History: James Baldwin’s civil rights and poetry in Palm Springs

In three spare and widely spaced type-written pages, the Black, gay, expatriate, erudite man of letters recorded a birthday message for his sister in a poem entitled Some Days. James Baldwin, by then, was living in the south of France, no longer able to tolerate the hypocrisy and violence of racism in his own country.

The poem was set to music by pianist Steven Marzullo and made an anthem for the LGBTQ community by soprano Audra McDonald. She performed the song for DAP’s Steve Chase Humanitarian Awards in Palm Springs in 2011. Pull up one the many YouTube videos of it and prepare to cry at the sheer humanity of the poem, the music and her performance.

Famous as a novelist, civil rights activist and poet, Baldwin according to Ed Pavli? writing in the Boston Review in 2018, conceived of himself as a bridge between the Freedom Movement of the 1950s and the more radicalized Black Power of the late 1960s.

It seems unlikely that Baldwin himself would have ever been in the desert, but astonishingly he was indeed here in 1968, and in some interesting company. Pavli? captured a poignant moment of Baldwin’s visit that even Hollywood wouldn’t have dreamt up for a movie.

According to Pavli?, two weeks into his stay in Los Angeles in February 1968, Baldwin wrote his brother about the strange scene of Black radicals coming to see him at the Beverly Hills Hotel where Columbia Pictures had initially put him up after hiring him for a screen adaptation of the life of Malcolm X. The Beverly Hills Hotel proving uncomfortably surreal, Baldwin decamped to Palm Springs.

“On the afternoon of April 4, 1968, James Baldwin was relaxing by the pool with actor Billy Dee Williams in a rented house in Palm Springs. Columbia Pictures had put Baldwin up there after commissioning him to write a film adaptation of Alex Haley’s The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965); Williams was Baldwin’s pick to play Malcolm. The men were listening to Aretha Franklin when the phone rang. Upon hearing the news that Martin Luther King, Jr., had been assassinated, Baldwin collapsed in Williams’s arms.”

“King’s murder made Baldwin feel like the last person capable of bridging the divide between his generation and younger activists. In a way he considered very un-American, Baldwin understood that generations depend upon each other.” His poem, Some Days, alludes to understanding that, and the comfort that gives. Generations depend upon each other.

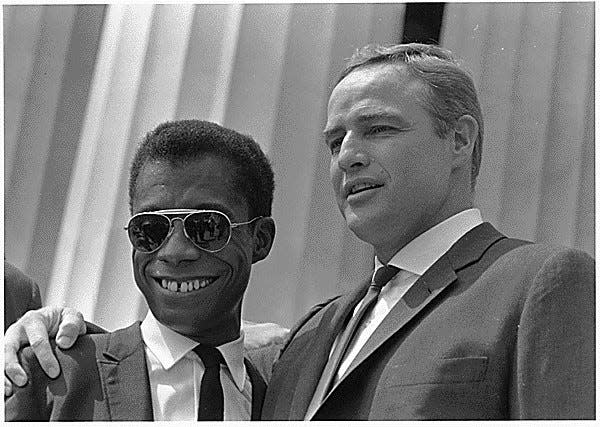

In the two weeks prior to King’s assassination, Baldwin had spoken at Carnegie Hall in honor of W. E. B. DuBois and alongside King; and with Marlon Brando, had introduced King at a fundraiser at Anaheim’s Disneyland Hotel.

Pavli? writes, that “in Baldwin’s estimation, King was struggling to guide what remained of the Freedom Movement, contending with the growing appeal of younger militants … while traveling nonstop to support nonviolent action wherever it showed promise. The Freedom Movement had always been chaotic. But by 1968 it was a volatile tumble of organizations, personalities, and philosophies. All were entangled in an increasingly violent culture … As an artist and as an activist himself, Baldwin was astraddle languages of black assertion that were splintering between generations”.

“Introducing King in Anaheim, Baldwin tried to remind listeners that King and younger activists were working toward compatible goals. Radicals hadn’t appeared out of nowhere. Baldwin described the journey from 1955 to 1969 as a ‘terrible descent.’”

Just two months later with the death of King and, “citing grief, exhaustion, and the perilous political weather of the era, Baldwin wrote that, with so many of his cohort murdered, including Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and now King, he felt overcome by both a despairing silence and an ethical burden to speak. King’s murder made Baldwin feel singled out, dangerously exposed, perhaps the last black public intellectual alive capable of bridging the ideological divides separating the leaders of his generation from those who had emerged since ….”

Journalist C. Robert Jennings made the trip to Palm Springs to interview Baldwin for the Los Angeles Times, noting “he is slight, black, jagged, young but his pain is patently old and central – wounded eyes, scarred nose and deep facial creases are witness to it – and one remembers a character in one of his books with ‘pain so old and deep and black that it becomes personal and particular only when he smiles.’ He smiles easily; but just now, in an unextraordinary house on the lower slopes of Palm Springs’ San Jacinto Mountain, he sips coffee….”

Staying nearby at the home of Winthrop Rockefeller, and hanging out with Baldwin, was Whitney Young, Jr., the executive director of the National Urban League and syndicated columnist is 100 newspapers across the country and “one of the three or four top-echelon Negro leaders in the nation, one of the two with a direct pipeline to the White House (the other: Roy Wilkins) and perhaps the only one welcome in any boardroom in America.”

Rockefeller was the former governor of Arkansas and the grandson of the oil magnate. He’d made a political career for himself in Arkansas according to the New York Times “having softened, at least officially, its racial prejudices. As Governor he replaced Orval E. Faubus, one of the South's most vocal segregationists.” When Faubus stationed the National Guard at Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957 to prevent nine black students from integrating classes, Rockefeller publicly objected.

As he spent limited time in Palm Springs, Rockefeller lent his home to Young that year. With Baldwin in the neighborhood working for Hollywood and his friend Truman Capote across the way, the discussions must have been lively.

Jennings described the scene at the Rockefeller house on the escarpment of San Jacinto, “After many cucumber sandwiches and much seafood salad, a steady procession of beers and whiskies, Jimmy Baldwin prongs his fingers histrionically for a steely goodbye to Whitney Young… He is at once tense, graceful, epicene, dramatic….” And always poetic.

Jennings continued, “Later in his own living room, Braques and Picassos mutely watching, Baldwin scribbles some script notes in a finishing-school longhand. ‘And the mother’s fears increase, and the conflict between her and her husband, and the differences between them, grow. We focus on Malcolm, watching and listening, and now he has begun to feel sorry for his father.’ He underlines the last ten words in red pencil. He wants Ossie Davis and his wife, Ruby Dee, to play Malcolm’s parents. Dinah Washington sings Drinking Again and, like all the singers he cares about – Aretha Franklin, Mahalia Jackson, Bessie Smith – he likes her loud to drown the lonesomeness.”

“He stops writing: ‘I got to bust out of here. Palm Springs is Death Valley. Eartha Kitt has offered me one of her houses in Beverly Hills. (But subsequently, he moved into the home of a princess in Benedict Canyon.) This is Another Country. Only this country is a strange place to me. It’s a millionaire’s graveyard. I’m not a millionaire, and I’m not about to die. All I’m doing is working, hard….”

By the end of 1968, Baldwin had decided that he couldn’t work with the movie industry. He finished his script and published it as One Day, When I Was Lost in 1972. Pavli? writes, “But by then Columbia Pictures had moved on, and so had Baldwin. Of the experience, he would later write in The Devil Finds Work (1976), ‘I would rather be horsewhipped, or incarcerated in the forthright bedlam of Bellevue, than repeat the adventure.’”

Baldwin told Jennings that in a curious way, Malcolm himself had given Baldwin the movie assignment. “The last time I saw him … his youngest child was lying across (his wife) Betty’s lap, and I asked Malcolm the question which comes in The Grand Inquisitor part of Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov: ‘If you knew you could save mankind by dashing this baby against the rocks, would you kill this baby?’ He just looked at me and said: ‘I’m the warrior of this revolution, Jimmy, and you’re the poet.’”

Tracy Conrad is president of the Palm Springs Historical Society. The Thanks for the Memories column appears Sundays in The Desert Sun. Write to her at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: James Baldwin’s civil rights and poetry in Palm Springs