If the problem is mental illness, these candidates have a plan for that

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

While data suggests that one in five adults deals with mental illness, many Americans feel that their insurance providers offer too thin and, in some cases, no coverage to meet their demanding and sometimes debilitating health concerns — a conundrum that forces patients to pursue pricey out-of-network care. A 2017 study conducted by the consulting firm Milliman found several discrepancies in the way both patients and doctors who work within the realm of mental health were treated; for example, in 2015, patients were four to six times more likely to be provided behavioral care out of network than in network.

Lack of treatment has a serious impact on consumers’ wallets — the American Journal of Psychiatry estimated back in 2008 that serious mental illness cost the country $193.2 billion a year in lost earnings. And federal funding wasn’t keeping up the pace, according to Time magazine, which reported that merely 6.2 percent of total U.S. health care funding in 2008 was allocated to mental health treatment. Lawmakers attempted to reconcile the discrepancy in the same year with the bipartisan Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) — an extension of similar legislation passed in 1996 — as well as a rider tacked onto the Troubled Asset Relief Program.

“Each year the economic cost of untreated mental illness is staggering — over $100 billion on untreated mental health disorders and $400 billion on addiction disorders,” Rep. John Sullivan, R-Okla., told Time. “Our country cannot afford to continue losing $500 billion a year to these treatable diseases.”

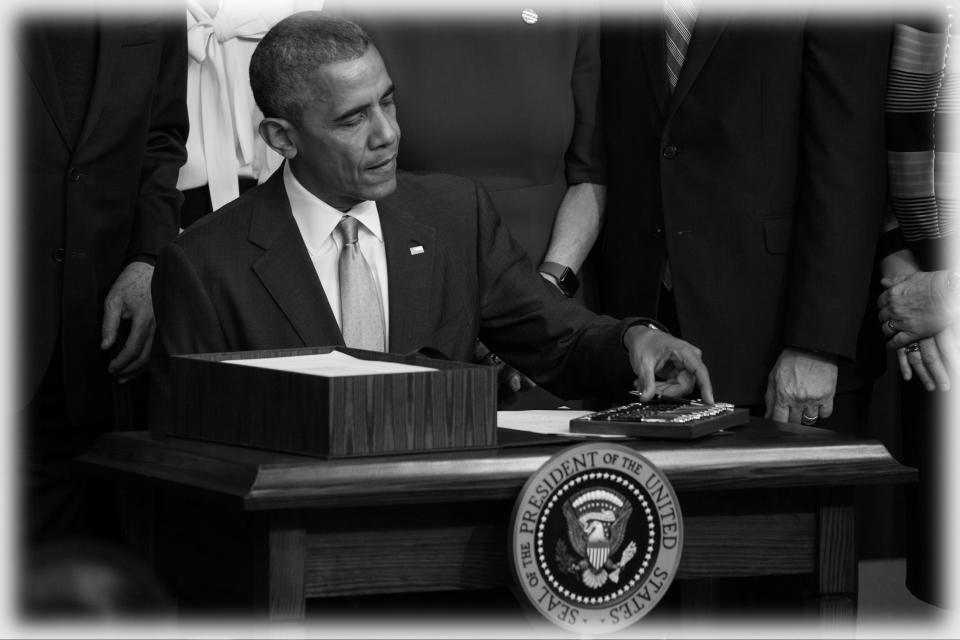

In layman’s terms, the MHPAEA prohibits insurance providers from imposing what many view as unfair benefit limitations on recipients dealing with mental health or substance abuse disorders. Obama-era policies advanced the ball a bit, with provisions in the Affordable Care Act building on the MHPAEA by applying regulations to individual — rather than group — plans, though state governments also play a hand in enforcing or expanding the legislation.

Still, despite provisions, the cost of treating mental disorders can be overwhelming, as access to necessary services shrinks year to year; a special report from USA Today discovered that states had slashed $5 billion in mental health services from 2009 to 2012. To make matters more dire, those who needed in-patient psychiatric care had fewer places to stay, as at least 4,500 public psychiatric hospital beds were eliminated in the same period. As the size of provider networks and resources has continued to shrink, the rate of suicide has ticked up: From 1999 to 2016, the national suicide rate increased more than 25 percent.

Now the country deals with stigma permeating conversations about mental health, and with the national cost of the crisis hovering around $444 billion a year, presidential candidates have put forth several proposals to combat high premiums and coverage black holes.

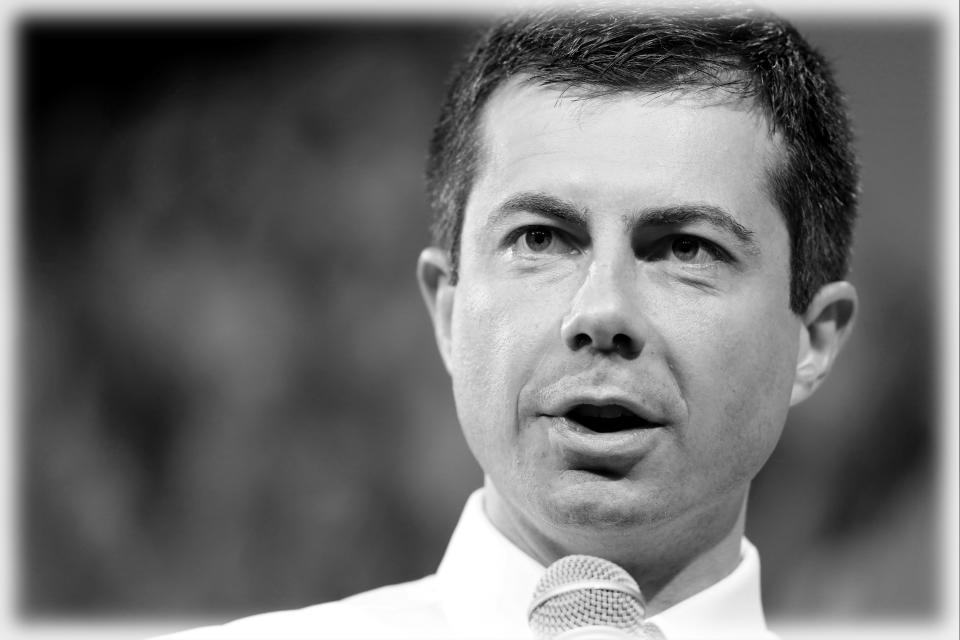

South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg released an 18-page plan in August, which, in part, aims to cover mental health treatment for at least three-quarters of Americans in need of it by the end of his first term, along with a $10 billion annual grant to communities to address the issues in their localities.

“For years, politicians in Washington have claimed to prioritize mental health care while slashing funding for treatment and ignoring America’s growing addiction and mental health crisis,” Buttigieg said in a statement. “That neglect must end. Our plan breaks down the barriers around mental health and builds up a sense of belonging that will help millions of suffering Americans heal.”

Buttigieg’s plan also addresses societal stigma that would be talked about in the classroom; his proposal mandates that public schools teach mental health first aid courses, train to recognize common symptoms, understand treatment options and provide advice on how to intervene and help those affected. Former Vice President Joe Biden has a similar proposal, albeit one that relies on more traditional forms of care. As part of his education package, Biden aims to double the number of psychiatrists, nurses and other mental health professionals in schools.

“We need mental health professionals in our schools to help provide quality mental health care, but we don’t have nearly enough,” Biden’s campaign says on its website. “The current school psychologist to student ratio in this country is roughly 1,400 to 1, while experts say it should be at most 700 to 1.” (Presumably the intended meaning was “student to school psychologist ratio.”) “That’s a gap of about 35,000 to 60,000 school psychologists. Teachers too often end up having to fill the gap, taking away from their time focusing on teaching.”

Rep. Tim Ryan, D-Ohio, poses a similar solution to tackling mental health as part of his education plan with mandated mental health counselors in each public school, believing the key to comprehensive treatment starts early, within the classroom. In a statement, Ryan framed the issue in terms of preventing gun violence, though many experts agree that those suffering from mental illness are more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violence.

“Seventy-three percent of [school shooters] feel shamed, traumatized or bullied. We need to make sure that these kids feel connected to the school. That means a mental health counselor in every single school in the United States,” Ryan said.

The Medicare for All plans of both Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and California Sen. Kamala Harris aim to take pressure off consumers’ wallets, which, in both candidates’ eyes, would free up money for lifesaving mental health treatments. Harris’s plan would cover “all necessary services,” which includes hospital visits, substance use disorder treatments, doctors’ visits and the like.

“Under my Medicare for All plan, we will also expand the program to include other benefits Americans desperately need that will save money in the long run, such as an expanded mental health program including telehealth and easier access to early diagnosis and treatment, and innovative patient programs to help people identify the right doctor and understand how to navigate the health system,” Harris said in a statement.

Sanders’s plan echoes lines found often in his stump speeches: Mandating lower costs for over-the-counter drugs will save lives. Through the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Act and the Prescription Drug Price Relief Act, Medicare would bargain with leading drug companies to push down costs while mandating that costs be pegged to the average price across Canadian, British, French, German and Japanese markets.

Recent back-to-back mass shootings have propelled mental health back into the public conversation. When pressed by reporters on whether he was going to urge Congress for more stringent gun laws, President Trump demurred, instead insisting that “mental illness and hatred pulls the trigger, not the gun.” Trump’s remarks are part of a common deflection, echoed by many White House officials and Republicans with strong ties to the gun lobby, regarded by critics as a political strategy to frame post-shooting conversations away from gun reform and toward larger societal implications like the impacts of mental health and video games. Experts agree that neither is a major factor.

And while Trump calls for reform, his administration’s policy tells another story. CNBC reported that the White House’s rollback of Obama-era policies now allows individuals to stay on short-term health care plans that often write off those with mental health issues as a preexisting condition. That, coupled with hardened requirements to quality for stateside mental health treatment, places those desperate for coverage in a true bind.

Lawmakers are set to reconvene after August recess in the coming weeks and will likely debate bipartisan legislation teed up by Sens. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., which would allocate more money to local police and other authorities to “hire and consult with mental health professionals,” though it stops short of reallocating funding for mental health resources, such as psychiatric hospitals. Even the future of this lean version of mental health legislation is uncertain; Axios reported that if the parties can’t reach consensus on a measure addressing guns and mental health by September, it’s unlikely any bill will pass until after the 2020 election, leaving the fate of many ill Americans up in the air.

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News:

Document reveals the FBI is tracking border protest groups as extremist organizations

How a secret Dutch mole aided the U.S.-Israeli Stuxnet cyberattack on Iran

Felix Sater: Trump wanted to reveal my secret CIA, FBI work during the campaign

PHOTOS: Hurricane Dorian’s destruction of the Bahamas captured from above