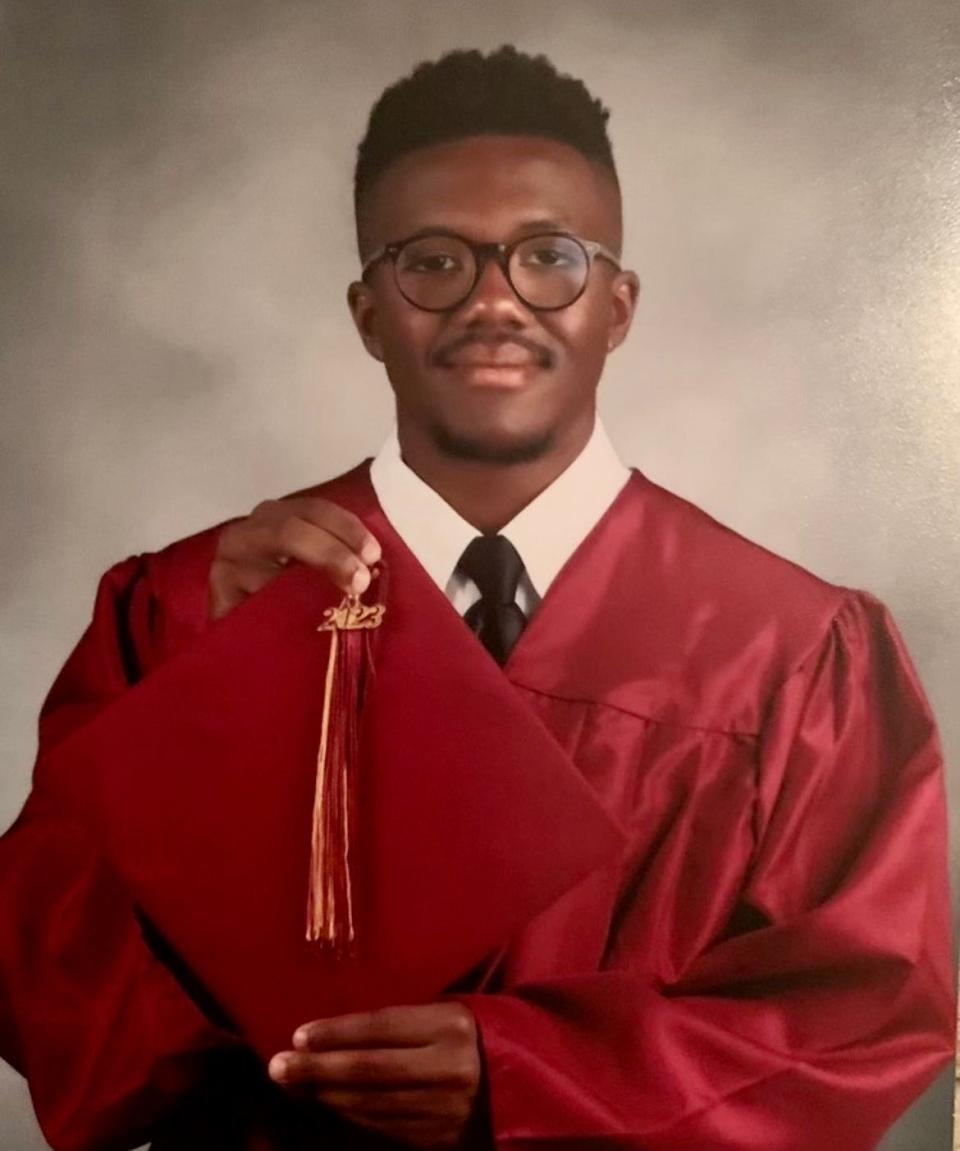

It wasn’t until his senior year of high school that Dylan Holley began to learn about all the facets of Black history. Not just snippets focusing on pain and suffering and victimization but full stories also featuring the contributions, triumphs and joys of, as he put it, “people who look like me.”

“In U.S. history (class), we’re taught to view ourselves a certain way,” said Holley, 17, a recent graduate of Maynard Holbrook Jackson High School in Atlanta.

Last fall, then a rising senior, Holley signed up to take the Advanced Placement African American Studies course, which was being tested out at Maynard Jackson High as part of a national pilot.

“I learned a different narrative when it comes to the history of my people,” he said. This narrative highlighted the African kingdoms that thrived before slavery and colonization, for example, as well as the activists who’ve challenged systemic racism through the modern Black Lives Matter movement. It highlighted the nuances of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech – and the stubborn persistence of the racism that speech 60 years ago described.

Explore the series: MLK’s ‘I have a dream’ speech looms large 60 years later

Opportunities such as these to learn a more inclusive version of the country’s history are, after decades of advocacy and activism, becoming more common in the nation’s public schools. And already, they’re being stamped out.

Republican political leaders in all but a few states (44 total) have since 2021 proposed legislation or policies restricting lessons about race and racism in the United States – what many inaccurately decry as a graduate-level framework called “critical race theory.” As of June, 18 states had such laws on the books, according to an Education Week analysis.

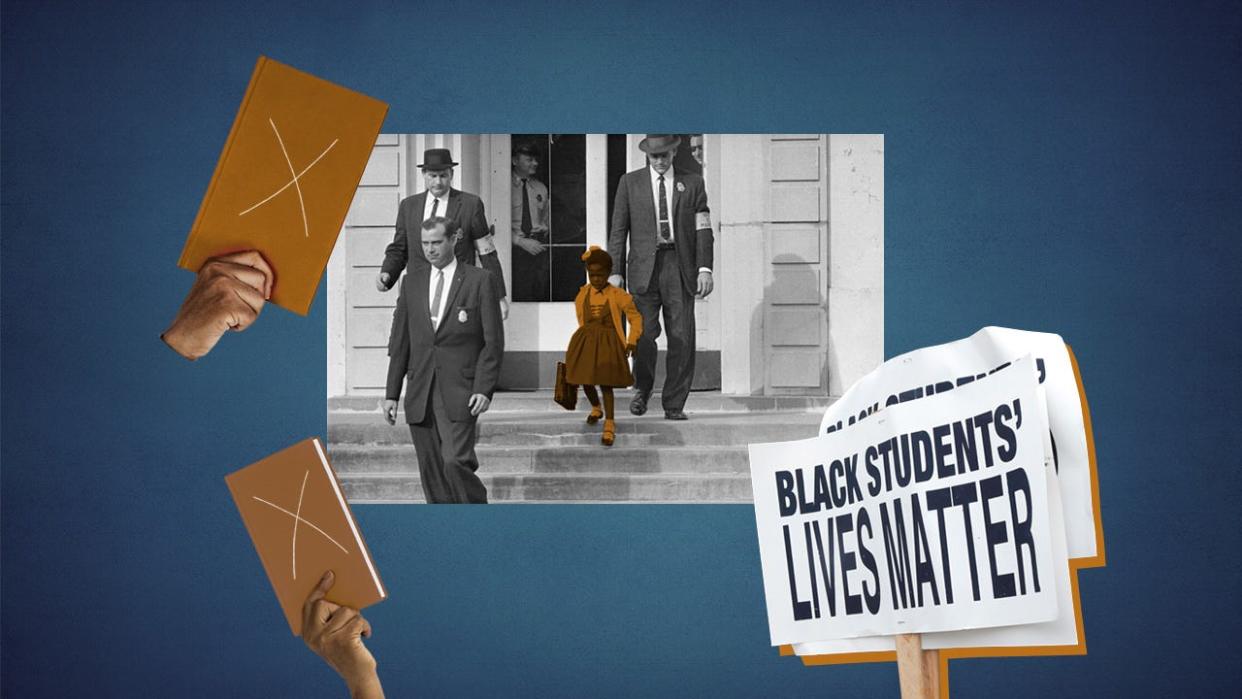

The classroom effects have been immediate. Civil rights activists both dead and alive have had their stories erased from social studies classes in the name of protecting children’s innocence and comfort. Books by Black – and especially LGBTQ Black – authors have been pulled off classroom and library shelves on the grounds that their perspectives are, to borrow a word found in many of the laws, “divisive.”

Florida called for a ban on the Advanced Placement African American course Holley, a young Black man and soon-to-be freshman at Georgia Institute of Technology, said taught him what his “ancestors were capable of and convinced me that I am capable of great things as well.” The move was followed by resistance to the course in other Republican-led states.

Here are a few moments from the past year that show how education has changed in the anti-CRT era – whether by sanitizing the uncomfortable truths or by fighting for those truths to come out.

Disney movie about school integration deemed ‘inappropriate’ for young children

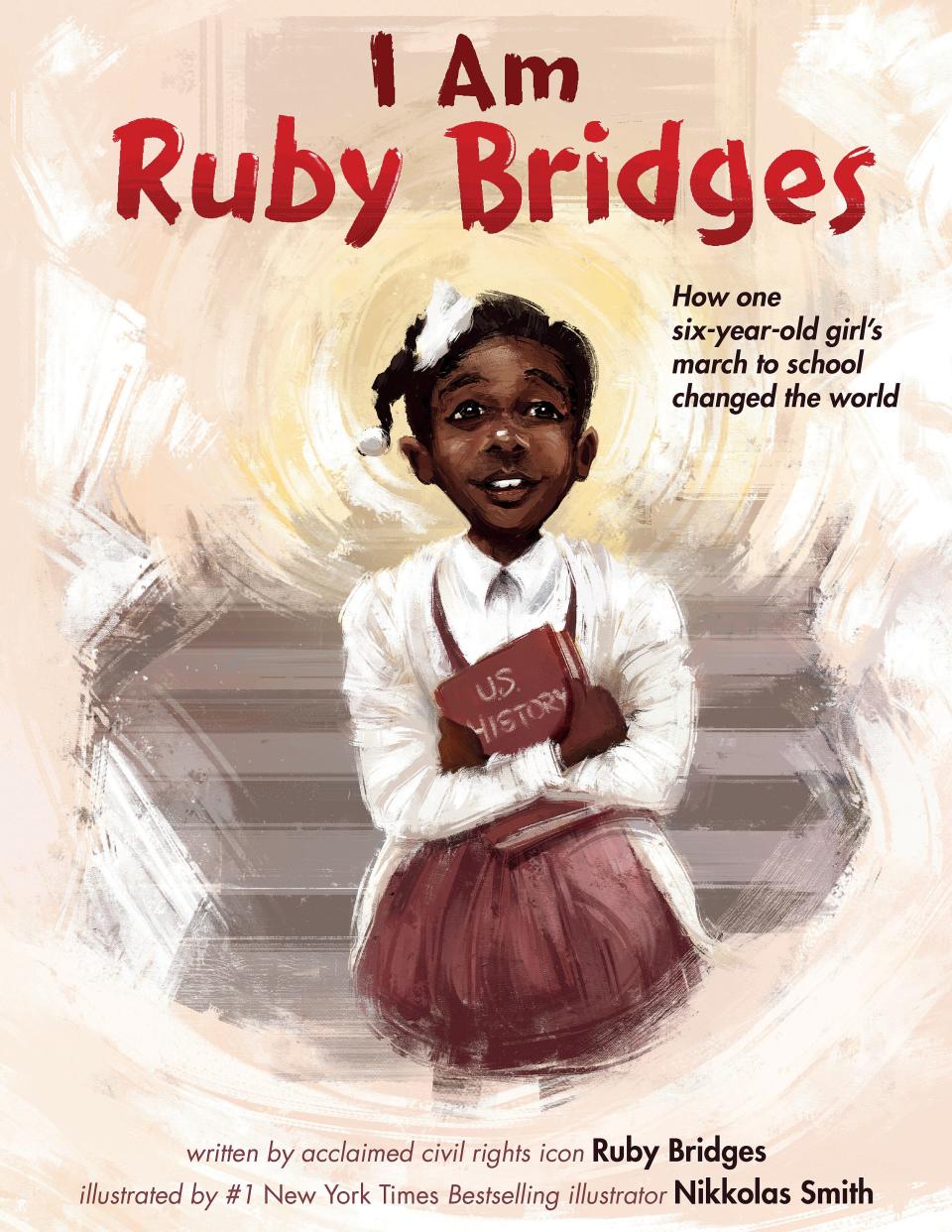

Earlier this year, a Florida school district banned the Disney movie “Ruby Bridges” after a parent complained its themes were inappropriate for young children.

The 1998 movie, about the first Black child to desegregate an all-white school in Louisiana in 1960, explores “the true ugliness of racism” but also the love she received from her mom and dad and her “heroic struggle for a better education.”

The parent in March filed a complaint, citing scenes of white people threatening 6-year-old Ruby as she entered a school. As the Tampa Bay Times reported, the parent argued that scene could teach white students to hate Black people. The school temporarily banned the movie in response.

Shortly after the fallout, the state education commissioner, an appointee of Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, named Bridges’ “I am Ruby Bridges” children’s book as his recommended read of the month for children in grades kindergarten through two. But other works authored by Bridges have been the target of “divisive concepts” claims in states such as Texas and Tennessee, too.

“If you’re banning my books because they’re too truthful, then why don’t we start having a conversation about the books that we force our young people to study, like the textbooks we know omit so much of the truth?” Bridges told reporters earlier this year.

Toni Morrison, Ta-Nehisi Coates – Black authors banned from classrooms

Bridges, of course, is hardly the only Black author whose books were removed from learning spaces this year over concerns of age-appropriateness or discomfort or morality.

The late Toni Morrison, the first Black woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, had her books removed in districts ranging from Spotsylvania, Virginia, to Davis County, Utah.

In Chapin, South Carolina, an Advanced Placement (AP) Language teacher was forced to remove MacArthur Genius Ta-Nehisi Coates’s “Between the World and Me,” a widely acclaimed memoir about race, identity and Black experience, from a unit meant to prepare her students for their upcoming exam. A couple students wrote to the school board saying the lesson made them feel “ashamed to be Caucasian” and alluding to a South Carolina state law that bans the teaching of “divisive concepts.”

Sapphire’s “Push,” which inspired the Oscar-winning movie “Precious,” was banned a dozen times – most within the span of a few months – this past school year. Complaints typically pointed to its descriptions of sexual and emotional abuse.

Black and LGBTQ authors and books about race, racism and queer identities have been disproportionately affected in the book bans documented by PEN America, a free speech and literary organization, since fall 2021.

The trends only became more pronounced in the past year. Nearly a third (30%) of the unique titles removed from school districts in fall 2022, for example, are books about race, racism, or feature characters of color.

The battle over AP African American Studies

Florida was this year’s hot spot in the culture wars over how and what to teach, with much of the debate centering on the same AP African American Studies course Holley took one state over in Atlanta.

Holley’s school was the only one in Georgia – and one of just 60 nationally – to pilot it last year. Hundreds more are participating this upcoming school year. The first exams will be administered in spring 2024.

In January, Florida education department officials announced the state would be rejecting aspects of the course, saying it violated state law and was “significantly” lacking in educational value. While the letter didn’t specify which law, DeSantis last year signed the Stop W.O.K.E. Act, which among other things restricts discussions about race and LGBTQ+ issues in classrooms.

The College Board, the organization that runs the AP program, soon thereafter issued a revised curriculum that excluded portions highlighted by the DeSantis administration. Concepts such as “intersectionality” were removed, as were works by authors associated with the critical race theory framework. Coates, the author removed from an AP Language classroom in South Carolina, was also scrubbed from course material.

Leaked correspondence revealed the College Board and Florida had been in discussions for months. Backlash against the College Board was swift, with critics accusing the organization of capitulating to political pressures, and the College Board later conceding it had erred in its handling of changes to the class.

Despite it still being in the pilot phase, and despite it being banned in Florida, demand for the AP course has soared nationally. New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy, for example, announced the state would be expanding the program to more than two dozen schools. According to the College Board, 800 schools will be offering AP course to 16,000 students this fall.

Meanwhile, the resistance continues. Arkansas's education department in August, just ahead of the school year's start, announced students in the state cannot earn high school credit for the course.

Bringing it back to Black joy

Kim Tate, a fifth-grade dual-language teacher in the Chicago area, years ago began developing curricula based on The 1619 Project, the New York Times investigation by Nikole Hannah-Jones into slavery’s role in the founding of the United States.

Early on in the pandemic, her students still learning entirely through their computers, Tate witnessed how fixated they became on the murder of George Floyd. The children, now at an age where they were really starting to think critically about things, were desperate to understand how someone could be so dehumanized. They started to make connections. People were also dehumanized during the Holocaust. What if this were my dad? My uncle was violently detained once, too – at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“It really, really impacted them. In a really powerful way. And I realized I needed to tap into that. This is an important opportunity that I can’t miss,” Tate said. “One of the things that really hit home for me: If the content we are teaching isn’t relevant to the lives our students are living, they don’t want any part of it.”

This revelation brought her to the 1619 Project’s resources, including a children’s book whose protagonist struggles to track down her ancestry because those forefathers were enslaved. But the story highlights the love in her life, and the pride.

“I think that’s missing from a lot of the teaching of our history – the aspirational part,” Tate said.

African American history is as much about perseverance as it is about pain, yet efforts to remove uncomfortable narratives strip out both. And that, Tate said, is perhaps what’s most pernicious about the anti-CRT movement.

“There have to be some uplifting aspects, something that leaves the learner with hope,” Tate said. “Something that leaves them with a baton that says, ‘Yes, the work continues.’”

Illinois recently became the first state in the country to pass a law prohibiting bans on books.

What would MLK Jr. do?

James McCarty, a theologian, ethicist and professor of conflict transformation at Boston University who has written about and researched King extensively, said lessons about the civil rights hero and his era have been sanitized for years.

But the growing boldness of efforts to whitewash lessons is something McCarty said he hasn’t seen before. Certain people are seeking to remove everything that may cause discomfort, he said, yet “a good educational practice is to make people uncomfortable.”

If King were around today, McCarty theorized, the civil rights hero would go beyond “making moral appeals.” Instead, he would urge educators and students to disrupt.

“King lived a life of confrontation – always with the goal of 'beloved community' at the end of the day,” McCarty said. “I don’t think King would say, ‘I’ve got a dream.’ I think he’d say, ‘Get organized.’”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Florida's Black History attacks form part of larger nationwide assault