Gerald Ensley: If not for FAMU, we would all be poorer

(This column was first published in the Tallahassee Democrat on Nov. 18, 2012)

If there had been no University of Chicago or University of California-Berkeley, maybe the nation would have fewer Nobel Prizes. If there had been no University of Pennsylvania or M.I.T., maybe the nation would have fewer titans of business.

But if there had been no Florida A&M University, the city of Tallahassee, the state of Florida and the nation would have been a poorer place in many ways. Because over the course of its 125 years, FAMU has been one of the nation's leading producers of opportunity for Black citizens — which has benefited us all.

FAMU was a place Black students could get a college education in the days before integration. It has been a university where Blacks learned the professional skills that created a more diverse workforce. It's been a university that helped everyone to share in the American dream.

"In a very significant way, the existence of FAMU provided the opportunity to say, 'How wonderful could we be when everybody has the ability to compete and live equally,' " said Frederick Humphries, the FAMU president from 1985 to 2001. "Without a FAMU, the wherewithal in terms of human resources to make a more productive, more diverse society would not have been possible."

FAMU, one of the nation's 105 historically black colleges or universities (HBCU), is celebrating its 125th anniversary. It opened its doors on Oct. 3, 1887, as the State Normal College for Colored Students. In 1909, it became Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College and since 1953 has been Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University.

FAMU has been the leading producer of Black college graduates in Florida, often accepting students who would not have been accepted at other universities because they come from personal or academic backgrounds of reduced circumstances. Some argue such students shouldn't be admitted to universities. But not Bill Tucker, a retired FAMU physics professor and longtime president of its faculty union.

"I heard someone say once that if HBCUs didn't exist, we'd have to invent them: If not for FAMU, a lot of these kids would never get a higher education," Tucker said. "I've heard the argument we don't need all kids going to college. But Black families have found that's the road to success. It's harder for Black kids to drop out like Bill Gates and start Microsoft, because they don't have a lot to fall back on."

Leading the charge for civil rights

Ensuring that kind of opportunity was one of the tenets of the civil rights movement in the 1960s — where FAMU made one of its greatest contributions because FAMU students were at the forefront of the local civil rights movement.

In 1956, after two FAMU students refused to go to the back of a city bus, FAMU students sparked the Tallahassee bus boycott. In 1960, it was FAMU students who staged sit-ins at Tallahassee lunch counters and participated in the famous jail-in, in which eight students arrested chose to spend 49 days in jail rather than pay fines, an act that gained national attention.

Two of those jailed were sisters Patricia and Priscilla Stephens, who became leaders of the FAMU student protests. In 1963, Patricia Stephens (Due) led FAMU students in demonstrations at segregated Tallahassee movie theaters, with one protest resulting in more than 500 students being jailed in the cattle barns of the county fairgrounds.

That summer, after her sister was jailed for protesting civil rights arrests in Ocala, Priscilla Stephens (Kruize) initiated the first of four years of demonstrations by FAMU students against the segregation of Tallahassee municipal pools.

"The activity of student protesters at FAMU is unprecedented; students at no other school did as much or produced as much (change) as did FAMU students," said retired FAMU professor Charles U. Smith, author of two books about civil rights protests. "It changed Tallahassee, as even those opposed (to civil rights) realized they had to deal with it. There's not a chance civil rights would be as far along (without FAMU)."

Growing professional programs

FAMU offers bachelor's degrees in 62 subjects, master's degrees in 39 subjects and has 11 doctoral programs (counting its law school in Orlando). FAMU has produced significant research in fields such as biology, chemistry, pharmacy and physics — where students recently helped develop the Spheromak, a device to aid research into fusion energy. FAMU professors and researchers have authored hundreds of papers for major academic journals.

Tucker said one of FAMU's greatest contributions is its professional programs that have allowed it to carve out a niche among state universities and train graduates for professions where minority representation has been traditionally low. Such programs include FAMU's schools of architecture, pharmacy, allied sciences and journalism.

FAMU's School of Business and Industry was founded in 1974 by longtime dean Sybil Mobley, who retired in 2003. Though the school is unaccredited, Mobley's zeal made SBI the leading producer of Black business graduates in the nation for many years (it still ranks in the top five) and Mobley's contacts made SBI the go-to hiring stop for major corporations.

The school produces 150 to 200 graduates per year. Eighty-five percent of those who earn an MBA (masters in business administration) are hired immediately; the remainder go on to pursue a Ph.D. or law school. Sixty-five percent of those who earn a bachelor's degree also are hired upon graduation, with most of the remainder going on to graduate school.

"We have definitely demonstrated young African American students can leave here and hit the ground running as professionals, which is a testament to the impact Sybil Mobley had on the lives of people and their careers," said Shawnta Friday-Stroud, an SBI grad who joined the faculty in 1997 and became dean in 2009. "(Students) are going to come out of here with the kinds of job offers and salaries they wouldn't get if not for FAMU."

Opening doors for minority journalists

In 1974, when FAMU's School of Journalism & Graphic Communication was created, minorities accounted for less than 4% of the nation's newspaper and TV reporters. Today, more than 12% of the nation's journalists are minorities.

Though several HBCUs have journalism schools, FAMU's was the first to be nationally accredited (1982). That spurred other HBCUs to improve their programs and seek accreditation, helped FAMU place 110 students per summer in internships at major media outlets and increased the numbers of minorities hired to full-time journalism positions.

"I think we at FAMU got the ball rolling (in minority journalism education) and pretty quickly turned out some quality people," said Bob Ruggles, retired founding dean (1974-2003) of FAMU's J-School. "There's no question (minorities) have helped journalism.

Generally speaking, there were not enough Black reporters who could go into the minority communities, find out what the problems were and bring them to light. I think (minority reporters) helped people understand it's not just a white world out there anymore and you have to pay attention to everyone."

Training Black Army officers

A similar, if often overlooked contribution of FAMU has been its Army ROTC program. Started in 1948, when President Harry Truman ordered the desegregation of the U.S. military, the FAMU ROTC program has produced 1,390 commissioned officers. That number includes former president Humphries, as well as three Army generals and hundreds of full colonels.

Today, many Black men and women attend the nation's military academies and ROTC programs in all major universities. But HBCUs still contribute the majority of Black officers; for more than 40 years, FAMU was the single biggest contributor of Black Army officers.

"FAMU has been able to put outstanding officers of color into our armed forces and help our armed forces accept the color of your skin is not a factor in your ability to perform," said retired Col. Ronald Joe, a 1966 FAMU ROTC graduate who twice taught in the school's ROTC program. "It's helped us have a stronger military and finish what Truman started."

Contributions to sports, music, history

Without FAMU, the worlds of sports and music would have been poorer.

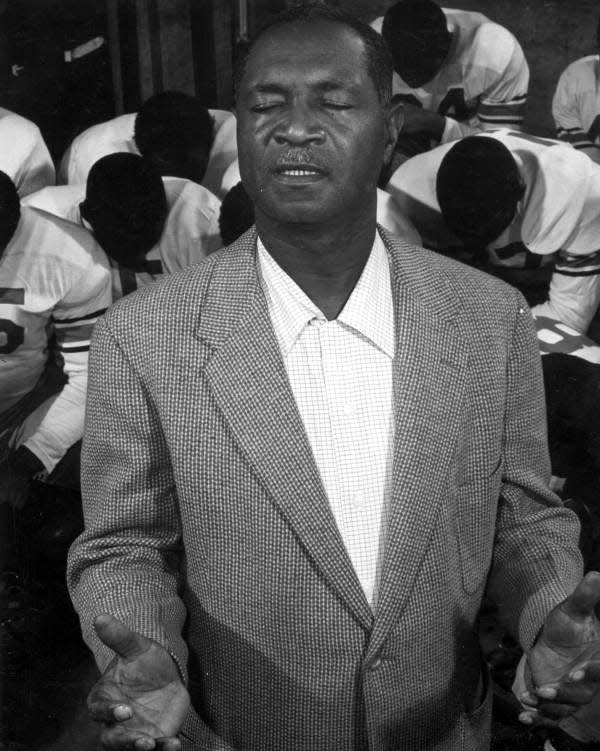

In the 1930s and 1940s, white fans flocked to FAMU football games, as the legendary Jake Gaither-coached Rattlers provided Tallahassee residents their only college football games before Florida State University began its program in 1947.

In the 1950s, FAMU football players Willie McClung (Pittsburgh Steelers) and Willie Lee (Chicago Bears) were among the first Blacks in the NFL. In 1957, FAMU grad Althea Gibson became the first Black woman to win the Wimbledon women's tennis title, the second of her five Grand Slam titles.

In 1964, FAMU's Bob Hayes won gold medals in the 100-meter dash and 400-meter relay and became known as the "World's Fastest Human." Hayes then revolutionized pro football with his speed as a receiver for the Dallas Cowboys, becoming the only athlete in history to win an Olympic gold medal and a Super Bowl.

Though now suffering from last year's hazing scandal, FAMU's Marching 100 band is easily the world's most recognizable marching band. Created by the late band director William P. Foster, the Marching 100 has played innumerable Super Bowls, television commercials and bowl parades, as well as being the only American band to participate in France's Bicentennial celebration in 1989.

Perhaps one of FAMU's most important ongoing contributions is its preservation of history.

In 1975, the late James Eaton founded the FAMU Black Archives and began collecting the artifacts of Black history from all over the nation.

The collection now occupies two buildings on campus and one downtown. The archives have more than 500,000 artifacts, newspapers, books and photos. More than 100,000 people every year visit the archives — where admission is free — or participate in its many events.

"If not for the archives, if not for FAMU, we might not have this part of the story, this piece of the American pie," curator Murell Dawson said. "I think part of our contribution is not necessarily educating African Americans about our history but offering a view of our life to people of other ethnicities. Not to sway their attitudes, but for them to walk through and say, 'My Irish grandmother had an iron like that.' To realize we're all humans. We're all here today. How can we make this place better and learn from our history.

"I hope that's what FAMU has done."

Gerald Ensley was a reporter and columnist for the Tallahassee Democrat from 1980 until his retirement in 2015. He died in 2018 following a stroke. The Tallahassee Democrat is publishing columns capturing Tallahassee’s history from Ensley’s vast archives each Sunday through 2024 in the Opinion section as part of theTLH 200: Gerald Ensley Memorial Bicentennial Project.

JOIN THE CONVERSATION

Send letters to the editor (up to 200 words) or Your Turn columns (about 500 words) to [email protected]. Please include your address for verification purposes only, and if you send a Your Turn, also include a photo and 1-2 line bio of yourself. You can also submit anonymous Zing!s at Tallahassee.com/Zing. Submissions are published on a space-available basis. All submissions may be edited for content, clarity and length, and may also be published by any part of the USA TODAY NETWORK.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: Gerald Ensley: If not for FAMU, we would all be poorer