Leadership in the Oval Office, from FDR to Barack Obama

“CBS This Morning” co-anchor John Dickerson’s essay on presidential leadership is based on a series of Yahoo News interviews with historians. The interviews were conducted by Andrew Romano, Lisa Belkin and Sam Matthews, and the videos were produced by Sam Matthews. The interview with Dickerson was produced by Kristyn Martin.

_____

Presidential leadership has produced as many aphorisms as examples. “Leadership is the ability to get men to do what they don’t want to do and like it,” said Harry Truman. President Coolidge defined the other end of the action spectrum: “Perhaps one of the most important accomplishments of my administration has been minding my own business.” It’s not just presidents who weigh in. Presidential critics have a lot to say about leadership too. It’s what they say a president lacks, when the president doesn’t do what they want him to. In this collection, presidential leadership is defined by men who on at least one occasion focused their energies, and chanced their political fortunes, on something larger than their self-interest. Instead of the easy win, or easy out, they took the long view.

This is usually called “presidential character,” and it was the original conception of the job. The founders believed that the mental and moral makeup of the chief executive would keep the nation in sync with its founding ideals of liberty and equality. A presidential leader had to be “fixed on true principles” as George Washington put it, in order to do the right thing for the country.

These leadership moments meet that original definition, but the office has changed since its launch date. Presidents now campaign for office. Washington and his colleagues didn’t. They thought the low business of grubbing for votes was antithetical to the job. It would lead to presidents who made decisions not by reason, but by what they thought the people wanted.

These stories highlight presidents who faced down political pressure, either by winning over the public or by doing what they thought was right in the face of criticism.

For FDR, leadership meant not resisting the electorate but recognizing that in a large, interconnected nation, only one person could meet the desperate national need. When America’s longest-serving president took office, the unemployment rate was 25 percent, 5,504 banks had closed their doors, and families gathered dandelions for dinner salad. His relationship with the country, built by his innovative communications skills on the radio, allowed him to take enormous risks on behalf of a trusting public. Those risks fundamentally transformed the government into a tool to manage the social impact of the modern age and propelled the presidency toward a celebrity office. The bond between the president and the nation was so profound that the nation grieved as if they had lost a loved one. As Doris Kearns Goodwin put it, “Isn’t it an incredible thing that one man dies and 130 million people feel lonely.”

Though FDR knew how to minister to a needy public, he understood that even with the license to experiment granted during a time of national emergency, a president cannot push the country where it does not want to go. “I can’t go any faster than the people will let me,” he said. Move too fast and the people will not only revolt, but they’ll vote you out of office. So a successful president must know how to lead the public only as far as it is willing to go, without inciting revolt.

Truman and LBJ each pushed beyond the political status quo to advance civil rights for African-Americans. Controversial at the time, both were nevertheless being consistent with America’s founding concern for equality. When Truman desegregated the military, it was “not clear that Truman understood his actions would work out for him,” says Cornelius Bynum. That’s what makes it such a courageous decision. “The idea here is that he didn’t know, but what he did know is that the idea of segregation in the military didn’t sit well with him.”

Johnson, like Jimmy Carter, did not win office as a civil rights crusader. Both built their early careers using implicit or explicit appeals to white identity. Carter changed his tune almost immediately after taking office as governor of Georgia. Johnson evolved in office, becoming what Jonathan Darman calls “the most significant president for the cause of racial justice.” After the brutalization of peaceful marchers in Selma, Alabama, in 1965, Johnson, energized by the heroism of Martin Luther King Jr. and his fellow civil-rights activists, seized on the moment to push the Voting Rights Act, applying his legislative skills to persuade his former colleagues in the Senate. When his aides explained how difficult it would be, Johnson replied, “Well, what the hell is the presidency for?”

Before he became known for leading America into war in Iraq, George W. Bush faced the formidable job of rallying the nation after 9/11. Recognizing the “blood lust,” as he called it, in some of the responses, he faced down anti-Muslim bigotry to uphold civil rights, and the First Amendment, for all Americans.

Bill Clinton pushed for an assault weapons ban using a modern spin on Johnson’s legislative approach. By wrapping his desire for a ban on rapid-fire rifles into a bill that also provided support for law enforcement and a crackdown on crime, he built a coalition from the left and the right to win passage.

George H.W. Bush and Gerald Ford faced the most direct political consequences of the leadership choices they made. Ford’s pardoning of Nixon tanked his approval ratings. Voters thought letting Nixon off the hook was a mere continuation of the trickery of his predecessor. The unelected president thought only through a pardon could he help the nation heal. Ford was not rewarded for the move. His presidency, which had begun with such promise, would never really recover.

For Bush, the decision to break his “no new taxes” pledge affirmed everything his conservative critics had feared about him. Though the 41st president knew raising taxes would weaken support in his own party, he believed strengthening the long-term fiscal health of the country through a budget deal with Democrats was more important. Ultimately, the apostasy would win him a primary challenge and depress the turnout of the GOP base, which contributed to his loss to Bill Clinton in 1992.

In foreign policy, presidents have more room to act than with domestic issues, but dashing risk-taking has enormous downsides. Had Barack Obama failed when he ordered the raid to kill or capture Osama bin Laden, he would have seriously wounded his presidency, roiled relations with nuclear-armed Pakistan and weakened America in the eyes of the world.

The daring success of the bin Laden raid can leave the wrong impression about presidential leadership on foreign policy, however. It is usually through vision and persistence that presidents achieve greatness on the global stage.

Nixon had his eye on transforming the U.S. relationship with China in the mid ’60s, when he was a political outcast traveling to Asia as a private citizen. Once in office, he patiently and secretly re-engaged with a country the U.S. had been shut off from for a generation. When he landed in China in 1972 and met Zhou Enlai, the Chinese premier responded, “Your handshake came over the vastest ocean in the world.”

Jimmy Carter lacked domestic political skills to whip Washington into shape, but he knew how to use his human skills to bring Menachem Begin to an agreement after the Israeli leader was ready to bolt from talks with his Egyptian counterpart Anwar Sadat. Carter also knew that when the deal fell apart, it was worth risking a trip to the Middle East to do the repair work himself. The treaty between the former adversaries has held for forty years amid historic turmoil in the region.

Ronald Reagan, like Nixon, showed leadership by playing against his political type. Both were known as staunch anti-communists. Like Nixon in his outreach to the Chinese communists, the 40th president trusted the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, risking a backlash from his own party to negotiate a mutual reduction in nuclear weapons.

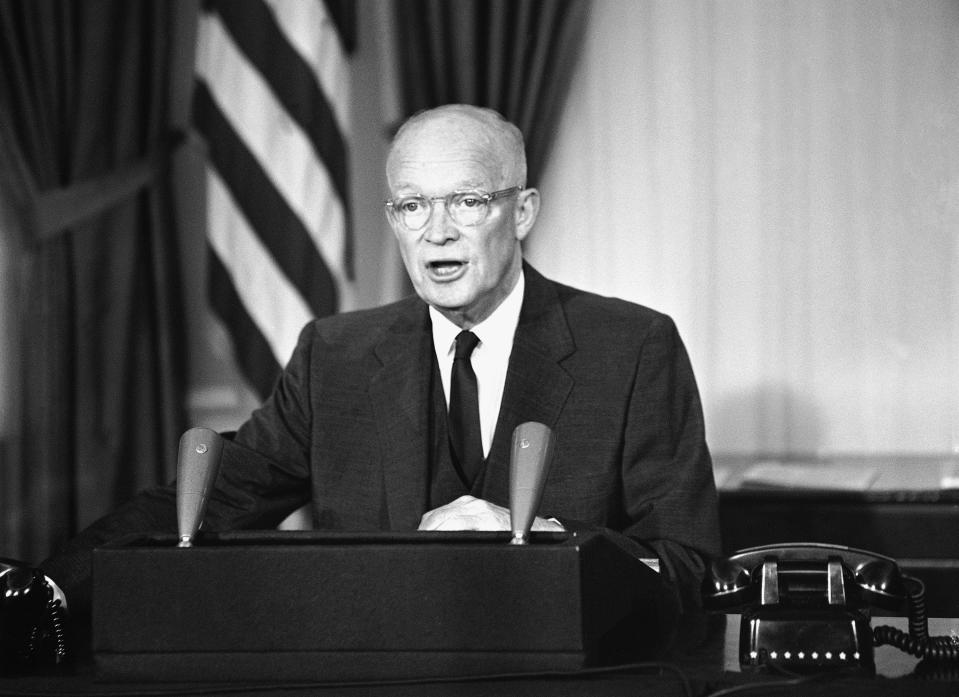

Presidents campaign on grandiose promises, raising expectations of what can be done in an office that was designed to limit its occupant. “I alone can fix it,” promised candidate Donald Trump. But presidential leadership can also be defined by doing nothing. Eisenhower resisted his generals and the “military industrial complex” that encouraged defense spending and foreign adventurism. “Some of the greatest strength is restraint,” says Evan Thomas. “It’s by not doing. It’s by not showing off. It’s by not waving your arms. It’s by not blustering.”

The same was true of John Kennedy, who went eyeball to eyeball with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev over missiles in Cuba. Though he was being pushed to take more bellicose action by his military leaders, Kennedy knew that a mistake or a misinterpretation could be catastrophic. “Kennedy understood very clearly that if he made the wrong move the result could be nuclear war,” says Michael Dobbs.

We study presidential leadership moments because, despite the framers’ intent, the president is now the center of American political life. The fact that presidents of the past were able to overcome the challenges of their times offers hope that the presidents of today can do the same. This is particularly true in an age of heightened partisanship. Great moments of presidential leadership don’t stand the test of time and invite our attention because they are high-scoring events for the chief executive’s home team. They are moments that last because they have benefited all Americans and shaped the world. Presidents and political parties seeking a road to greatness should remember this, and lift their aspirations from Twitter likes and retweets and toward enduring achievements.

_____

John Dickerson has covered American politics since the 1990s. He is a former White House correspondent for Time and political director of CBS News, and he is currently co-anchor of “CBS This Morning” and a contributing editor to the Atlantic. He is the author of “Whistlestop: My Favorite Stories from Presidential Campaign History.”

_____

Click below to view the rest of the 13-part series.

Cover thumbnail photo: The last thirteen U.S. presidents. (Photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: From top left: Getty Images, AP (4), Getty Images, AP (4), Getty Images (2), AP)