In debate over political speech, pastors say they fear the IRS ‘pulpit police’

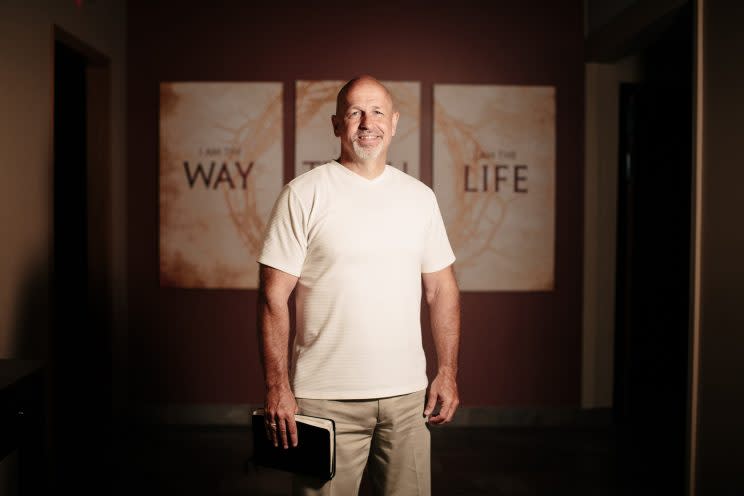

As Washington struggles to come up with a new health care insurance system, Jim Garlow believes he has a solution, but he worries about sharing it publicly — simply because he is a pastor.

Garlow, lead pastor of Skyline Church in La Mesa, Calif., blames a provision in the federal tax code known as the Johnson Amendment for what he calls the “self-censorship” of pastors across the nation. It forbids 501(c)(3) nonprofits, a category that includes most of the nation’s churches and other charitable organizations, from getting directly involved in elections. (It is not a criminal statute; violators face only the loss of the organization’s tax-exempt status.) Many hail it as a protector of Thomas Jefferson’s famous “wall of separation” between church and state, but to Garlow and other outspoken pastors around the nation, it is an unconstitutional restriction on free speech.

“Morally and theologically, I don’t believe the government has any role in dictating what a church or faith community says or does not say in the pulpit at all,” Garlow said. “It a matter of conscience, based on that particular pastor and that congregation.”

The amendment only explicitly prohibits outright endorsements or opposition of candidates running for office, but Garlow, along with thousands of other pastors and advocacy groups, fears that speaking out on hot-button political issues, such as health care or immigration, could also violate the amendment, causing their organizations to lose their tax-exempt status.

As a result, Garlow calls the IRS “the pulpit police.”

The picture that suggests — of federal agents surreptitiously monitoring sermons — conflicts with reality. The amendment has been enforced only once in the six decades it has been on the books, against a church that took out a full-page newspaper ad against Bill Clinton.

Yet Garlow still sees reason for concern. “Now where the ambiguity sets in is even the IRS has been a bit challenged by explaining what the Johnson Amendment is,” he said. “For example, if one candidate is pro-abortion and the other candidate is pro-life and you say, ‘Christians should vote pro-life,’ and you don’t even mention the names of the candidates, is that not in fact a de facto endorsement? I would contend it probably is.”

That consideration has not, obviously, prevented churches from taking stands on abortion or other contentious political questions. Garlow’s concerns seem mostly theoretical. But as long as the amendment remains in effect, future administrations could interpret it more strictly.

Aside from the hypothetical practical consequences, Garlow sees advocating against the Johnson Amendment as a moral responsibility. To him, preventing religious leaders from joining the national discourse on political issues is not only a violation of the First Amendment, but it also robs the nation of unconventional viewpoints that could make useful contributions to solving the country’s problems.

“If that were to occur, we’d have an enormous reduction in human suffering and an enormous reduction in poverty,” Garlow said. “Every inner city that’s hurting is there because of public policies based on faulty principles. Those principles could be turned.”

“The pulpits of America can save America from disaster,” Garlow said. “We have a colossal economic failure of a health care plan that was doomed at failure from its outset, and we’re going to have the same again unless we can realize that health care is an individual responsibility; No. 2, it’s a family responsibility; and No. 3, the Scripture says care for one another.”

He believes, based on his own religious convictions, that health care sharing programs such as MedShare and Liberty Healthcare Share, where members make monthly contributions to cover each other’s medical care costs, would be less expensive and more stable than government-subsidized markets. He also believes that it is his right to urge his congregation to vote for candidates who would fight for similar programs in Congress.

Garlow says his goal is not to use his 2,000-member church as a political machine to sway elections. He believes that advising his congregation on the issues of the day is a vital part of his role in his church, which is to counsel parishioners on how best to live their lives within their religious beliefs.

A bill to overturn the amendment, the Free Speech Fairness Act, has been introduced in Congress. It would lift the restrictions on political speech by pastors, but would not permit churches to use tax-exempt funds for political activities such as purchasing advertising. But some experts on civil liberties are concerned about tampering with the status quo.

“Not having the Johnson Amendment would … push religion to become more politicized and vulnerable to co-opting by partisan forces than it already is,” said Mark Chaves, Duke University professor of sociology, religious studies, and divinity.

Chaves believes that the amendment’s ambiguities leave room for pastors to provide the moral guidance that their congregations rely on.

“Congregations already have ways to make it clear which candidates they support or not through slanted voter guides and whatnot,” Chaves said. “[Repealing the Johnson Amendment] would risk further politicizing religion in America, and I think that’s why I personally think it would be a very bad idea to encourage this further. It’s already politicized, and I think it would be a bad idea to push it further in that direction.”

Others, like Americans United for the Separation of Church and State, are less worried about what the expanded political freedoms would mean for churches and the 37 percent of Americans who fill their pews weekly, but on the impact such legislation could have on the USA’s famous “wall of separation between the church and state.”

The rule, however, was not written with the First Amendment in mind. Most scholars believe the measure, introduced by future President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1954 while he was a senator from Texas, was designed to silence Facts Forum and the Committee for Constitutional Government, two vocal nonprofits financing an opponent in his Senate reelection bid.

Johnson’s chief aide at the time, George Reedy, later stated that the amendment wasn’t aimed at churches, and Johnson never intended that outcome. Religious organizations were affected because they share the same tax-exempt status as the organizations Johnson disliked.

For this reason, the Alliance Defending Freedom, a conservative advocacy group, has been fighting to challenge the amendment’s constitutionality in court for nearly a decade. Every year, thousands of pastors preach explicitly political sermons and send recordings of them to the IRS hoping to provoke an audit they could challenge in court. So far, the IRS has not taken the bait.

“What we have always said is, it’s the job of the pastor to decide what’s said in the pulpit, not the IRS,” said ADF’s senior counsel, Erik Stanley. “We have never placed any content controls on what’s said from the pulpit. All we are advocating for is the right of the pastor to determine what is said in the pulpit and what guidance he should give his congregation.”

“Regardless of the IRS’ posture of enforcement, the government has to be clear that a pastor can speak freely from the pulpit, and that’s way the statute itself needs to go,” Stanley said.

Despite their lack of success, Stanley remains hopeful. President Trump said in February that he will “totally destroy” the Johnson Amendment.

“Among those freedoms is the right to worship according to our own beliefs,” Trump said at the National Prayer Breakfast. “That is why I will get rid of and totally destroy the Johnson Amendment and allow our representatives of faith to speak freely and without fear of retribution.”

Trump signed a religious freedom executive order in May that did little to solve the problem, according to Stanley and Garlow. The Free Speech Fairness Act will likely not even come up for a vote this year, according to Stanley. Some lawmakers, however, are attempting to work around it, adding language to a federal spending bill that would require a Johnson Amendment investigation to be greenlighted by the IRS commissioner, who would then be required to consult Congress.

But for now, the amendment remains law. That, however, hasn’t stopped some pastors from discussing politics from the pulpit as they see fit.

“I think the church has always had a responsibility to speak to those in power and to articulate God’s view on these important issues,” said Ron Johnson, pastor of Living Stones Church in Crown Point, Ind. “We believe that the Bible is the Word of God, and we believe again that we have a moral responsibility to help shape public policy and that the church should not be muzzled, should not be silenced.”

Johnson says he “pretty much ignores” the amendment himself. He made headlines in 2008 when he was quoted in the Washington Post saying that Christians who planned to vote for President Obama displayed “severe moral schizophrenia.”

He regards this as an example of the church’s participation in public discourse, but not a specifically political statement: “I think some people think that if the Johnson Amendment is somehow removed, our churches will become political action committees,” Johnson said. “No, that is not going to happen. You know, we don’t have any desire to somehow turn the church into a political institution, as some on the other side of the issue may be accusing. What I see happening is acknowledging the freedom that churches had from the very beginning of this country to talk about important public issues and to have our say, and to have our voice and to be able to be a part of public discussion and discourse.”

Not all Christians are eager for their pastors to raise their voices on government issues, however. In a 2016 poll, Pew Research Center found that 47 percent of Americans don’t think churches should publicly express their views on political and social issues. Chaves, who runs a national survey of church congregations, also estimates that pastors such as Johnson and Garlow are in the minority.

To Garlow, neither the opinions of his critics or skeptical Christians matter. He firmly believes that the United States will be better off allowing more voices into the political arena.

Johnson agrees.

“The church should not be told [that politics are] none of our business,” Johnson said. “It is our business.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Trump’s Paris trip is poised to give a clear win to France’s Macron

Even some in White House are frustrated by the stonewalling on Donald Jr.’s meeting

White House launches preemptive strike on CBO, anticipating report on health care bill

Photos: In Mosul, the war is never over, even when the shooting stops