After Jan. 6 riot, hundreds of identifiable people remain free. FBI arrests could take years

It was the opening melee of the Jan. 6 insurrection. As the first rioters forced their way onto the Upper West Plaza of the Capitol, they turned to face the crowd of thousands, gesticulating to follow and screaming at the police to retreat.

Rioters threw sticks and projectiles at officers. Flagpoles pounded on the ground. Smoke rose. Someone wearing a bald eagle head and star-spangled suit wandered through the chaos.

As Capitol Police officers wrestled knots of rioters, trying to hold back the horde, videographers captured the scene. In the videos, a man can be seen from several angles picking up a large canister of pepper spray from the ground. The man fires a jet of spray at protesters and police officers. As he drops the canister and walks away, people all around begin to cough.

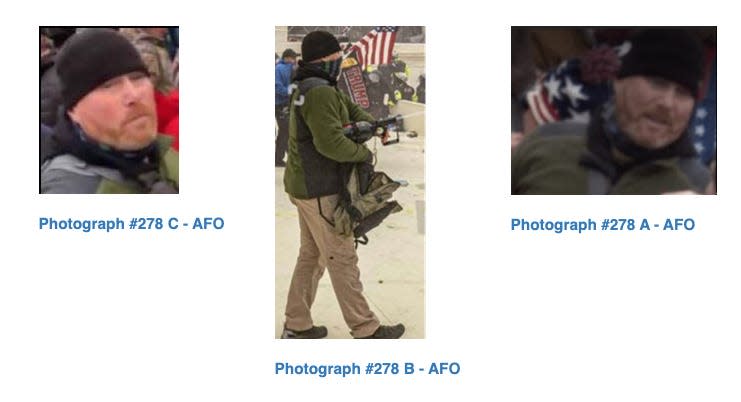

That man, like hundreds more, is wanted by the FBI. Three photos of him appear in the FBI’s online photo gallery of people wanted in the insurrection. Two photos show his face while a third shows him wearing a face gaiter, the pepper spray canister in hand.

He is identified only as suspect #278 AFO. AFO stands for “Assault on a Federal Officer.”

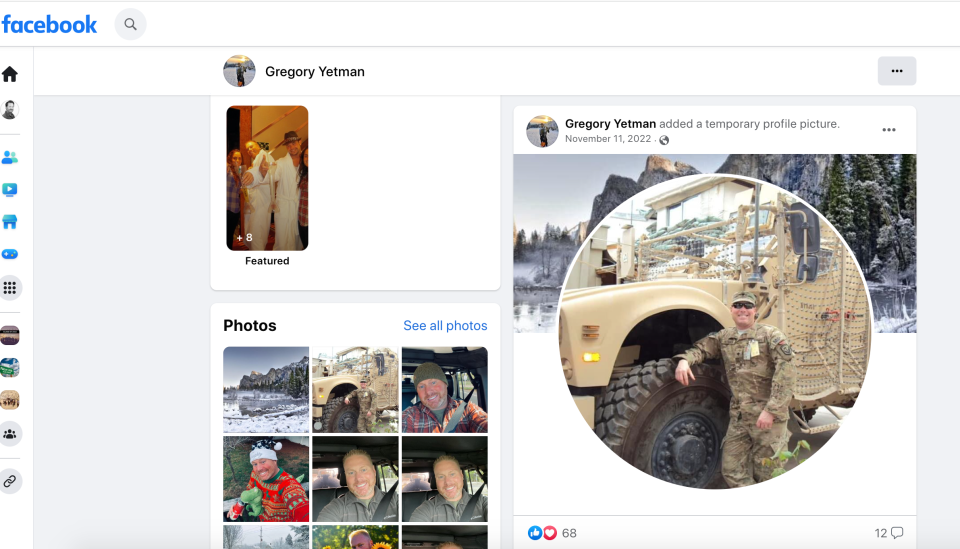

USA TODAY interviews and a review of online video and social media – based on information supplied to the FBI by an army of online sleuths – all point to one man who admits he was at the Capitol that day: Gregory Yetman.

At the time of the insurrection, Yetman was a military police sergeant in the New Jersey National Guard. He continued to serve until he was honorably discharged in March 2022.

Online researchers provided Yetman's identity to the FBI more than a year ago, but he has never been arrested.

Yetman insisted in an interview with USA TODAY that he did nothing wrong that day at the Capitol and says he didn't pepper-spray anyone.

Cases like 278 AFO illuminate a lesser-known underside of the effort to arrest and convict people responsible for the insurrection. While federal officials have publicized the prosecution of nearly 1,000 people in the Jan. 6 investigation, far less focus has been placed on the hundreds more who are wanted but have never been charged.

Cases examined by USA TODAY show just how definitively many of those suspects can be identified. Indeed, more than 100 suspects wanted by the FBI have already been named by groups of online researchers known as "sedition hunters."

One activist group says it has provided more than 100 identities of people on the FBI’s wanted list to the bureau, as well as tips about hundreds more who aren’t on the list but were allegedly caught on camera committing crimes.

An online database maintained by another group details 105 wanted suspects whom it claims have been identified to the FBI but not yet arrested.

“The amount of information the Sedition Hunters give the FBI – it’s a portfolio of information,” said Forrest Rogers, a volunteer investigator who has been researching the Jan. 6 riot for two years. “We give them everything but the longitude and latitude coordinates of their house.”

The reasons these suspects remain free are unclear. The FBI and Justice Department won't comment specifically on where those cases stand. What is clear is that the rate of prosecutions has declined sharply since the early months of the investigation.

In some scenarios, the legal mandate for a speedy trial may be leading prosecutors to wait to file charges. Once an indictment lands, the trial deadline arrives quickly – perhaps too quickly given the historic number of cases already clogging the courts.

At the same time, the online sleuths who have seen their earlier tips lead to convictions are now growing frustrated as they see many suspects remain free while other people are convicted for seemingly lesser crimes.

A former federal prosecutor told USA TODAY it's not unusual to file charges years after the fact, up to the very day the statute of limitations runs out. So, while hundreds of suspects may now carry on about their daily lives across the United States, a flood of arrests may still be on the way.

“It’s valid to raise the question that there are people who've been identified pretty conclusively but haven’t been picked up yet – that's a fair question to ask,” said Patrick Cotter, a former federal prosecutor in Chicago who has practiced criminal law for 40 years.

But Cotter cautioned against concluding the agency won’t act. “The fact that he hasn't been picked up yet, or charged,” he said, “doesn't mean he's not on the government's radar.”

See every arrest: USA TODAY's database of Jan. 6 riot charges

The search for Suspects 278 and 119

USA TODAY independently corroborated the identities of six people depicted on the wanted list – people the Sedition Hunters say have already been reported to the FBI, some more than a year ago.

One of the three photos of suspect 278 AFO on the FBI’s wanted list shows the pepper spray incident. In that photo, a man wearing a black beanie and distinctive striped face gaiter fires pepper spray across the outdoor plaza toward police and protesters.

In the other two FBI photos of suspect 278, the man’s face is clearly visible.

The Sedition Hunters said they used facial recognition software to match the suspect’s face to photos of Yetman. In numerous photos on Yetman’s Facebook page, he is wearing the same black beanie or distinctive face gaiter as the man who can be seen firing the pepper spray canister.

The FBI’s wanted list says it depicts people “who assaulted federal law enforcement personnel.” But it doesn’t specify what each person allegedly did that constitutes a crime.

In interviews with USA TODAY, Yetman admitted being at the Capitol riot but said he isn’t the man caught on video spraying pepper spray. USA TODAY sent Yetman copies of the FBI photographs of suspect 278 and asked if they are pictures of him. He didn’t respond.

Yetman told USA TODAY the FBI interviewed him in January 2021. He said he has never heard from the bureau since.

“Everything’s been resolved, everything’s good,” he said.

Suspect 278 was dubbed #HeavyGreenSprayer by the sedition hunters, who assigned individual hashtags to the hundreds of suspects they investigated.

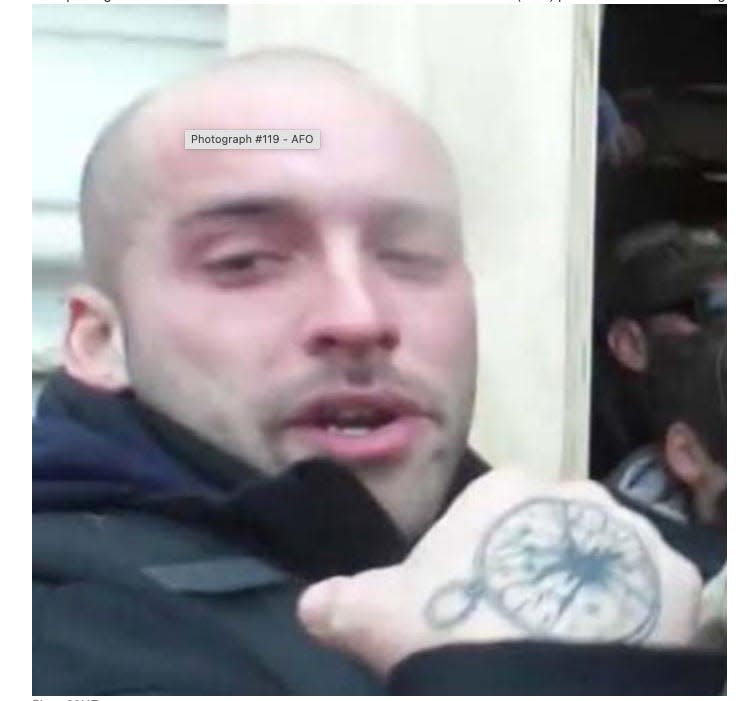

Another man they hunted was #ShinyCircleTattoo, suspect #119 AFO on the FBI’s wanted list and so labeled by the volunteer researchers because of a circular tattoo of a compass on the back of his right hand.

As with suspect 278, the FBI’s entry doesn’t specify what acts constitute suspect 119’s alleged crime.

But online sleuths identified the man with the uncommon tattoo as Logan Tate, an insurance agent from Kentucky, who had posted photos and videos from the Jan. 6 Capitol riot on social media. The Sedition Hunters say they spotted Tate in videos taken in a crowded tunnel leading into the main Capitol building.

According to their video review, a person with the same body art appears during key moments of footage.

In one, the man can be seen among a mob of rioters pushing against a wall of police officers while people shout “Heave, heave.” In another video, apparently taken shortly afterward, he emerges from the tunnel, his eyes watering, presumably from tear gas. He’s still carrying the object and is wearing a protective vest.

In an interview with USA TODAY, Tate didn’t deny being at the Capitol. He acknowledges FBI photo #119 AFO is his picture.

He said he was on the upper deck of the Capitol, but said he never entered the building or assaulted anyone – disputing the “AFO” status.

“I would never hurt an officer. I come from a military background, I'm very respectful of our military and police,” Tate said. “I know I didn't hurt anybody – I'm not speaking here bold as brass, because you never know what can happen – but I've never, ever once hurt, or put my hands on an officer.”

He said agents interviewed him a few days after the insurrection. They took his phone, he said, which still contained the videos from the day, and he hasn’t heard from the FBI since.

He said he doesn’t know why his photo is still on the FBI website.

“If I’m on that list for the rest of my life, I guess I'll be there,” he said. “But I never did it. So I'm not going to live the rest of my life in fear.”

In addition to suspects 119 and 278, USA TODAY similarly corroborated the identities of four other suspects provided by the Sedition Hunters, using FBI photographs, archived video, social media posts, a variety of public records and interviews.

Those people are two men given monikers referring to their “crowd surfing” of the rioters as they attacked police; another man seen unmasked on camera pepper-spraying police officers; and a man who the Sedition Hunters say was one of the first, if not the very first rioter, inside the Capitol.

According to Justice Department reports, none of those people has been arrested.

Rate of new cases has slowed

The Justice Department has not publicly said how many people it plans to prosecute for Jan. 6. On the second anniversary of the riot, Attorney General Merrick Garland said:

“We remain committed to ensuring accountability for those criminally responsible for the January 6 assault on our democracy. And we remain committed to doing everything in our power to prevent this from ever happening again.”

The time frame for that commitment, though, is less clear.

A USA TODAY analysis found the rate at which the Justice Department filed charges against Jan. 6 defendants has dropped off precipitously since the first six months after the insurrection. Prosecutors charged 566 people from January to July 2021. In the 18 months since, just 404 people have been charged.

Federal authorities say there are many reasons for the delays in bringing suspects to justice.

Chiefly, they stress this is the largest investigation the FBI has ever done and say cases amateurs may see as open-and-shut often prove difficult to prosecute beyond a reasonable doubt.

In his statement marking the second anniversary of the insurrection this year, Garland highlighted the record number of cases brought before the courts.

“Countless agents, investigators, prosecutors, analysts, and others across the Justice Department have participated in one of the largest, most complex, and most resource-intensive investigations in our history,” he said. “This investigation has resulted in the arrest of more than 950 defendants for their alleged roles in the attack.”

But Michael Sherwin, a former high-ranking U.S. attorney who headed up the original effort to prosecute Jan. 6 rioters and left the Justice Department in April 2021, said that’s not a reason to delay further arrests.

Sherwin acknowledges the insurrection left the Justice Department with a mountain of prosecutions to process. But, outside of a handful of more complex seditious conspiracy cases, he said the work to be done to bring rioters to justice was not all that complicated.

“Look, this is a significant time in DOJ history. It is unprecedented in terms of the scope of the investigation – the size – but in terms of the cases, it's really not, because in general, they're pretty pedantic, basic cases,” Sherwin said.

More: Oath Keepers founder, found guilty of seditious conspiracy. What that means

Cotter, the former federal prosecutor, said that just because suspects listed as wanted by the FBI haven’t been arrested two years after their alleged crimes doesn’t mean they won’t face justice at some point.

Even at the best of times, federal prosecutors have more cases than they can possibly prosecute, Cotter said. Often, Cotter said, case filings are determined by how much time remains until the statute of limitations runs out.

For the insurrection, the statute of limitations for most of the alleged crimes runs out in January 2026.

“Every defense lawyer who does a lot of this federal work will tell you we've all had clients who were indicted literally within weeks, or even days, of the expiration of the deadline,” Cotter said. That’s not legal gamesmanship, he said, but a simple matter of resources. “It's usually done because it's just that's where the guy was in the queue.”

Now, with an influx of hundreds, if not thousands, of prosecutions related to Jan. 6, the Justice Department has had to reexamine its priorities across the country, Cotter said.

That answer doesn’t satisfy everyone. Rogers pointed out that while the federal investigation is historic in its scope, the amount of help law enforcement agencies have received from volunteers is also unprecedented.

“The FBI has never had this much support resolving cases,” he said.

Sedition Hunters' efforts

Several people connected to the volunteer effort told USA TODAY they question why it is taking so long to pick up “wanted” suspects they say they positively identified more than a year ago.

“It's incredibly frustrating when, in March of 2021, you gave the FBI a complete dossier and, two years later, you're seeing pictures of the guy on his Facebook celebrating his son's wedding,” Rogers said. “And you know that two years ago he was punching a photographer and pepper-spraying police officers.”

Volunteers also say they’re perplexed as to why some cases have been brought, while others – including ones that appear strikingly similar – haven’t.

For example, while Yetman is still walking free, three men were convicted in December for doing almost exactly what video appears to show suspect 278 doing – picking up discarded pepper spray canisters and using them in the riot.

Dozens of people have also been charged with misdemeanor crimes that appear less serious than the apparent acts of suspects 119 and 278.

It’s clear the FBI doesn’t ignore the Sedition Hunters’ tips – or at least it didn’t in the past.

Numerous federal affidavits and complaints in Jan. 6 prosecutions reference tips received from the Sedition Hunters and people who saw suspects they recognized on the group’s website or social media.

Sherwin said the volunteer investigators were certainly useful in the time he led the investigation.

“In the first 2 1/2 months, they were critical in filling the gaps with social media. These sleuths did provide great tips,” he said. “The use of social media evidence in the J6 cases is really unprecedented in terms of scope and weight.”

A ‘traffic jam’ in the courts

Cotter, the former prosecutor, stressed that U.S. attorneys would be mindful of falling afoul of a suspect’s constitutional right to a speedy trial. As soon as someone is arrested, the clock starts ticking, Cotter said.

And hurrying a case through court may be harder than ever right now.

Early in September, when Stewart Rhodes, founder of the extremist group the Oath Keepers, asked U.S. District Court Judge Amit Mehta for a 90-day extension to prepare a new attorney for his trial, Mehta emphatically denied the request.

“Jan. 6 has created a massive traffic jam” in the federal courts in Washington, Mehta said.

In at least one instance, a Capitol rioter has almost been freed because prosecutors failed to meet their deadline of bringing an indictment or criminal information against him. Texas resident Lucas Denney, who later pleaded guilty to assaulting Capitol officers, went three months without a court hearing and only remained imprisoned when prosecutors finally indicted him, despite having missed their deadline to do so.

Flooding the already overburdened D.C. federal court system with hundreds more Jan. 6 cases could, conceivably, lead to a bottleneck that could result in cases like Denney’s missing deadlines to bring suspects before a judge.

That would mean more Jan. 6 suspects right back where they are now: free.

Complicating this is the fact that a high proportion of Jan. 6 cases are going to trial rather than being settled in plea agreements.

Cotter said that in his experience, 90% of federal cases end in plea agreements. Of the 556 cases so far concluded, that rate is holding true for Jan 6, with 90% of the defendants taking plea deals.

But Jonathan Lewis, a research fellow at the Program on Extremism at George Washington University who is tracking insurrection prosecutions, said that proportion is likely to change significantly in the coming years and months.

There are many more Jan. 6 defendants who are moving toward trial, Lewis said, meaning fewer quick resolutions and more days in court.

“It should not be lost that a not-insignificant number of these defendants have retained private legal counsel who have themselves promoted discredited legal theories surrounding the attack,” he said.

Or, as Cotter puts it: “You can't make a plea deal with a guy who doesn't think he's guilty.”

More: Two years since the Jan. 6 insurrection, extremist groups are fragmented, but live on

Prosecutors proceeding with caution

Meanwhile, House Republicans are gunning for the Jan. 6 investigation. A recently launched GOP-controlled subcommittee – the Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government – will investigate claims that the FBI and Justice Department abused their investigatory powers, including in the Jan. 6 prosecutions.

But while House Republicans suggest federal law enforcement has already gone too far, the agencies themselves have asked for more resources. Justice Department sources told NBC News last year that extra funding to work on the Jan. 6 cases was “critically needed.”

Congress addressed that in the federal spending bill passed at the end of last year, allocating an extra $212 million to U.S. attorneys across the country in part “to further support prosecutions related to the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol.”

Cotter said the new funding should be welcomed. Though he doubts individual prosecutors will feel threatened by the congressional posturing, he said the pressure will be on U.S. attorneys to ensure every case they pursue is as watertight as possible.

“It can't help,” Cotter said. “Even if they think the attacks are baseless, even if they think the arguments that they've been weaponized by Democrats to go out and, and go after Republicans – even if they know that that's all complete, utter nonsense – you have to have it in your mind. And you have to say, ‘Well, we have to be extra-careful that everything we do can pass a very, very thorough inspection.’”

Contributing: Dinah Voyles Pulver, USA TODAY

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: 100-plus Jan. 6 rioters haven't been arrested. It could take FBI years