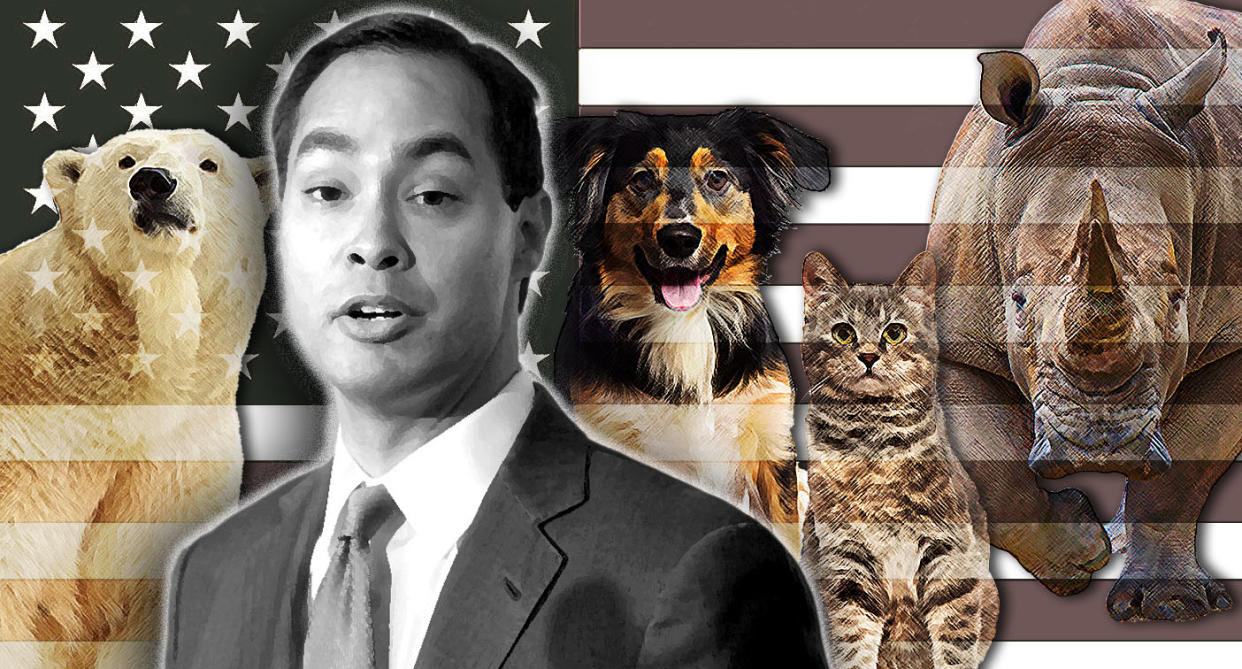

Julián Castro's plan to save the animals

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

Wild animal species, including such icons of wilderness as rhinos and tigers, are endangered. Pets and farm animals are in no danger of extinction, but need protection against cruelty.

The threats include hunters, breeders, irresponsible owners, kill shelters, poultry and fish farms, ocean polluters and the global climate crisis.

Democratic candidate Julián Castro says there are too many kill shelters, and too few humane treatment laws. Too many loopholes in the Endangered Species Act, too little attention to the finding by a United Nations panel that 1 million animal species are at risk of extinction in a disrupted climate.

“There is a special bond between people and animals,” says Castro, the former mayor of San Antonio and secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development under President Obama, and the only candidate with a specific plan addressing animal rights. Unveiling his Protecting Animals and Wildlife plan (aka PAW) last month, he said: “We have a responsibility to protect and care for them.”

Humane treatment of domesticated animals has been a cause in the U.S. since the founding of the ASPCA (American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) in 1866. Concern for wild animals and their habitat is a much more recent concern.

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 established a list of “birds, insects, fish, reptiles, mammals, crustaceans, flowers, grasses, and trees” whose futures were threatened, and protected them from “destruction.”

Individual states have taken steps to ensure more humane treatment for farm animals. California and Massachusetts, for instance, have passed public initiatives that protect farm animals — including egg-laying hens, pregnant sows and young calves — from confinement in cages and crates, and ban the sale of milk, eggs and meat from confined animals.

And animal rights activists have been pushing for lower kill rates at animal shelters, some of which euthanize as many as 80 percent of the strays they bring in.

These and other measures have been successful. Of the long list of animals, plants and insects who have been put on the ESA, 99 percent have been saved from extinction — including the bald eagle, the gray wolf, the grizzly bear and the humpback whale. The bans on sales of inhumanely raised livestock in large consumer states has resulted in better treatment of animals in producer states. And a New York Times investigation this month found that the kill rates at American shelters has dropped 75 percent over the past 10 years in the nation’s largest cities, as adoption and rescue have become more popular.

But animal rights advocates believe more should be done.

While the decrease in shelter killings is welcome, critics say it falls short of many other nations. Holland claims to have become the first country in the world to eliminate its stray dog problem; 90 percent of Dutch residents own a dog, and 1 million have been adopted off the streets.

On the other hand, farmers and ranchers object to the costs of new laws giving animals more space, costs that are passed on to consumers. Some large producing states have fought back. In Iowa, for example, a 2018 law requires that any grocer selling cage-free eggs to also sell caged eggs.

And the Endangered Species Act has been an irritant to business interests, who say protections for species such as the piping plover or the snail darter stands in the way of mining, logging, farming and development projects.

Those complaints have found a receptive audience in the Trump administration, which has unveiled regulations that significantly weaken ESA protections, reinterpreting the definition of “endangered” so that a species would not be protected until it was already nearly extinct.

The Sierra Club released a statement saying the new rules would mean a delay of “lifesaving action until a species’ population is potentially impossible to save; making it more difficult to protect polar bears, coral reefs, and other species that are impacted by the effects of climate change; allowing economic factors to be analyzed when deciding if a species should be saved; and making it easier for companies to build roads, pipelines, mines, and other industrial projects in critical habitat areas that are essential to imperiled species’ survival.”

As mayor of San Antonio, Castro oversaw the transition from the city with the highest shelter kill rate per capita to one with a no-kill policy. His PAW proposal contains protections for the kinds of pets that wind up in shelters, allocating $40 million in federal funding for programs that provide vaccinations, neutering and promotion of shelter adoption, as well as requirements that new public housing and existing homeless shelters allow residents to bring their pets.

He also addresses the welfare of animals that are not (or should not be) household pets. PAW would make it a federal crime to abuse any animal; ban the importation of big-game hunting trophies as well as private ownership of lions and tigers (there are thought to be more tigers in private captivity in the U.S. than in the wild); reverse the Trump administration’s rollbacks of the ESA; and create a $2 billion National Wildlife Recovery Fund to combat extinction threats domestically and double the U.S. contribution to the Multinational Species Conservation Fund.

So far, he is the only candidate to tie domestic pet rights, farm animal rights, wild animal rights and the climate crisis together into one package, though others have addressed the issues piecemeal.

Cory Booker, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have received perfect scores on the Humane Society Legislative Fund’s Humane Scorecard. Booker, a vegan, speaks openly but nonjudgmentally about that choice, saying it is motivated by a desire to prevent cruelty to animals but that, as president, he would not “preach to anybody” about what they “can or cannot eat.”

And author Marianne Williamson has said that abuse and mistreatment of animals has been “damaging to the American soul.” Her campaign website says: “We need to find a way to better respect animals … all the while, supporting our farmers and ranchers, financially and otherwise.”

Castro may love animals, but his reasons for highlighting their rights is less about puppies are cute than about cute puppies are potentially good politics. He is currently at the back of the pack of 10 candidates to qualify for the Democratic debate stage, and needs a way to differentiate himself.

Is this the way?

The issue has dual appeal. First, it allows Castro to directly criticize Donald Trump (the first president in modern memory without a pet in the White House) not only on policies like the ESA reversal, but personally, as his sons are known to be avid big game hunters.

“The president does not care about animals and his cruel actions prove it. He has put corporate profits over living creatures and individual fortunes over our future,” Castro said. “This groundbreaking plan will improve the treatment of animals around the country and the world, and undo Donald Trump’s damage.”

Second, Americans love animals. A Gallup poll in 2015 found that nearly a third of respondents support giving animals “the same rights as people,” (to decent living conditions, not, say, the right to vote) up from 25 percent from 2008. Only 3 percent agreed that no protection was necessary because “they are just animals.”

And Americans particularly love their own animals. The American Veterinary Association says that nearly 37 percent of U.S. households own dogs, while about 30 percent own cats, and they spent an estimated $72 billion on those pets in 2018 — more than the combined GNP of the world’s 39 poorest nations. (Some $440 million of that went toward Halloween pet costumes.)

It is far from clear, however, that focusing on pets will be the issue that Castro’s campaign needs to increase his visibility and poll numbers.

Animal rights groups, while praising his plan, are also careful to commit their support to those more likely to become the nominee.

“We applaud Secretary Castro’s proposal to protect our pets, wildlife, and animals raised for food,” Brad Pyle, the political director at the Humane Society Legislative Fund told the Washington Post. “Voters are lucky to have so many animal protection champions seeking the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination.”

Still Castro’s focus on animals means it is likely that the parade of candidate pets — which began when Warren brought Bailey, the golden retriever, on stage during her campaign kick-off event — will not abate any time soon.

Castro, ironically, does not have a pet himself. Nor does Booker, though he promised a young supporter that he would adopt one if elected. But Truman and Buddy Buttigieg (a beagle/lab mix and a puggle) have their own active Instagram account, and Champ and Major Biden (both German shepherds), Artemis O’Rourke (a black lab) and Pepper and Captain Flint Bennet (a dog and a cat) show up often in the social media of their humans.

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News: