Candidates propose expanding the 'war on terror' to counter the real threat: White supremacists

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

White supremacist violence is on the rise. Before an attack at an El Paso, Texas, Walmart left 22 mostly Latinx shoppers dead earlier this month, there was a shooting at a synagogue in California in April and, before that, the murders of 11 worshipers at a Pittsburgh synagogue in 2018. There was a fatal clash at a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017, a mass killing of African-Americans at a prayer meeting in a church in Charleston, S.C., in 2015 and six murdered at a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wis., in 2012.

Before the El Paso attack, the FBI in July said the bureau had recorded about 90 domestic terrorism arrests in the previous nine months, compared with about 100 international terrorism arrests. And since the El Paso shooting, which was declared an act of “domestic terrorism" by the Justice Department, the FBI has thwarted seven mass shootings, including attacks planned by alleged white supremacists.

But those arrested are unlikely to be designated as domestic terrorists or face any federal terrorism-related charges.

Weeks after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the USA Patriot Act of 2001 was passed in an effort to provide law enforcement more power to detect and deter terrorism. The law expanded the category of federal crimes to cover more acts of foreign terrorism, but sparked controversy over domestic surveillance when it was revealed that intelligence agencies had been authorized to collect metadata, including phone records, from American citizens.

Under the Patriot Act, domestic terrorism is defined as an act “dangerous to human life” that violates federal or state criminal law and intends to intimidate or coerce civilians, influence government policy through intimidation or coercion, or affect government conduct by mass destruction, assassination or kidnapping within the United States. Broadly speaking, a chargeable offense under the act requires a connection to a foreign terrorist organization, use of a weapon of mass destruction or an attack on a U.S. government official or property; it does not cover attacks motivated by extremist ideologies using guns or vehicles.

If bombs are involved, offenders can be charged under a small umbrella of terrorism-related criminal offenses — though not simply “domestic terrorism.” Attacks with firearms are, of course, prosecutable under existing state and federal statutes, but some law enforcement officials believe additional tools are needed to investigate and prosecute homegrown mass attacks.

The FBI considers crimes committed in furtherance of racially motivated violent extremism, antigovernment/antiauthority extremism, animal rights/environmental extremism and abortion extremism “domestic terrorism threats.”

A few years after 9/11, the Terrorist Threat Integration Center, now the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), was established in response to terrorism overseas, specifically excluding “purely domestic counterterrorism information.” While the center does not collect information or carry out operations, it analyzes data from partners overseas and within the U.S.

A recent analysis by the Intercept found that “268 right-wing extremists prosecuted in federal court since 9/11 were allegedly involved in crimes that appear to have met the legal definition of domestic terrorism. Yet the Justice Department applied anti-terrorism laws against only 34 of them, compared to more than 500 alleged international terrorists.”

Under existing law, a charge of terrorism requires showing that someone provided material support or resources, or “any property, tangible or intangible, or service,” such as money, training, personnel or weapons, to officially designated foreign terrorist groups for terrorism-related crimes. This material-support law can be used broadly by law enforcement, allowing it to detain people suspected of aiding a would-be terrorist attack or prosecute them under nearly 50 proscribed offenses, including using weapons of mass destruction, bombing government buildings or killing government employees.

But there is currently no statute prohibiting someone from providing material support to violent white supremacist extremists within U.S. borders.

Over the past several years, as hate crimes, a category that can overlap with white supremacist attacks, have steadily increased, lawmakers have called on the FBI and Justice Department to track, assess and prosecute homegrown terrorism and provide data on incidents, investigations, convictions and weapons recoveries.

Immediately after the El Paso mass shooting, Democratic candidates condemned white supremacy and put forth proposals to prevent future acts of white nationalist violence. They largely built on past proposals for gun control and prioritizing white supremacist terrorism within law enforcement.

Sen. Kamala Harris said President Trump has “played coy with white supremacists and shifted resources away from countering violent white supremacist threats.” She has said she would commit $2 billion over 10 years to investigate, disrupt and prosecute domestic terrorists.

Harris would “instruct NCTC to devote more resources to analyzing and preventing global white nationalist terrorism” and seek to expand the center’s mission to include domestic terrorism, allowing the NCTC to work with other federal agencies to combat the problem.

Her plan would allow federal courts to issue new “Domestic Terrorism Prevention Orders” to temporarily seize firearms of a “suspected terrorist or individual who may imminently perpetrate a hate crime” and require background checks on online gun sales platforms “to disarm domestic terrorists and hate crime perpetrators before they are able to carry out their attacks.”

Because social media platforms have produced a new environment for promoting extremist violence, Harris said she would make it a priority for the FBI to better monitor white nationalists online, “consistent with well-established legal requirements and civil liberties protections.”

Months before releasing his plan, Sen. Cory Booker co-sponsored the Domestic Terrorism Prevention Act, which called on the Justice Department to assess the “threat posed by white supremacists” and to “provide transparency through a public quantitative analysis of domestic terrorism-related assessments, investigations, incidents, arrests, indictments, prosecutions, convictions and weapons recoveries.”

“While white supremacy is not a new phenomenon in America, it’s incredibly troubling the way the movement has been emboldened, and the administration’s efforts to obfuscate the data on these terrorist incidents simply defies logic,” Booker told Yahoo News.

Alleged white supremacists were responsible for all race-based domestic terrorism incidents in 2018, according to a government document distributed earlier this year to state, local and federal law enforcement, but the Trump administration’s Justice Department has been unable or unwilling to provide data to Congress on white supremacist domestic terrorism, Yahoo News recently reported.

Booker’s plan calls for improved data collection on white supremacist violence and for federal law enforcement to give such attacks equal priority with international terrorism, requiring a specific “white supremacist” designation within the FBI’s domestic terror categories. A Booker administration would create a White House Office on Hate Crimes and White Supremacist Violence, an advisory group of “community stakeholders” affected by hate crimes that would share information with the White House, the FBI, the Justice Department and Homeland Security.

Former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke was among the loudest critics of white supremacy rhetoric after the mass shooting in his hometown of El Paso.

His plan to combat white supremacist violence focuses on tighter gun laws and stemming the spread of hateful rhetoric that leads to violence.

?“Congress’s failure to act has resulted in a democracy that is unwilling to confront an epidemic of gun violence,” O’Rourke said when unveiling his program. “It’s time for those in positions of public trust to stand up, tell the truth and offer bold solutions without fear of political ramifications so we can finally start making progress and saving lives.”

He called for a ban on military-style assault weapons, instituting federal red-flag laws that would allow law enforcement “to petition in federal courts to have weapons removed from those who present a danger to themselves or others, including white nationalists planning to perpetrate a hate crime,” and a national licensing program.

In light of posts by the alleged El Paso attacker to the online messaging board 8chan, O’Rourke’s plan would also require internet platforms to block terrorist content online. He called on Congress to amend the Communications Decency Act’s Section 230 — which protects internet companies from being held responsible for their users’ actions — to hold domain name servers and social media platforms “liable where they are found to knowingly promote content that incites violence.”

Since 9/11, counterterrorism has been a top priority not only for the FBI but also for Americans, topping education, the economy and health care costs, according to the Pew Research Center. But proposals to combat domestic terrorism have been fraught with debates over civil liberties, oversight and transparency.

While the FBI Agents Association has urged Congress to make domestic terrorism a federal crime, civil liberties groups worry about greatly expanding the use of such techniques as mass surveillance and undercover sting operations, which are now mostly employed against international terrorists. A law intended to curb white supremacist violence could also be used against minorities, they warn.

“So many of the proposals that are being made now, while well intentioned, ignore the multiple ways in which domestic terrorism authorities disproportionately target and harm black and brown people and Muslims who are subjected to discriminatory and unfair surveillance investigations and prosecutions,” Hina Shamsi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Security Project, told Yahoo News.

“There are multiple examples, whether we're talking about an inflammatory and made-up category of ‘black identity extremists’ to unjustified focus on environmental activists and pro-choice activists to those demonstrating against family separation policies and other forms of dissent,” she said. “There is an entire so-called domestic terrorism framework that encompasses authorities, task forces, fusion centers that has resulted in unjustified and unmerited focus on communities of color and those who dissent against government policies.”

Shamsi urged that policymakers require law enforcement to provide more public data on how it has used resources to prioritize addressing white supremacist violence instead of putting forth “purported solutions that would undermine the rights of the communities of color that white supremacist violence attacks.”

“If NCTC starts to look at white supremacy, hate crimes … I would be very cautious about that,” Joe Augustyn, former deputy associate director of central intelligence for homeland security, told Yahoo News. “To me, it’s opening Pandora’s box.”

Instead of establishing a domestic terrorist designation that would create First Amendment problems, Mary McCord, a former Department of Justice official who served as acting assistant attorney general for national security, called for “creating an offense that would apply to the most common means of committing terrorist acts regardless of ideology, which is mass shootings.”

“Because right now there’s no terrorism affront that applies to terrorism committed with a firearm unless it’s connected to a foreign terrorist organization,” she told Yahoo News.

McCord said she understands “the distrust for law enforcement that many people in vulnerable communities, communities of color and others have felt, including Muslim American communities who have felt like they’ve been somewhat targeted [by] counterterrorism efforts ever since 9/11.” But prevention, she said, is really the only way to stop domestic terrorist attacks.

“We’re talking about crime prevention,” McCord said, “and it’s a matter of making sure that there’s enough reporting about how the FBI is investigating these things, how it’s using its tools, that there’s transparency to make sure that it’s really using them against the threat.”

Michael German, a former FBI agent and current fellow with the Brennan Center for Justice, pointed to the 200 protesters at Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration who were arrested and charged with felonies as an example of the “valid fear” among Americans who oppose giving law enforcement “broad authorities” to aggressively use its domestic terrorism powers.

“When you’re asking for this broad authority, they’re not asking for some narrowly focused law that will somehow enhance their power to go after white supremacists or to compel the Justice Department to change its priorities and focus on hate crimes,” he told Yahoo News. “They’re asking for a broad authority that can be used to target anyone they choose, and the groups they’ve chosen in the past to focus on tend to be groups that are protesting government policy rather than groups that are engaged in deadly violence.”

German believes more information from the Justice Department is needed to formulate effective policy.

“What we need to do is focus on violence prevention,” he added. “And that, of course, requires the conversation about gun control, social services to address people who are having some kind of personal crisis, and many other tactics that will make all our communities safer.”

But supporters of a domestic terrorist designation that would include white supremacists are skeptical about alternative strategies that don’t empower federal institutions to prevent future attacks.

As Clint Watts, a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute and former executive officer of the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, put it, “If you can’t look at anything, you’re not going to see anything. And if you can’t see anything, you can’t do anything.”

Without a designation process behind domestic terrorism, whether it’s a law or just a rule, Watts argued, law enforcement cannot be proactive in preventing future attacks. “You’re just saying wait till a bunch of people get killed and then go look at what happened,” he told Yahoo News.

“How on earth can you investigate preemptively if [suspects] can buy weapons legally, if they can work online and you’re not allowed to look at anything they say in terms of their speech or [if they are] connected with a larger ideological movement? The FBI director has to have the ability to designate a case based on inspired extremism.”

Watts said the FBI already knows what to do with white supremacist terrorists, but “you can’t touch the domestics," he said. "That’s a constituency. White supremacists vote. Al-Qaida and ISIS don’t. It’s stark, [but] that’s where this deliberation comes down to: Where’s the line towards violence?”

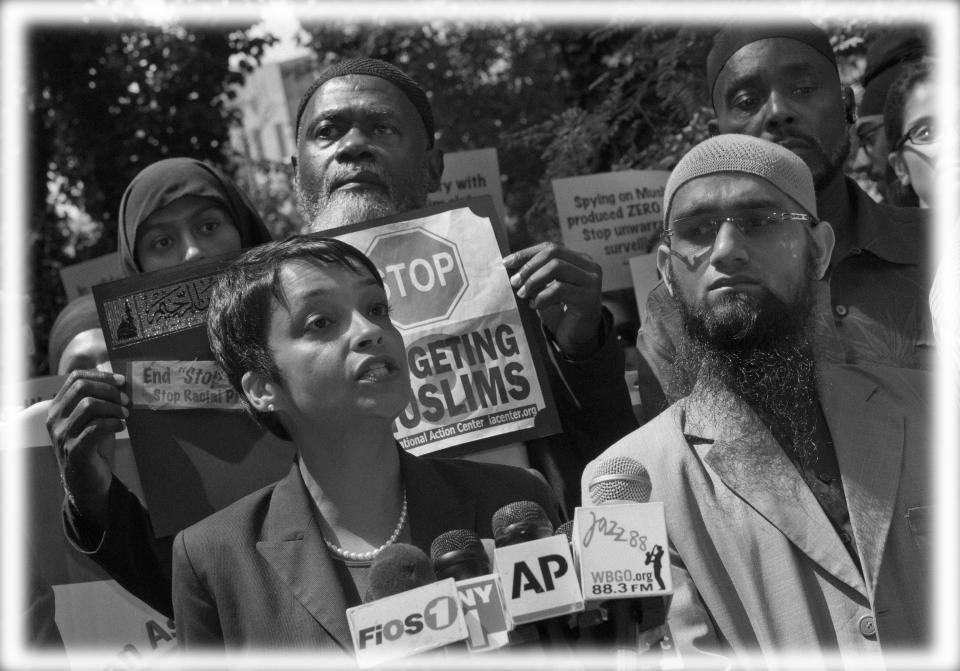

Civil liberties advocates like Shamsi worry that “the wrong lessons from discriminatory and unfair terrorism approaches that have led to discriminatory and unfair investigations, prosecutions, watch list, surveillance and even more broadly indefinite detention, and stigmatizing of mental illness” could be reapplied in domestic cases such as the NYPD’s illegal surveillance of Muslims at mosques, schools and restaurants that began in 2001.

“White supremacist violence can and must be addressed,” Shamsi said, but “with responsible rights-respecting policies that safeguards communities of color and those who dissent against government policies.”

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News: