In rural Colorado, the only hospital for miles worries about its future under ACA repeal

DELTA, Colo. — Delta County Memorial Hospital has been around for as long as Ed Sisson can remember. When he was a kid, it was a small, single-story building a few streets off the main downtown strip, with a handful of doctors and a couple of dozen beds, a godsend for patients unable to make the drive of roughly an hour from here to Grand Junction, the largest nearby city.

Now, it’s in a building twice as large, sitting atop a hill on the east side of town overlooking a sweeping valley on Colorado’s Western Slope. Many decades later, it continues to be a lifeline for this vast rural area, where doctors and medical facilities are still few and far between for a population that is increasingly older and less affluent.

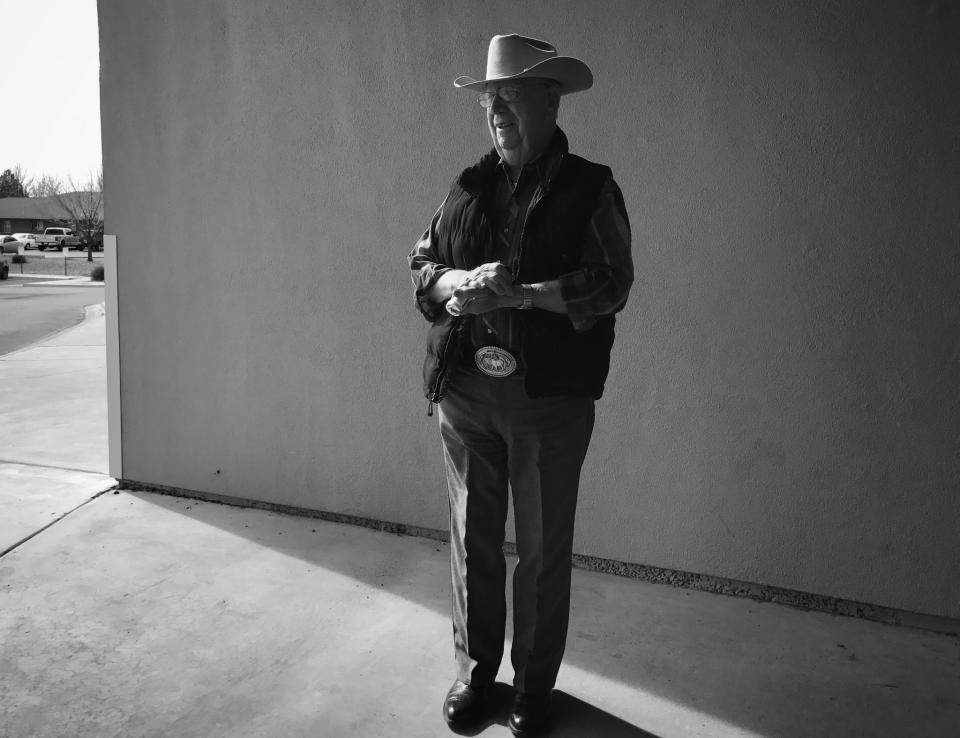

Sisson, 65, a retired Navy veteran who is now mayor of Delta, volunteers every week in the emergency room at Delta Memorial. A “gofer,” he helps with paperwork and runs errands for staff when they are overwhelmed, giving him unique insight into its operations.

Working at the hospital for nearly 10 years, he often recognizes familiar faces — elderly members of the community who have come to rely on the hospital and its companion clinics as their major source of medical care. And in recent years, he has seen many new ones: younger, mostly poor residents who went for years without adequate care but have been newly insured under the provisions of the Affordable Care Act.

“I’ve never seen the place busier,” he said.

Although doctors have credited the ACA with giving medical care to people who desperately needed it, President Barack Obama’s signature health care bill has been a sore subject here, widely reviled by people in this mostly Republican county, where many fiercely adhere to conservative values, including smaller government. Though many now have health care for the first time, and seem to like it, they also resent being told what to do by bureaucrats far removed from their daily lives.

More than two-thirds of voters in Delta County backed Donald Trump’s unlikely bid for the presidency — by one of the highest margins in the state — in part because of his pledge to repeal and replace Obamacare. The election came amid complaints of skyrocketing premiums that made the bill’s mandated health insurance increasingly hard to afford in this part of Colorado. While the bill envisioned a marketplace with robust competition, Delta County residents who signed up for the health exchange had just one provider to choose from in two of the four coverage options last year. At the same time, premiums in the county jumped an average 36 percent, according to the Colorado Division of Insurance — one of the highest increases in the state, which saw a large jump in costs.

“You had Trump saying he’s going to replace (Obamacare) with something better, and people who can barely afford to pay the bills liked that,” said Sisson, who backed the New York real estate mogul’s campaign. “Who wouldn’t go for that?”

At the same time, many people here also admit to conflicted feelings about the law. They are pleased that more people are insured, especially in an area where many residents suffer from such chronic conditions as lung disease and diabetes. They are also glad that it has stabilized the once-turbulent finances of Delta Memorial, a hospital considered vital to the region not only for medical but for economic reasons.

In addition to caring for an aging, largely poor population, Delta Memorial, like many other rural hospitals around the country, has been an economic mainstay of the community, providing employment in a town that has struggled to recover from the loss of mining and agricultural jobs. With a staff of more than 600 and an annual payroll of roughly $31 million, the hospital is easily the largest employer in the region. “I don’t know what we would do without the hospital,” Sisson said. “I don’t know what we would do if they weren’t here to take care of us. And I don’t know what we would do if we were to lose those jobs.”

Although Trump frequently said on the campaign trail that he would leave Medicare and Medicaid alone, recent developments have given Sisson and other community leaders cause for concern.

After years of operating on the brink because it treated uninsured residents who were unable to pay their bills, Delta Memorial was able to shore up its finances under the ACA, thanks in large part to a provision in the bill that allowed states to expand Medicaid to grant coverage to millions of low-income adults who could not otherwise afford health care.

Thirty-one states, including Colorado, opted into the plan, where, until 2016, the federal government reimbursed 100 percent of health care costs for those who qualified. Under the ACA, the federal government was scheduled to continue reimbursing those costs at a rate of 90 percent starting this year and beyond, with states making up the rest. An estimated 1.4 million of Colorado’s 5.5 million residents are covered under the state’s Medicaid plan. That includes roughly 500,000 people covered under the expansion granted by Obamacare, which extended eligibility to individuals and families with income of 138 percent of the federal poverty level, which is normally set at $11,880 for individuals or $24,330 for a family of four.

But the Medicaid expansion would be eliminated under legislation due to be taken up as early as this week by Congressional Republicans seeking to deliver on their long-stated pledge to repeal Obamacare. The American Health Care Act, endorsed by Trump, would not simply roll back the individual mandate for health coverage, but cut the Medicaid program by $880 billion, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The Medicaid expansion would end by 2020, and, as the bill stands now, the government would replace blanket federal aid with a set amount of spending per person.

While Trump and his GOP colleagues have described this as a chance for states to take direct control of health care and tailor it to their specific needs, critics say it would substantially reduce Medicaid coverage, sending some low-income Americans back into the ranks of the uninsured. And that, in turn, would place a greater burden on hospitals, especially rural providers, which would once again be forced to shoulder the burden of uncompensated care.

“We are facing the prospect of potentially seeing some of our funding or reimbursements go away, but the patients would not,” said Jason Cleckler, Delta County Memorial Hospital’s chief executive officer. “People will still show up, but they will show up sicker, because they don’t have insurance and haven’t been receiving preventative care. Cuts don’t lead to better access or better treatment. It drives up costs. … And the uncertainty for us and any health care provider is: How do we make up for that? It will drive up costs for everybody, and we simply can’t afford it.”

A study issued last week by the nonpartisan Colorado Health Institute found that Colorado stands to lose upwards of $14 billion in federal funding between 2020 and 2030 if the Medicaid expansion ends. Roughly 600,000 people would lose Medicaid coverage in the same period — a group that includes the elderly, blue-collar workers and low-income rural voters, all voting blocks that solidly went for Trump.

According to the Colorado Hospital Association, at least eight hospitals in the state could be at risk of closure — almost all in rural areas that backed Trump. On the list is Delta Memorial, where Cleckler described the proposed rollback of Medicaid as potentially devastating for a community that has already lost too much. While the hospital is safe this year, he said, the future is “uncertain” with any potential cut in Medicaid funds and other financial changes in the rollback of the ACA.

“I can’t think of anybody who thinks the ACA was perfect, but we can’t go back to the way things were,” Cleckler said. “We just can’t afford it.”

The threat of losing the hospital has prompted handwringing among Trump supporters here who are torn between wanting to see Obamacare overturned but Medicaid spared. Many can’t believe Trump would champion a bill that hurts the very people who so strongly supported his campaign for president. Though few openly admit it, some privately fret that their vote could take away a hospital they desperately need.

“In the back of people’s minds, it’s there, but nobody wants to say it,” Sisson said.

It’s easy to see why Trump’s message resonated in a place like Delta. Located about an hour southeast of Grand Junction and roughly five hours west of Denver, Delta is exactly the kind of forgotten place the New York billionaire frequently invoked during his insurgent bid for the White House.

Nestled in a rolling valley surrounded by soaring mountains to north, south and east, and picturesque canyons to the west, Delta, like many small towns, has been struggling to survive. Heavily dependent on agriculture, it used to have a milk plant and a sugar-processing facility, but both closed years ago. Coors used to process barley for its beer at a facility just outside town, but it, too, left years ago, consolidating operations elsewhere.

Yet the worst losses have come in the last three years, as Delta County, once the thriving heart of Colorado’s coal industry, saw two of the state’s biggest mines shut down, with the loss of more than 1,000 jobs. It was a significant blow for a county of just over 30,000 residents, especially since these were some of the highest-paid jobs in the coal industry. The laid-off miners were earning more than $80,000 a year, well above the county’s median income of $33,000 a year. Many left town, while others simply retired. As a result, Delta County’s tax revenues reportedly dropped by nearly 20 percent.

According to Sisson, many residents blamed Obama’s “war on coal” for the mining industry’s decline here — although the rise of natural gas also played a major role. But Trump, who campaigned in Grand Junction and Durango, south of Delta, in the final weeks of the campaign, still saw an opening. “You have Trump come in, promising that he’s going to bring coal jobs back,” Sisson said. “People felt hope again.”

In some ways, Delta was a microcosm for nearly all of Trump’s leading issues during the campaign. In addition to Obamacare and coal jobs, people here were upset about illegal immigration, which they blamed for an influx of crime and especially drugs. Last year, drug overdoses in Delta County were among the highest in the state, mainly due to a spike in heroin and opioid abuse — an epidemic Trump repeatedly mentioned on the campaign trial, vowing to do something about it.

At Delta Memorial, officials were stunned last year to see the number of emergency room visits from patients with mental health and drug issues outpace trauma visits. Suicides in the county are currently at record levels. Cleckler, who got his start in health care as a psychiatric nurse, has made it one of the hospital’s chief missions this year to tackle what he describes as a “total crisis” that he worries could overwhelm the hospital as it faces potential budget cuts under the GOP health care plan. Many mental health patients, he said, tend to have “little insurance or no insurance,” but they have nowhere else to go, and he said the hospital has a moral responsibility to help them.

“In the rural environment, there’s still a real stigma around dealing with mental health, so we don’t have a lot of resources like counselors and clinics. … If someone comes to us needing to be stabilized, we don’t have a lot of inpatient beds, so they might end up spending four or five days in the ER, which really isn’t what the ER is for, but there’s nowhere else to send them,” Cleckler said. “It really falls on us.”

The uncertainty around Medicaid funding comes amid larger concerns about the fate of rural hospitals around the country that were already burdened with rising debt associated with the number of the uninsured and other economic factors. Since 2010, 78 rural hospitals around the country have shuttered. And a recent study by the National Rural Health Association found that another 670 rural hospitals — roughly one-third of all rural hospitals in the country — were at risk of going under. That was even before the latest developments in Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act.

In Delta, word that the local hospital might be at risk prompted some nervousness but mostly disbelief among patients who streamed in and out of the facility on a sunny afternoon last week. Many had voted for Trump in November, although some didn’t want to believe he was really backing the House GOP bill as presented.

“That doesn’t sound like him,” one woman, a Trump voter, protested.

Indeed, Trump, before clinching the GOP nomination, repeatedly vowed to save entitlement programs, including Medicaid. “Save Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security without cuts. Have to do it,” the New York billionaire declared in a speech announcing his candidacy at Trump Tower in June 2015.

And he repeatedly trashed not only his Democratic rival, Hillary Clinton, but also establishment Republicans including House Speaker Paul Ryan, telling voters they were looking to “slash” and “knock the hell” out of entitlement programs — while he would “save” them. “’I’m not going to cut Social Security like every other Republican, and I’m not going to cut Medicare or Medicaid,” Trump told the Christian Broadcasting Network’s David Brody, a sentiment he reiterated on the campaign trail.

Trump, desperate to deliver on his campaign-trail promises and to lock up a significant political victory, appears to have hedged, aligning with Ryan, who has long argued for combining a health care overhaul and major entitlement reform. Still, pressed on the issue last week on Fox News, Trump insisted he was looking out for his supporters. “We will take care of our people, or I’m not signing it,” he declared.

It’s not clear that the bill will make it to Trump’s desk as is. Many Republicans in the Senate have raised concerns about the House GOP legislation, including the rollback of the Medicaid expansion on the poor. Among those sounding the alarm: Colorado Sen. Cory Gardner, one of the GOP’s leading advocates for a full repeal of the Affordable Care Act. Gardner, who is from rural Colorado, joined moderate Republicans including Maine’s Susan Collins on a letter earlier this month that questioned whether the Medicaid provision might be going too far.

In Delta, Cleckler spent the week trying to educate members of the community about what could be at risk for the community in the House GOP bill. And as he had for years, he found confusion among local residents. One man told him he wanted to keep the Affordable Care Act but get rid of Obamacare. “I get that a lot,” Cleckler said. “Obamacare has become such a derogatory term. I think most people don’t know what is even in the Affordable Care Act. I don’t even know all of the provisions, it’s such a massive bill.”

Outside the front entrance, an older gentleman named Bob walked up clutching his left wrist. A farmer who lives about 20 minutes outside of town, he had aggravated an existing wrist injury while driving cattle back on his ranch. A widower, he lives alone and had struggled to drive his truck into town so a doctor could take a look at it.

He shook his head as he talked about the prospect of having to go farther for care if something were to happen to the hospital. “When you’re hurt, you can’t go that far. You just can’t,” he said. “Not when you’re really hurt. Not when you’re as old as me.”

Read more from Yahoo News: