'Good Day Sunshine State' tells of Beatles' impact on Jacksonville and Florida in 1964

When the Beatles came to Jacksonville in September 1964, a Florida Times-Union writer, on assignment in the Gator Bowl in the midst of more than 20,000 screaming teenagers, gave this assessment of the British band: "Three of them play guitars. Ringo pounds the drums and they all sing after a fashion."

Meanwhile, an editorial in the paper wrote off the "mop-topped 'artists'" — notice the quote marks around 'artists' — as just a "passing fad," one that fits the "mores, morals and ideals of a fast-paced, troubled and frenetic era."

Those blithe dismissals were a common reaction to the Beatles back then. Today, of course, they seem comical, given the musical significance the band still holds.

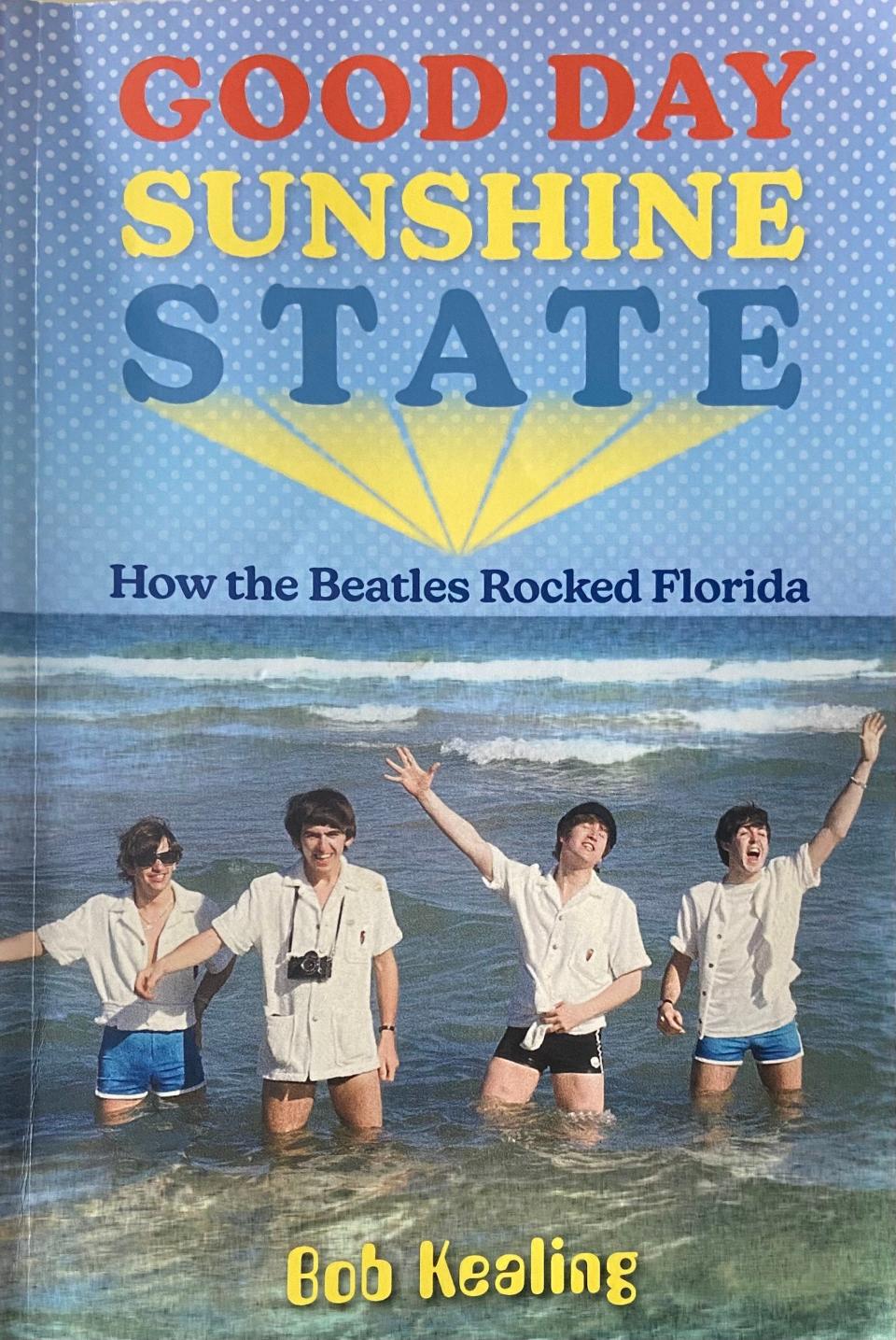

But Bob Kealing, author of a new book called "Good Day Sunshine State," argues that even as early as their first USA tour in 1964, the band was also quite consciously making cultural and political statements that would reverberate across the world, their mop-tops and irreverent antics aside.

Beatles commentary: Why the Paul McCartney shoutout in Jacksonville’s RNC video raised some eyebrows

George Washington Hotel: The GW welcomed the Beatles, Judy Garland, Veronica Lake and more

Those who underestimated them, he believes, did so at their peril.

"Good Day Sunshine State," published this month by the University Press of Florida, focuses on the Beatles' trips to Florida in 1964, to Key West and Miami and to stormy Jacksonville, where they landed just after Hurricane Dora.

Kealing sets the story against the backdrop of the struggles for racial equality in St. Augustine and elsewhere, which culminated in the signing of the Civil Rights Act that July.

He tells how the Beatles, who traveled with a Black opening act, the Exciters, had a stipulation in their performance contracts that they wouldn't appear if audiences were segregated by race.

And he quotes John Lennon, who declared on that tour: "We never play to segregated audiences and we're not going to start now."

That was one of numerous clear statements on that issue that the band made in 1964, all of which went out to nationwide audiences eager for any scrap of news about the Beatles.

“They were very much proactive change agents," Kealing said. "If you look at the rider in their contracts, this was going back to the spring of 1964 before the Civil Rights Act was signed. They said it’s a moral stand, a line in the sand, and we’re not going to cross it.”

The Beatles and Florida

Kealing, 58, is a retired broadcast journalist who spent 25 years on the air in Orlando. He's also the author of two other books that focus on Florida and music: "Calling Me Home: Gram Parsons and the Roots of Country Rock" and "Elvis Ignited: The Rise of an Icon in Florida."

For his book on the Beatles, he jokes that he came up first with the title for "Good Day Sunshine State," a play on their song "Good Day Sunshine," then decided he'd better write a book to go with that title.

All kidding aside, he recognized that there was plenty of material for a book on Florida's connections to the Beatles, who spent more time in the state in 1964 than in any other location. “I knew it was not only a story, there was some real meat to it,” Kealing said.

He conducted interviews with at least 30 people who were there, including a journalist who toured with the band, a policeman who provided security and friendship and fans who attended shows. Kealing shows how the Beatles, all in their early 20s, marveled at the palm trees and tropical vibe of South Florida, as seen in the cover, a classic Associated Press photo of the band frolicking in the ocean off Miami Beach (George Harrison, like a good tourist, has a camera around his neck).

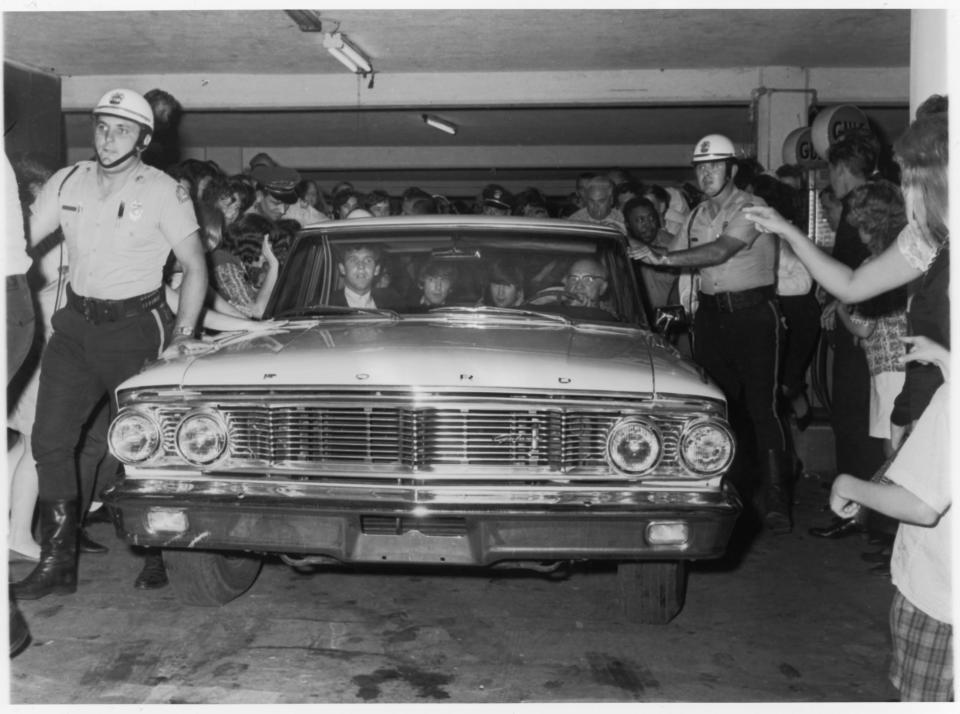

And he shows how the band, after coming back to Florida to play in Jacksonville, took refuge in Key West following a grueling tour that included a scary death threat against Ringo Starr.

Jacksonville, LBJ, MLK, a hurricane and the Beatles

A big chunk of the book focuses on Jacksonville and the band's Sept. 11, 1964, performance at the Gator Bowl, where Starr insisted that his drum kit be fastened to the stage so it wouldn't fly away in the gusty winds left over from Dora.

Kealing intertwines that appearance with the then-recent civil rights protests in St. Augustine, which attracted national attention and violent counter-protesters. Attention grew when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, brought what he called his "nonviolent army" to the city to fight segregation and rally national support for passage of the Civil Rights Act.

In 1964: Martin Luther King Jr.'s stop in St. Augustine hastened passage of Civil Rights Act

Civil rights movement in Jacksonville: Beatles force desegregation of their concert in Florida

Super Bowl XXXIX: Paul McCartney and more for Jacksonville Super Bowl in 2005

The book also focuses on Bryan Simpson, a white federal judge in Jacksonville who made a series of bold civil rights decisions in the 1960s, including overturning St. Augustine's ban on nighttime civil rights marches. That decision came after hearing testimony from King in Jacksonville, where he'd been held in solitary confinement after an arrest in St. Augustine.

"The times were definitely a-changing in Jacksonville, and the African American story and experience is so intertwined with the Beatles and their visit, you can’t tell their story without telling that," Kealing said. "And Jacksonville and St. Augustine are just a huge part of that.”

Kealing believes there should be a historical marker on Julia Street in downtown Jacksonville, where the U.S. courthouse once stood and where King testified. It's also the site of the old George Washington Hotel, which reportedly refused to segregate its accommodations; instead of staying there, the Beatles flew out following the Gator Bowl show, Kealing writes.

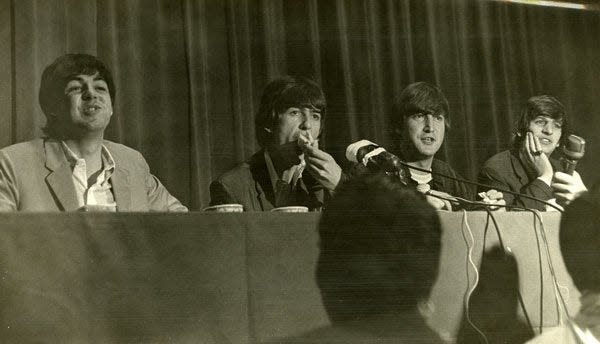

The band did, however, hold a pre-concert news conference at the George Washington where they made typically light-hearted jokes. But after being asked if he knew that President Lyndon Johnson had been in town (he'd come to survey hurricane damage), Starr joked: "Well I hope he had better luck getting a room than we did."

Lennon also alluded to the situation, saying: "We don't do the booking or the canceling. Must be some reason why we're going on. We're trying to catch the hurricane."

At the Beatles' insistence, the Jacksonville concert, like all their others that year, was integrated. It went smoothly, hurricane and all.

In "Good Day Sunshine State," Kealing quotes young journalist Larry Kane, who traveled across America with Beatles. "The Gator Bowl concert, which people had long assumed would become a simmering controversy over racial injustice, ended quietly by Beatles standards," Kane wrote. "Blacks and white sat side-by-side, sharing an experience. The Beatles had prevailed."

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: New book chronicles the Beatles in Jacksonville and Florida