A fight over college textbook prices is leaving students unsure who to believe about costs

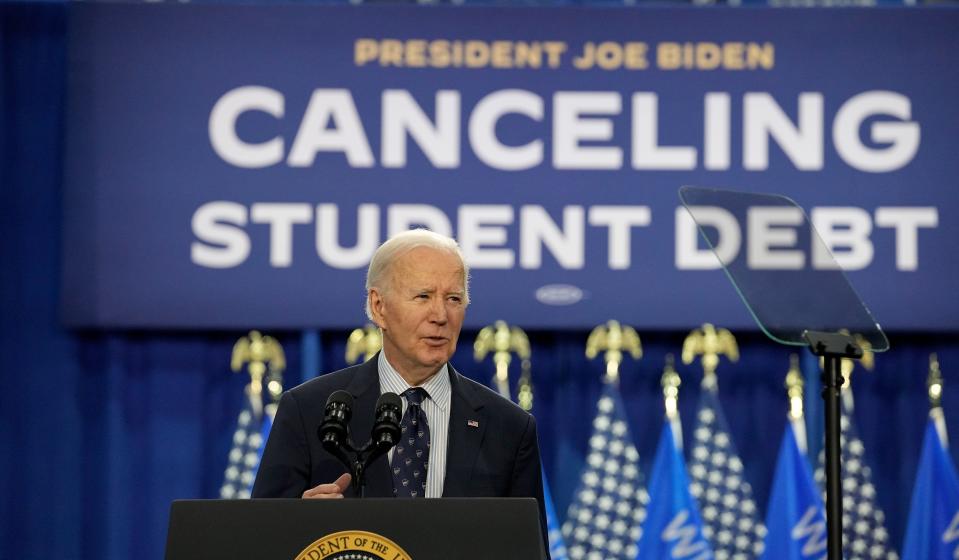

President Joe Biden's crusade against so-called "junk fees" is on its way to college campuses, and some of the pushback is fierce.

Some university leaders say a planned change to an Obama-era regulation could raise prices on textbooks and other course materials for students nationwide. Publishers are in a panic, accusing the Biden administration of upending a pricing model they’ve spent years perfecting to offer affordable digital materials to millions of students on the first day of class.

Backed by consumer advocates, Education Department officials see it differently. They argue the model currently favored by colleges and textbook companies is akin to automatic billing and leaves out vulnerable students. The Biden administration says it’s just trying to give college students more say in the ever-mounting fees listed on their bills.

Some students and professors are worried the effort will backfire. Others are happy to have more control over their college costs. It’s unclear exactly how the change, which could take effect next year, will affect students’ bank accounts. But the implications will likely depend on how publishers react, the types of colleges students attend and their own individual financial situations.

The disagreement has played out in recent months in a sometimes-contentious federal rulemaking process. It highlights a key part of Biden’s strategy to curb college costs: the president has told his advisors that making higher education more affordable must be an accessory to the billions of dollars in student loan forgiveness he’s approved. As with their debt cancellation efforts, federal officials are pushing the change through on their own, avoiding Congress altogether.

"The Biden-Harris Administration will continue its efforts to make higher education more affordable and accessible, as well as to eliminate hidden, surprise, and junk fees and put cash back in the pockets of Americans," the White House said in a March statement.

Unlike other components of Biden’s campaign to reduce the financial burden of higher education, the debate over how to fairly set costs for college course materials, including textbooks, has a long history. Examples of schools abusing their pricing power is part of the rationale the administration is using.

Read more: Colleges charge tons of junk fees for food and books. Biden may force them to scale back.

Yet as federal officials mull over a final version of the rule, a messaging war has broken out between colleges, publishers and the government. It's leaving some students without a clear sense of whether prices will rise or fall in the coming years.

“It’s easy in these conversations to assume that what is good for some students is good for all students,” said Nicole Allen, a college affordability advocate who supports the administration’s proposal. “Students are not a monolith.”

What is inclusive access?

In the decade between 2006 and 2016, college textbook prices ballooned by 88%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Hoping to repress the trend, the Obama administration approved a regulation allowing colleges and universities to charge students for course materials as part of their tuition and fees. Some affordability advocates scoffed at the change, later arguing the Education Department “effectively eliminated competing textbook markets.” Supporters have said the rule ultimately helped bring costs down.

The regulation had a few caveats. Schools needed to work with publishers to offer materials at “below competitive market rates," a threshold critics say was not well defined. And colleges had to give students the choice to opt out of the program.

Over the next few years, the controversial (but widely used) term “inclusive access” took hold as the pricing model became more widespread. Many colleges worked with textbook publishers to create digital textbooks that students could access on the first day of class. Schools then tacked the bills for those course materials onto students’ overall fees.

Bill Hoover, a science professor at Bunker Hill Community College in Massachusetts, said it was a game-changer. The textbook companies his school works with developed interactive platforms his students could use to quiz themselves. They performed virtual cadaver dissections. Some of them opted out of the program. But when they did, they usually regretted it, he said.

He’s anxious those resources could become far more costly.

“It’s the only way to guarantee that everybody completes the course on equal footing,” said Aspassia Akylas, a 28-year-old nursing major at Bunker Hill. “I don’t really see why any other alternatives would be beneficial.”

A euphemism for ‘automatic billing,’ critics say

Proponents of the Biden administration’s efforts said inclusive access is more accurately described as a euphemism for “automatic billing,” which is typically a red flag to consumer protection advocates.

“If a business is engaged in automatic billing for a product or service, that usually is a tip that the product or service is not all that it’s cracked up to be,” said Carolyn Fast, the director of higher education policy at The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank.

Opponents, meanwhile, accused the Education Department of tuning out the people who could be most affected by the new rule.

“The Department of Education just seems to be ignoring critical testimony from faculty, students and administrators,” said Kelly Denson, senior vice president at the Association of American Publishers, which represents the major textbook companies.

Yet students seem divided on the proposal, with many pushing hard for it to become the new normal.

Joel Sadofsky, a junior at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota, spoke before a government panel earlier this year, applauding the Education Department for giving students more choice. In an op-ed for his school newspaper published in February, he argued an inclusive access program touted by administrators had the potential to hurt students' wallets.

“The Department of Education needs to work hard to reign in the power of these textbook vendors,” he told USA TODAY.

The federal government is expected to finalize the rule by November, although any changes likely wouldn't take effect until next summer.

Zachary Schermele covers education and breaking news for USA TODAY. You can reach him by email at [email protected]. Follow him on X at @ZachSchermele.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Biden wants to curb textbook fees. Publishers warn it may backfire.