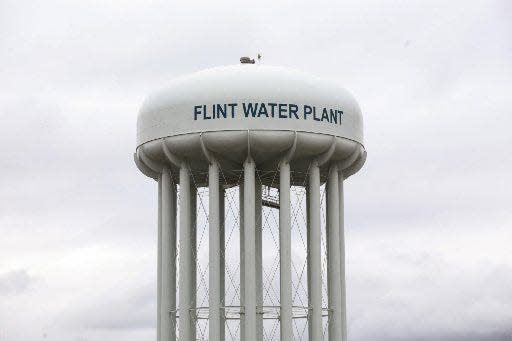

'It's just devastating': Flint reels as water crisis prosecution comes to an end

State prosecutors conceded that a Tuesday order issued by the Michigan Supreme Court declining to hear an appeal in the case against former Gov. Rick Snyder marked the end of the pursuit of criminal cases stemming from the Flint water crisis, issuing an unattributed statement calling the order “the final nail in the coffin.”

For residents and activists in Flint, the tenor of the prosecutors’ statement is another notch in what is seen as the botched handling of not only the water crisis itself, but the response of state leaders who promised to deliver justice for the people of Flint and accountability to those in power when the city’s water supply was poisoned.

“It’s outrageous, what’s happened,” said Claire McClinton, a lifelong Flint resident and retired General Motors worker. “What we’ve been saying in the community, it’s either been treachery or incompetence. And we as residents of the city of Flint are on the losing end.”

Tuesday’s order marks end of legal strategy questioned by some from the start

The state’s Flint Water Prosecution Team, led by Chief Deputy Attorney General Fadwa Hammoud and Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy, was put in place in 2019, shortly after Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel assumed office. Since the attorney general is bound to defend the state in civil litigation on the same subject, Nessel appointed Hammoud and Worthy to lead the prosecution efforts, charging nine former officials, including Snyder, former Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Director Nick Lyon, Snyder’s top aide Richard Baird and others for their roles in the water crisis.

The team tossed dozens of charges already brought on by Todd Flood, the special prosecutor appointed by Nessel’s predecessor, former Attorney General Bill Schuette. The team cited problems with the initial investigation, particularly how evidence was gathered. But the cases had appeared to be moving forward — a district judge had bound Lyon over to stand trial on charges, including two for involuntary manslaughter.

That was further than the cases brought forward by the new prosecution team ever advanced — in 2022, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled that prosecutors erred in having Genesee County Circuit Judge David Newblatt act as a one-person grand jury to indict the former officials. After the ruling, the cases were dismissed in lower courts, and efforts to appeal the dismissals were unsuccessful at each step, concluding with the state’s high court declining to hear an appeal for Snyder’s case Tuesday.

Defense lawyers for the former officials charged expressed skepticism with the state’s attempts to ask the Supreme Court to reverse dismissals of the cases that were based on their own ruling — one lawyer told the Free Press the attempt to appeal his client’s case “was foolish.”

In 2019, Nessel said in a statement to Flint residents, “Justice delayed is not always justice denied." But the decision to restart prosecution efforts was met from the start with skepticism from some in Flint.

“That was very painful because one of the things about recovering from what we’ve been through is for people to be held accountable,” McClinton said of the decision to restart the criminal proceedings.

“That's part of our recovery, to validate that we had been wronged by our government. People lost (their) lives and everything. Those that didn't lose their lives have lifelong consequences in terms of mental health, physical health, and everything else. It’s just devastating, and this is just another notch on that.”

Four years later, the end of the prosecutorial efforts has left residents wondering why there won’t be consequences for those in charge during the Flint water crisis.

“I have several questions for Attorney General Dana Nessel looking at the long-term handling of the case,” said Nayyirah Shariff, executive director of grassroots organization Flint Rising and a resident of the city. “Nobody has been brought to trial. All these folks can go off and live their life, bounce back with jobs and salaries, whereas Flint residents will be forever living with the consequences of those actions, through their bodies, through the impairment of their health.”

Prosecutors have defended their use of a one-person grand jury to bring indictments — in its statement issued Tuesday, the Flint Water Prosecution Team maligned the court’s interpretation.

“The Court decided that a process which has stood in place for over a century, one whose legitimacy the Court upheld repeatedly, was simply not ‘good enough’ to hold those responsible for the Flint Water Crisis accountable for their actions,” the statement read. “Our disappointment in the Michigan Supreme Court is exceeded only by our sorrow for the people of Flint.”

The one-person grand jury has been used to deter the “no-snitch” mentality that can arise in some cases of violent crime or to encourage witness cooperation in cases of public corruption. Shariff said she wonders why the tactic suddenly came into question for the Flint water crisis criminal cases.

“You have thousands of Black and brown people in jail, and that’s how they were indicted, a one-person grand jury,” Shariff said. “It just felt like there are two different justice systems.

“Today is kind of the death knell reinforcing the fact there is a justice system for Black and brown people, within the state of Michigan, and then there's another justice system for wealthy white men with money and power.”

Blaming the court ruling is a failure to accept accountability, some residents say

The Flint water crisis began in 2014, when the city, while under emergency management from the state, switched water sources and lead, a neurotoxin particularly dangerous to children, leached into the city's water supply. As the city struggled with water quality, it also saw an outbreak of Legionnaires' disease, leading to the deaths of 12 people and sickening dozens more. And questions remain over the long-term effects of the contamination crisis; a study backed by the federal Office of Victims of Crime found that 1 in 5 Flint residents were believed to meet the criteria for clinical depression. Researchers say the findings suggest more resources are needed to address the water crisis’s effect on long-term mental health.

Given the amount of time since the water crisis began, some residents had started to wonder if they’d ever see justice, said Benjamin Pauli, a Flint resident and the president of the board for the Environmental Transformation Movement of Flint.

“This process has been dragging on for so long that frankly, a lot of us were wondering if what the AG was really looking for here was some kind of an out, and if that's what they're looking for, that's what this is for them,” said Pauli, who is also a professor of environmental justice at Kettering University in Flint.

“They don't have to spend any more taxpayer money on this. They can point the finger at the Michigan Supreme Court and blame them, rather than taking the blame themselves for the manner in which they chose to go about pursuing these cases.”

In 2019, when prosecutors dismissed the initial charges brought by Flood, they held a community forum weeks later at which Hammoud and Worthy fielded questions from residents. That year, Melissa Mays told the Free Press that the forum should have been held before the decision was made to start the criminal proceedings over again.

“That’s when I felt justice was gone for us,” Mays, a Flint resident and activist, said Tuesday. “They threw them out — we found out through the media — and then they waited three weeks to say anything.”

Failed prosecution efforts another reason there’s no trust in government, residents say

In Flint, replacement of the corroded lead service lines remains ongoing — a judge had issued a deadline of Aug. 1, 2023, for the replacement of those lines, three years past the initial target. Michigan Radio reported in August that service line replacement was still ongoing.

As McClinton put it, seeing justice for those in power during the crisis is part of the recovery process. Residents particularly pointed to Snyder's case closing as a disappointment.

Shariff noted that much of Snyder’s campaign to become Michigan’s governor was centered on his approach to treating Michigan like a business — “If you’re looking at it in that context that Snyder is the CEO, the buck should stop with him,” she said.

Residents said it will be tough for the Flint community to trust its state government again, now that the water crisis which poisoned it has been coupled with a lack of justice for those who were entrusted to protect it but failed to do so.

“Why would we?” Mays asked. “Nobody's done anything to gain our trust. The bad pipes are still in the ground, in our homes, and nobody is being held accountable. Nobody's sitting behind bars.”

A message left with a spokesperson for Flint Mayor Sheldon Neeley wasn't returned. In a statement, Neeley echoed prosecutors in maligning the Michigan Supreme Court's interpretation that the one-person grand jury was incorrectly used, saying: "Snyder has been allowed to evade justice based on a technicality thanks to a well-resourced, taxpayer-funded legal defense. The standard of justice has not been balanced.”

In their statement issued Tuesday, Hammoud and Worthy said they plan to issue a report on their handling of the prosecution next year. But state law prohibits the evidence shown to Newblatt, the judge, from being made public. Prosecutors say they plan to work with state legislators to change the law, but Pauli said that plan doesn’t seem feasible.

He also said the failure to land a conviction in the Flint water crisis is going to deepen the divides between Flint residents and the government.

“Levels of trust are already very low when it comes to institutions, state government,” he said. “This only sets us back further in that respect. The idea that these cases would not even go to trial, I think is especially insulting.

“If they had done a fair trial and had all the evidence presented, had there been a verdict that people in the community were not happy with — at least they would have been able to say we had a fighting chance, the evidence was heard, the facts are out. But residents are in a position right now where we aren't even able to see the evidence that was presented to the one-man jury. That's sealed. That's just another way in which this whole process has been extremely disempowering to residents who have been consigned to the sidelines.”

Mays still counts the days since April 25, 2014, when Flint switched its water supply. She said a failure to deliver justice in the Flint water crisis is a sign that another crisis is bound to happen somewhere else.

"If Flint doesn't get fixed properly for the people after all these years, I think today is 3,476 days of media attention and congressional hearings and criminal cases. If we don't get fixed right, their community is not going to get fixed right when it happens to them."

Contact Arpan Lobo: [email protected]. Follow him on X (Twitter) @arpanlobo.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Flint residents malign failure to land convictions for water crisis

Solve the daily Crossword