Dems have a plan for that: Medicare for All, and all the rest of them

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

The American health care system is currently a hodgepodge of ideas, including Medicare (covering those over 65), Medicaid (a state-managed system covering low-income Americans) and private insurance supplied by employers or purchased on the Obamacare exchanges. The result is extremely expensive care with 28 million people without coverage, 79 million with medical bills or debt, some of the highest prescription drug costs in the world and a proliferation of crowdfunding sites hoping to cover medical expenses.

Of the myriad concerns animating Democratic voters, health care has consistently topped polls of the most important issue. It was a driver for the party’s 2018 midterm success when it won back the House of Representatives, and it has carried over into the 2020 primary as a record-setting field of candidates vie for votes. But with confusing terminology, blurry lines and some candidates supporting more than one plan, it can be difficult to tell what exactly is what regarding health care policy.

Government-subsidized health care (apart from that provided to military veterans) began in the 1960s with Medicare for Americans older than 65, and the pushback from Republicans began immediately; Ronald Reagan made his political reputation by recording a speech for the American Medical Association titled “Ronald Reagan Speaks Out Against Socialized Medicine.” (Republicans still quote from his warning that someday Americans would look back with nostalgia on a time “when men were free” — usually without mentioning the context.) Both before and after Medicare, Democratic proposals for government-funded health care have been stymied, including Harry Truman’s efforts in the 1940s and the failure of a universal plan in President Bill Clinton’s first term.

After a titanic struggle in Congress, President Obama managed to get the Affordable Care Act passed into law in 2010. Republicans painted Obamacare as a socialist takeover despite the fact it was based on a plan from the conservative Heritage Foundation that was first implemented by Republican Gov. Mitt Romney in Massachusetts. The Trump administration and Republican Congress’s attempt to repeal Obamacare in 2017 resulted in testy town halls and rising support for the oft-criticized program, but 2020 Democrats have come out in support of a number of plans to not just stabilize the system but push it much further.

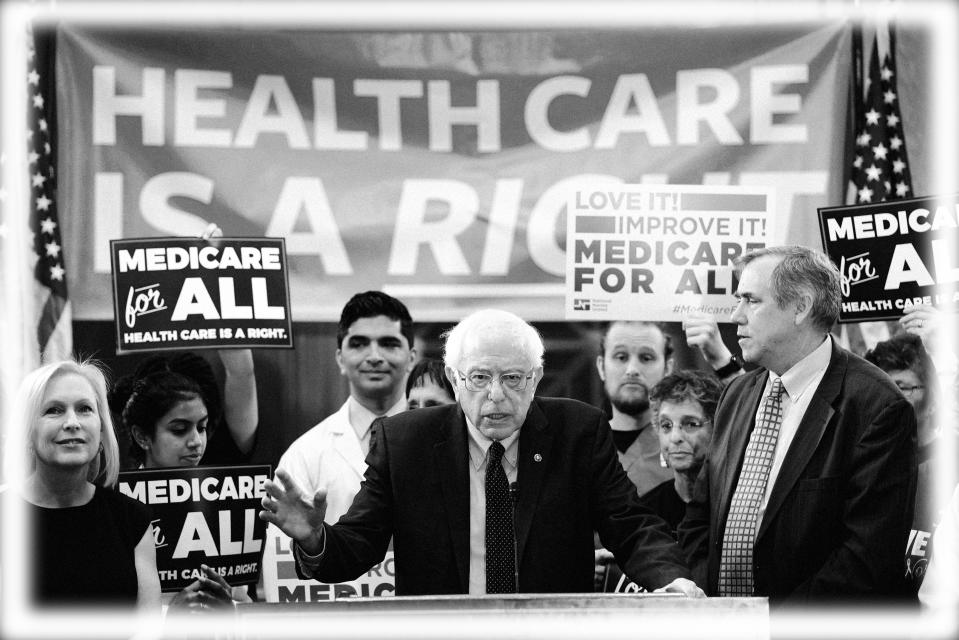

Virtually all the Democratic candidates have plans to expand health care coverage, of which the best known is Medicare for All, which Sen. Bernie Sanders ran on in the 2016 primary. He released an updated version of the legislation in April, with fellow presidential candidates Sens. Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Cory Booker and Kirsten Gillibrand as co-sponsors.

While the proposal is referred to as Medicare for All, it would eventually end Medicare as it exists, along with Medicaid and private insurance, replacing it with a more robust health care plan that would cover all patient bills without the need for supplemental insurance. The plan would cover routine doctor visits, surgery, mental health, prescription drugs, dental and vision for everyone in America, attempting to achieve universal coverage. The Sanders plan would also cover women’s health services such as abortion, which would be controversial and require the elimination of the Hyde Amendment, which prevents federal money from going toward abortion.

After years of pushing from activists, the 2019 edition of Sanders’s plan expands long-term care, helping individuals with disabilities who are not fully covered by Medicare as it exists. The long-term care provision was also present in corresponding House legislation put forth by Rep. Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash., and received praise from Ady Barkan, an activist for both Medicare for All and disability rights.

“It is incredibly harmful that disabled people need to impoverish themselves and family in order to qualify for Medicaid and home- or community-based care,” Barkan told Yahoo News. “So many people are currently forced to choose between leaving their home for a facility, living in poverty and going without needed care. In the richest country in the history of the world, we must do better. If we are going to have a single-payer system, then it obviously needs to cover the most vulnerable people, and the ones who use health care the most. We were very glad to see Rep. Jayapal and then Sen. Sanders take our concerns so seriously and adopt the smart and just policy stance.”

Sanders’s Medicare for All proposal is a single-payer plan, with that lone funder in this instance being the government, which would pay for everyone’s health care. The Sanders plan does not go as far as some countries, such as the United Kingdom, where medical personnel work directly for the government via the National Health Service. That is the model followed by the Veterans Health Administration in the United States, through which veterans receive care from hospitals run directly by the government employing doctors and nurses and negotiating directly with drug companies.

Other candidates — including some of the Sanders co-sponsors and former Vice President Joe Biden — support a public option. There are various versions of that plan, but the basic idea is to allow some or all Americans the option to buy into a public Medicare or Medicaid-style plan if not the programs themselves. Supporters of the public option say it would allow those who like their private insurance plans to keep them and reduce the disruption to the economy.

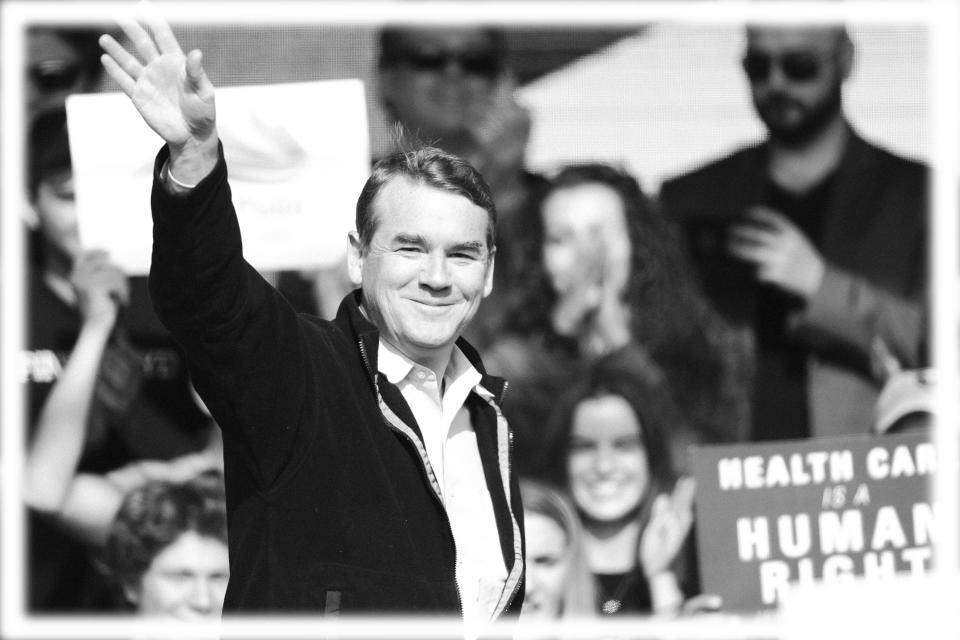

One of those plans is the Medicare-X Choice Act, introduced by Sen. Michael Bennet, one of the Democratic primary candidates, and counting Harris, Booker and Sen. Amy Klobuchar among its co-sponsors. Under the Bennet plan, individuals who work for small businesses or who get their plan from the exchange could buy into a plan that would allow access to the Medicare network at set Medicare costs for their employees. (Those who receive their insurance through larger employers would not be permitted to switch over, limiting the eligible pool.) It would initially limit who could buy into the plan — those in Obamacare markets with one insurer or high costs — for the first few years while expanding tax credits to help people purchase insurance. Medicare X would cover the 10 essential health benefits laid out by Obamacare (including emergency services, hospitalization, pregnancy and newborn care, prescription drugs and mental health services) but not dental or vision. There is also some confusion about terminology: Some Democratic voters who say they support Medicare for All describe a public option as opposed to an end of private insurance as prescribed in the Sanders bill.

“180 million people in America get their insurance through an employer-based plan and Medicare X gives people the opportunity to decide whether they want to stay on that plan,” said Bennet in a March interview with Politico. “Some of the other plans take away insurance from those 180 million.”

“When you think about the Medicare for All proposals, they envision a very different way of providing and paying for health care services than a public option,” said Jennifer Tolbert, director of state health reform for the Kaiser Family Foundation. “They get much closer to achieving universal coverage and provide a much broader set of benefits to enrollees and really limit cost-sharing. In many ways what you’re seeing is a broadening of coverage for consumers, a limiting of consumer out-of-pocket costs and instead shifting those costs to the federal government.”

As far as the incumbent, Trump has promised a great health care plan that lowers costs and covers everyone, a vague proposal devoid of any specifics that echoes his 2016 campaign position of what he would do after scrapping his predecessor’s signature program.

Supporters of a single-payer plan like Medicare for All say that a public option is simply another incremental step, like Obamacare, that perpetuates the power and profits of the private insurance industry while failing to achieve universal coverage. Public option critics also point to the fact that even if the intent of the plan is to allow Americans to retain their private insurance, millions have coverage disrupted or lose preferred doctors every year due to job loss, employers changing offered plans or physicians moving out of network.

Those against Medicare for All say it would be too hard to implement, result in underfunded hospitals due to lower Medicare-rate payments and not provide enough options for consumers.

“Right now, we subsidize private companies with hundreds of billions of dollars so they can offer you complicated insurance plans you can’t afford to purchase and can’t afford to use,” said Tim Faust, a Medicare for All activist who is against the public option. “Every other political health care bill out there involves keeping, or deepening, this relationship. It’s a waste of your public money, a waste of your time and a waste of tens of thousands of lives a year. Only a single-payer plan like Medicare for All takes our health care spending and uses it to address both the problems of health care costs and health care coverage, giving you significantly cheaper health care and the choice of virtually any doctor in America.”

As for paying for the plans, Sanders’s office released a number of potential options, many focused on raising taxes on the wealthy. Because his plan would eventually eliminate jobs with private insurers, the Medicare for All legislation also includes assistance in helping those employees find new jobs. One estimate pegged the Sanders plan as costing $32 trillion over a decade, but that price tag comes in below projected costs should the current system remain unchanged. Bennet’s Medicare X public option plan would attempt to pay for itself via premiums, with no other provisions for financing sources save for $1 billion in startup costs.

Any attempt to overhaul the health care system and eliminate most if not all private insurance is going to be met with great resistance from the powerful industry in which CEO pay topped $1 billion last year. A group of drugmakers, insurance companies and private hospitals spent $143 million lobbying last year alone, a number sure to go up if a Democratic president were to make a push for increased government health care.

On the polling front, Americans have been generally supportive, but responses vary depending on the survey and the type of information is given. For example, an April poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 63 percent of respondents had a positive response to the terms “universal health coverage” and “Medicare for All” but just 49 percent felt the same way about “single-payer health insurance system.”

Read more from Yahoo News: