Measles outbreak: How Rockland County became ground zero – then hit the 'third rails' with emergency declaration

WHITE PLAINS, N.Y. – Ed Day stood at the podium in the standing-room-only media room and touched three third rails of political discourse, raising calls of anti-Semitism, howls from anti-vaccination groups and pushback from civil libertarians.

The Rockland County Executive declared a state of emergency on Tuesday in Rockland's six-month-long measles outbreak, barring unvaccinated youngsters under 18 from public places for 30 days. Public places include schools, places of worship, shopping centers and restaurants. Parks and outdoor areas are not included.

Those with medical exemptions are not included in the ban.

The declaration, put in force at the stroke of midnight March 27, quickly became an international story, sparking a debate that blends religion, public health and government action.

Day said he saw the declaration as the only tool he had to reverse the measles outbreak’s troubling trajectory, one that could ratchet up considerably with the upcoming Passover and Easter holidays.

Measles, mumps and rubella to massive media response

In pushing parents to have their children get the MMR vaccine to combat measles, mumps and rubella – and holding them accountable if they don’t – Day succeeded in achieving a different sort of MMR: massive media response.

Since issuing the order, Day has been interviewed by TV crews, radio networks and newspapers from around the globe. At a second press conference Friday with County Health Commissioner Dr. Patricia Schnabel Ruppert, one of the questions was asked by a journalist watching on Facebook from Italy.

'Extraordinary outbreak': 5 states fight measles as N.Y. county bans unvaxxed minors in public

As he prepared to declare the emergency, Day said he knew he was about to do something risky.

He would soon learn how risky it was, drawing "vile, disgusting" comments from critics in the anti-vaccine movement.

Whether that risk will deliver the reward Day sought – stemming the measles tide – is an open question and one that could be answered in the weeks following Passover, which begins April 19 and ends April 27.

A highly contagious virus

According to the Centers for Disease and Prevention, "measles is a highly contagious virus that lives in the nose and throat mucus of an infected person."

The virus can spread through the air or through contact with surfaces touched by those who are infected. It can live for up to two hours in airspace where the infected person coughed or sneezed and on surfaces they touched.

Back from near extinction: Anti-vaxxers open door for measles, mumps, other old-time diseases

The virus is so contagious, the CDC says, that "if one person has it, up to 90 percent of the people close to that person who are not immune will also become infected."

A 'moderate' state of emergency

Critics have called the emergency declaration draconian. Day continued to call it "moderate."

"Draconian would have been banning everybody," he said. "Draconian would have been quarantining people. We're not doing that."

Others wondered how it could possibly be carried out. Would people be arrested?

Day said he had spoken with Acting District Attorney Kevin Gilleece.

"He said he would take a moderate approach to this," Day said. "This effort is not meant to act upon what we're allowed to do legally, which is arrest people. We're not looking to do that. This is really educational at this point. But with a firm stroke of the pen doing something that has never been done."

The order holds parents, not children, accountable. Violating the order – bringing an unvaccinated child into a public place – is a misdemeanor, punishable by six months in jail and/or a $500 penalty.

What you need to know: Latest news on the measles outbreak affecting over 150 in New York county

The county executive bristles at the suggestion that the order is a sort of sledgehammer public-service announcement, that it has the force of law, but not the will of law enforcement to carry it out, that it doesn't have teeth.

"The teeth are there, we're not biting," he said. "We're showing you the teeth. We don't want to have the bite anybody. We just want you to obey the law."

The law, he said, requires that people immunize their children when they enter school. The problem, he said, is that some districts have been “loosey-goosey,” permitting exemptions for people who choose not to immunize for reasons other than medical or religious.

'An attention-grabber'

Within minutes of announcing the state of emergency, the story went viral, drawing social-media commenters from far and wide who did not skimp on the vitriol.

They invoked imagery of storm troopers, of people being asked to show their papers, of forced immunizations. The county executive, they said, was going to quarantine Rockland's Orthodox Jewish community, where the outbreak had begun last fall.

That sort of misinterpretation, Day said, was the risk.

More: Facts alone don't sway anti-vaxxers. So what does?

But Day said the reward was in raising awareness using the only tool he felt he had to prevent another spike in the outbreak that is now the largest in the U.S. since the disease was eradicated in 2000.

"It's my judgment, at this point, that we needed to do something to be more supportive of the health department and do it in its most moderate way possible," Day said. "It's an attention-grabber. There's no question about it. And that's what we're doing."

Why now?

For six months, Rockland has battled a stubborn measles outbreak that has shown no sign of abating. Since September, 157 measles cases (and counting) have been confirmed in the county of more than 325,000.

Four new cases were confirmed since the ban went into effect. Day said the "trajectory" of the outbreak prompted him to act.

In September, during the Jewish High Holy Days of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, seven international travelers with the measles sparked the outbreak in the close-knit and insular Orthodox Jewish and Hasidic community of New Square, where large, extended families share homes and houses of worship in close proximity.

There have been smaller measles outbreaks in Orthodox Jewish communities in Ocean and Passaic counties in New Jersey, and in Brooklyn.

Science behind vaccines: Large study adds to proof that measles vaccine doesn’t cause autism

Throughout the outbreak, Day and his health department have met with rabbis and elected leaders in the Orthodox and Hasidic communities, urging them to have their followers vaccinated. The morning of the announcement, Day huddled again with leaders in the Orthodox community.

Day called their cooperation "meritorious," and pointed to the 17,400 MMR vaccines administered since October, most of them in the affected community, at Refuah Health Center in Spring Valley.

In the first two days of the emergency order, 500 vaccines were given, Ruppert reported.

Dr. William Greenberg, a pediatrician and medical director of Jawonio in New City – a regional center catering to the needs of children, adults, and families with intellectual and developmental disabilities and chronic medical needs – praised Day's declaration.

"Contrary to popular nostalgia, measles may be more than a childhood nuisance," Greenberg said. "It carries a risk of greater morbidity and mortality. This is especially concerning among children with chronic disabilities. The medical community, as well as all public officials, must speak with one voice free of dogma and agenda to assure that our most vulnerable citizens are fully instructed against preventable diseases."

Marcia Isaacson, 89, of New City doesn’t need the county executive or a doctor to tell her to take measles seriously. She has lived it.

"Most people’s attitude is something like ‘Oh, it’s something kids get,’ but measles is very serious," Isaacson said. "I was 14 in the Bronx when I got it, Easter Week. It was my birthday and I had a 106-degree fever. It is not to be taken lightly."

'Another petri dish'

Day said he timed his order to precede the upcoming Passover and Easter holidays, the next time family and friends are likely to travel between here and Israel. If the community is vaccinated, he said, even with just the first of the two required doses of MMR, the county will be protected.

"It will be less likely we'll have a repeat performance of last fall. We don't want to have a situation where we create another petri dish. That's what we had last time. It was an unfortunate confluence of events that occurred, seven unvaccinated people who were infected came here."

'God knows how I'm still alive': Son defies mom, chooses to get vaccinated at 18

Day said the Jewish religion's position on vaccination is settled.

The nonprofit Jewish Federation and Foundation of Rockland County took to Facebook to back Day's declaration.

"There is no reason not to get vaccinated. (Except for certain medical conditions.)," the Federation's post read. "There is extensive rabbinical support for vaccination. Federation supports the county's health officials in addressing the situation."

The post also noted: "Sadly some are using the emergency declaration as an excuse for their bigotry. Rockland needs to be united in addressing a very real health crisis and in keeping this among the healthiest and best places to live."

The 1,600 comments on the Federation's post became overwhelming, prompting them to shut down the comments function.

'Over-the-top overreach'

Day knew there would be opposition, but he feared something worse, in a county where friction between the insular Orthodox Jewish community and the rest of the county is always a consideration.

"Knowing the background and how difficult it is to try to keep things calm, one would think this is going to drive them over the top," he said.

What he could not have anticipated was how the story played out in social-media comments, and how one of those third-rail conversations cast a shadow over another.

The order, he said, could have sparked a spike in anti-Semitic rhetoric.

"In a very strange way the anti-vaxxers helped that not to happen," he said. "Because the anti-vaxxers became the focal point, not the religious community. All the conversation has been about the anti-vaxxers back and forth with people here. Most of the anti-vaxxers are not from Rockland County. There's a back and forth between people here in Rockland, who by and large support what I'm trying to do, and those who don't, from elsewhere."

It became a different "us" versus a different "them."

"In kind of a strange way, the good Lord works in mysterious ways," said Day, a Roman Catholic.

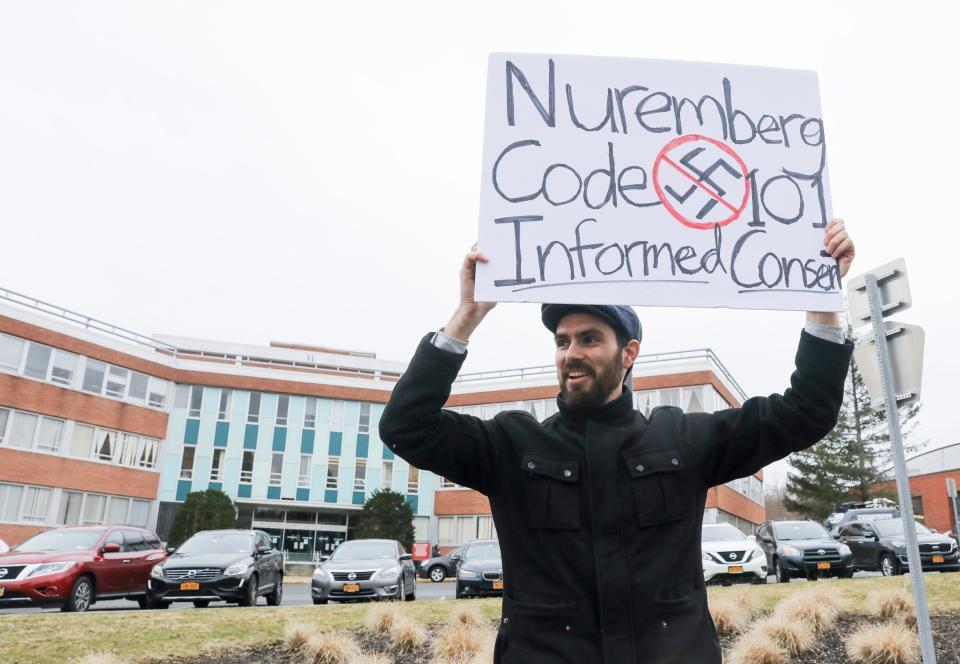

Day and his order have been excoriated by members of the anti-vaccine community, a handful of whom held a tiny, short-lived protest at the Palisades Center, one of the public places affected by the ban. They did not bring children.

"This is an over-the-top overreach," said Rita Palma of Bayport, Long Island, a lobbyist who founded an organization called "My Kids, My Choice" and wore a T-shirt that read #vaxwoke and #mychoice. She was among the 10 protesters who gathered near the mall's carousel.

The pugnacious 67-year-old county executive has pushed back, calling Facebook comments from anti-vaccination advocates "vile and disgusting." Some compared his order to the actions of Adolf Hitler.

"That language – the Hitler stuff – that was from anti-vaxxers. That wasn’t from the Orthodox community," Day said.

Schools and shots

Day’s order bars unvaccinated students from attending school unless they have a medical exemption.

On the first day of the ban, BOCES communications director Scott Salotto reported that each of Rockland’s public school districts saw a range of 11 to 50 children missing classes as a result of the ban.

More: Judge in New York denies request to allow 44 unvaccinated students back in class

Day on Thursday said he had asked his health department to “drill down” to find out how soon a newly vaccinated student could return to class.

‘We’ve heard four (days), we’ve heard 21, we’ve heard 30,” Day said. “I said, ‘We need an answer here because we have people in school.' If they can go to the school the next day, we’d rather have that. Let them go to the doctors, get the shot and go to school. And they can. The next day.”

But the CDC disagrees.

On Friday, Benjamin Hayes, a senior press officer with the CDC’s Infectious Disease Media Team, was asked how long a student would have to wait before going back to school.

“It takes three weeks for the shot to become effective,” he said.

A right to protection

"I expected some frustration on the part of families," Day said. "Nobody likes to be told what to do. I get that."

But Day says inaction is not an option.

“I'm not going to wait to see somebody get sick or die or get complications to figure out what's going to happen,” Day said. “If I have infected people going to stores in the Palisades Center mall or other parts of the county, they are exposing other people.”

“We have babies out there, my grandson," he said. "We have pregnant women out there. We have people who are autoimmune, cancer patients. They have a right to be able to go around where they go and be protected against a basic disease that was eradicated 19 years ago."

Contributing: Rochel Leah Goldblatt, Steve Lieberman, Robert Brum, Aisha Powell

This article originally appeared on Rockland/Westchester Journal News: Measles outbreak: How Rockland County became ground zero – then hit the 'third rails' with emergency declaration