Jake has had 2 moms for years. But he was 28 before a judge made it official

As the adoption loomed, the day she would legally become the mother of her 28-year-old son, Tina Makris felt in equal parts excited and uneasy.

The feeling felt familiar for Makris, a musician.

"The whole day before, I felt like I was in prep mode for a big gig. You dig?" said Makris, who sprinkles her conversation with her own grace notes.

"I knew this was a big deal," she said. "I also knew there was a good chance that we would get some pushback, somehow, somewhere, in the process."

Makris, who's 56, and her wife, Kim McCormick, who's 57, had come to expect barriers and bureaucratic obstacles over the years, both as lesbians and as the mothers of their son, Jake.

McCormick gave birth to him in 1994 and, in 2004, Makris joined the family, raising Jake as her own. But adoption wasn't possible, at first legally, then financially, and then for thorny life reasons.

But finally, they had a date: Dec. 12, 2022.

"She felt like it wasn't going to happen," McCormick said. "That something was going to happen to prevent it."

"I think it's conditioning, right?" Makris added. "I think it's bad tapes in my head."

On adoption day, the Apache Junction couple drove to the Pinal County courthouse in Florence. Jake arrived on his own, emerging from his car looking confident, clutching a bouquet of flowers for Makris.

"And he hugged me and he kissed me on my head, so I knew everything was going to be alright," Makris said. "But I was still ready. I was armored up."

It may not have looked like an ordinary adoption, but for this family, it was meant to be.

A chance meeting, then a connection

Makris and McCormick tell their origin story in overlapping sentences, finishing each other's thoughts, occasionally stopping to debate how something actually happened.

They first met in the early 1990s at a Phoenix women's bar called Ain't Nobody's Bizness, where Makris was playing a gig.

"I looked out over the audience and it's like all I saw was her," Makris said. "And I thought, 'Wow. She's way out of my league.'"

They were introduced during a break in the music. McCormick was dating someone else, and they went their separate ways that night, but remained in each other's orbit.

A decade later, both of them were single and on a lesbian dating website, though not entirely by their own hand. McCormick was signed up by a friend at work, and Makris by her teaching assistant.

They matched, but didn't know it at first. The website was largely anonymous, with neither names nor pictures, and it wasn't until they arranged a phone call that they realized who the other was.

"You asked me if I was Tina Makris," Makris said.

"No," McCormick said. "I said, 'I think I know you'." And she did.

They went on a date to a Chandler restaurant and have been together ever since.

"It was a done deal for me," Makris said.

"It was pretty much a done deal," McCormick agreed.

Making a family, but still in legal limbo

McCormick had always wanted to be a mom. She had planned to adopt, but when she and her then-partner attended a public information meeting in the early 1990s, they were told it wasn't legal.

"They kind of paused and said, 'We just need everyone here to know, you're only eligible if you're a heterosexual couple,'" McCormick said.

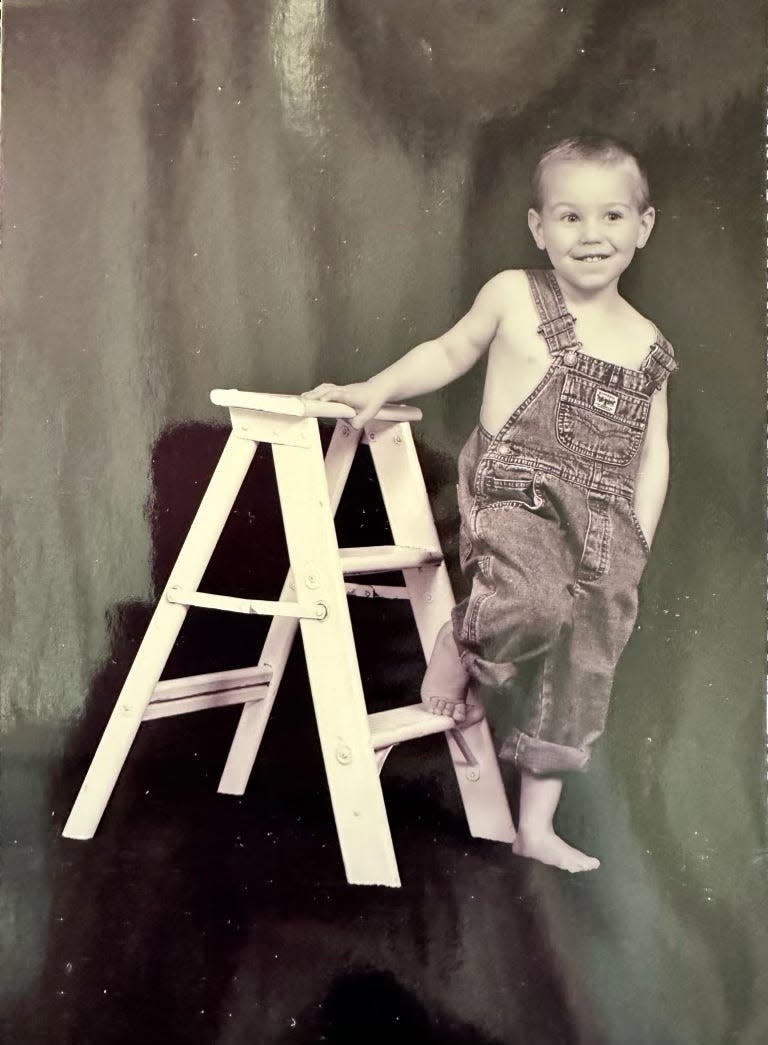

She looked into artificial insemination, and conceived Jake with sperm from a California donor. When he was one and a half, her partner left and she became a single parent.

Makris had also looked into adoption and hit the same dead end. She considered having a baby, but it didn't feel right to her. Both her parents and her brother had stepchildren, so she knew that was an option.

She wasn't out there looking for a woman with kids, she said. She had other life goals.

"I just thought, if it's meant to be, it's meant to be."

And then McCormick and Jake came along.

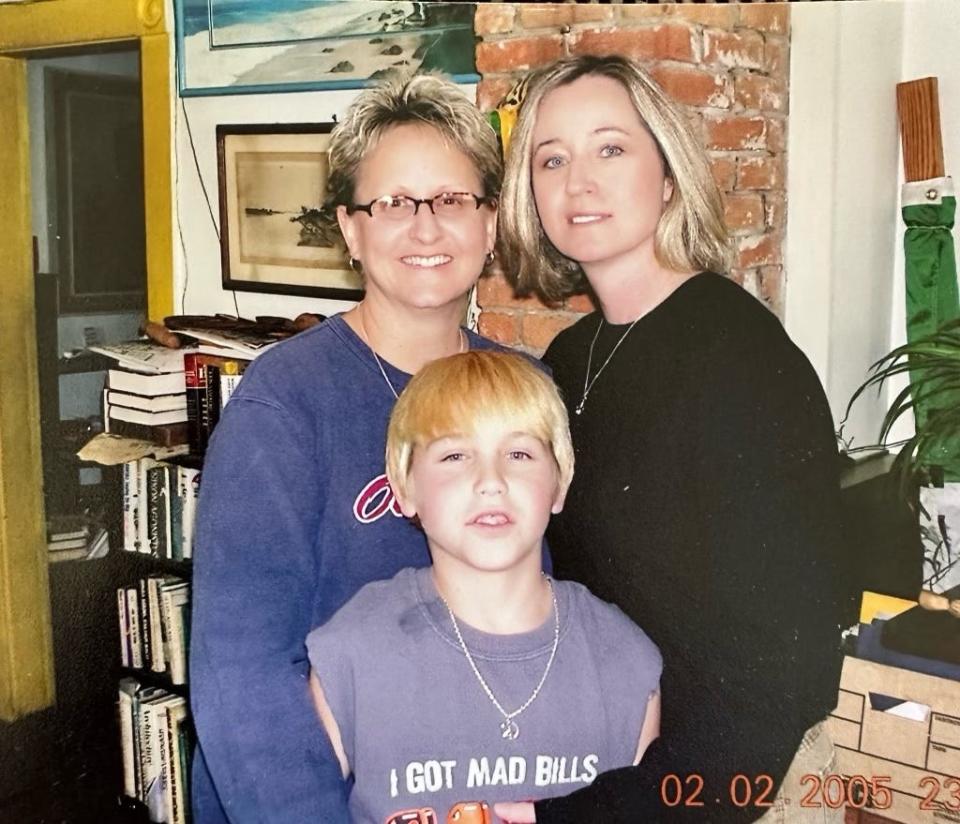

Pretty soon after their first date, McCormick brought Jake, then 9, to lunch with Makris. The three of them moved in together in October 2004.

Growing up, Jake said, he didn't know any other kids with gay parents. Sometimes he'd make friends and all would be rosy until they found out about his moms. He remembers a best friend in Mesa, a boy who lived down the block.

"When his mom found out my mom was a lesbian, she told me I couldn't play with her son anymore," he said. "So I went home and told (McCormick), and she stormed out down the street and had a discussion with her and we ended up playing together after that."

Luckily, McCormick said, Jake was an independent, forward-thinking kid. "He's always challenging the norm," she said, "and I think we gave him something else to challenge the norm about."

In 2005, Makris and McCormick entered into a civil union in Vermont. It would be years until same-sex marriage was legalized in Arizona, their home state, and in Indiana, where they spent the 2010s. Still, they were a family.

But there was a constant undercurrent of anxiety about the lack of legal relationship between Makris and Jake. The worry was always there that if something happened to McCormick, Makris wouldn't get custody, and in later years, that she could not make important decisions if ever faced with them.

The couple did what they could, making sure they always met the principal and teachers at Jake's school. Makris would take her musical performance groups there so everyone knew who she was.

"I could not make a decision for him," Makris said. "And he was so young, he probably had no idea, but those were things we had to keep at the forefront."

Drifting apart, then reuniting with purpose

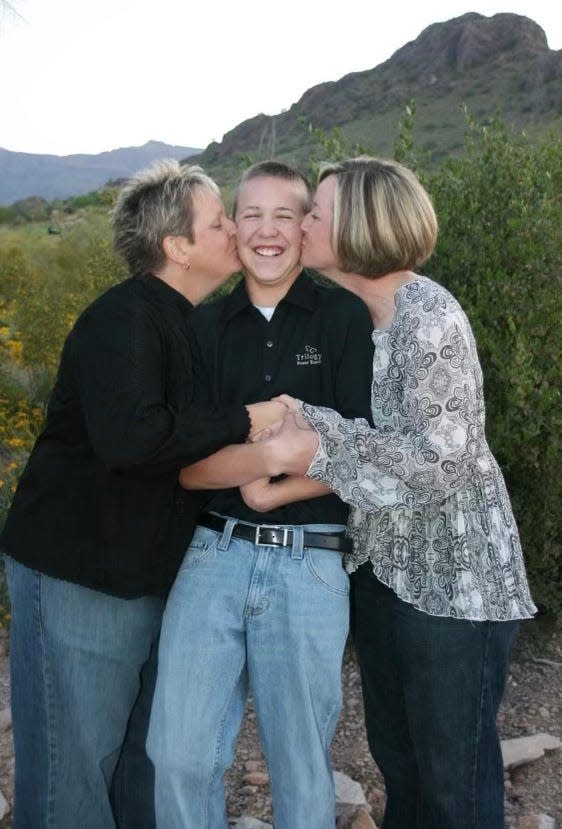

By the time same-sex marriage was legalized in Arizona in 2014, clearing the way for people in same-sex relationships to seek step-parent adoptions, Jake's life had changed a lot.

His girlfriend got pregnant in their final year of high school. He married her, left to join the Army and became a dad in quick succession.

It was the start of a long period of distance, both physical and emotional, between him and his moms. He was away for seven years, deployed three times in Afghanistan and Kuwait.

Meanwhile, Makris and McCormick were in Indiana, bonding with their new grandson, Will. Though Jake was gone, it was a profound family experience.

For Makris, it felt like catching up on what she had missed during Jake's early years. "I was able to be his parent through Willie," she said. "And that kind of brought that together."

When Jake left the military, he moved to Dallas. He felt directionless, with no vision for his life. He spent his days partying, working, only occasionally talking to his moms.

"I was at a loss," he said. "I was in the worst physical, emotional, financial state of my life."

A year and a half ago a coworker suggested he attend an ayahuasca retreat near Playa del Carmen, Mexico. Jake said his experience with the plant-based psychedelic changed the trajectory of his life.

"It was a great awakening, where truly, I found God," he said. He was consumed with an overwhelming sense of gratitude to his moms, he said, and realized the weight of the separation between them. "In that moment I decided, I need to go back to Arizona, to reconnect with them, and find myself."

Three weeks later, he had quit his job in Texas, sold or given away pretty much everything he owned, and arrived in Arizona with his dogs. He had landed on a vision for his life: becoming a pilot, and, ideally, flying for a nonprofit one day.

He structured his life around this new goal, long days spent working at a Phoenix restaurant, lifting weights, and studying for flight school, with reading, meditation and hiking in between. Now, he is entering flight school full-time.

"I'm trying to go deeper and deeper to find the best form of myself," he said.

After returning to Arizona, he saw his moms regularly. Adoption had become legal and affordable since Jake was younger, so Makris and McCormick sat him down and suggested they finally go through with it.

"We said, 'Jake, it's your call. Is this something you want?'" McCormick said. "'And if not, it's OK.'"

It was a brief conversation.

Jake said he didn't have to take a beat, to deliberate yes or no. To him, the timing felt perfect. It coincided with his big life transition, his renewed relationship with his moms.

"It just made so much sense," he said.

On adoption day, a final wrinkle

Back at the Pinal County courthouse, the first problem was that they weren't on the list. No Makris-McCormick adoption was visible on the monitors in the lobby or upstairs by the courtrooms.

A lady at the registrar's office told them they were on the docket, and directed them to the courtroom. There, they discovered they were the only ones appearing in person, other than the judge, court reporter and clerk.

The three of them clustered together on courthouse chairs and listened to case after case, remotely over audiovisual link. Then the judge called them forward.

Makris and Jake sat down at the table in front of him, while McCormick stood behind.

"And he said, 'I'm really sorry, but I can't help you,'" McCormick said. "He said 'I know you filed all this, but in Arizona, the statute says you cannot adopt anyone over the age of 21.'"

McCormick had been trying to stay out of it, knowing this moment was about her wife and their son. But she had done her research. She knew it was legal to adopt an adult over the age of 21 in Arizona, so long as the adoptee is your stepchild (or niece, nephew, cousin or grandchild). And she and Makris were legally married.

They fit the criteria. She was sure of it. So she raised her hand and explained that to the judge.

"I thought, we all thought, he's going to dismiss us for now, do his research and we'll come back," McCormick said. "But no, he gets right on his computer and he's looking."

The three of them waited while he checked the statute.

"I’m sorry," the judge said. "You’re right.”

He asked Makris and Jake why adoption was important to them. He checked three times that Makris and McCormick were legally married.

And then he said he would grant the adoption.

But relief didn't flood in just yet. They were sent back down to the registry to get the court order. It didn't materialize. They stuck around for hours, before a woman at the desk told them it appeared to have been mislaid, that she would track it down and send it via certified mail.

They left the courthouse, convinced something would go wrong. The paperwork would never turn up. The judge would change his mind.

"Until we got it in the mail," Makris said, "we didn't believe it."

'It's a grown man!'

And that's how Jake McCormick became Jake Makris McCormick.

In late January, more than 100 people crowded into the Forum in Chandler to celebrate the successful adoption. The event started out small but quickly ballooned as people in the community found out what was happening and offered their help. The venue donated a DJ, a chef donated food, a photographer their time, a florist some beautiful blooms.

The event elicited some creative gifts. A friend gave Makris a framed, wood-burned plaque, styled to look like a birth announcement, but with the adoption date instead and the declaration: "It's not a boy, it's not a girl, it's a grown man!"

McCormick and Jake gave Makris a bronzed Vans sneaker, a nod to the shoes his moms would buy him every year on his birthday growing up. A tag dangled from the preserved slip-on shoe: "Jake Makris McCormick. It's official! Dec. 12. 2022."

For McCormick and Makris, who spent years anxious about the legal status of their family, the community support felt hard to believe. They're surprised at how quickly times have changed.

"It shows the evolution of the country, a snapshot of how it is evolving in places, I guess," McCormick said. "But it's still shocking. I'm overwhelmed."

For McCormick, who describes herself as more of a "practical and analytical" person, it's a great relief the three of them are all legally connected. The custody worries are gone, but now that she and Makris are older, she said, Jake can step in as the legal child of both if decisions ever needed to be made on their behalf.

For Makris, the adoption brought up some unexpected emotions. Both she and Jake were clear that it was about making an existing connection legal, that she was his mom before and after a judge made it so. She didn't think it would change that much.

"From my perspective, though, I just feel more of a closeness with Jake," she said. "Even text-messaging with him, chatting with him … it's just a little different. Even when I think of our grandson Will, it's just different.

"And I wasn't expecting that at all."

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Jake's 2 moms made their family legal years after it was real