Michigan Democrats were burned in 2016. Here's how they're trying to defeat Donald Trump in 2024.

WASHINGTON – Former President Donald Trump won the state of Michigan in the 2016 presidential election by just 10,704 votes.

It was an exceedingly small number in a state with around 7.7 million voting-age adults. And for Michigan Democrats, the tight loss was a crushing blow.

Sen. Debbie Stabenow, the senior senator from Michigan, felt she had choice: Wallow in her misery or go in and reorganize the state's Democratic Party.

She made a call to Harry Reid, then the Senate Democratic Leader from Nevada. His state's party had a year-round campaign operation where they were communicating with voters even in non-election years. Stabenow liked the idea.

It was the start of the Michigan Democratic Party’s effort to transform from a shoestring operation, dependent on the national party, to a perennial organizing force. And their fortunes have changed in the elections since.

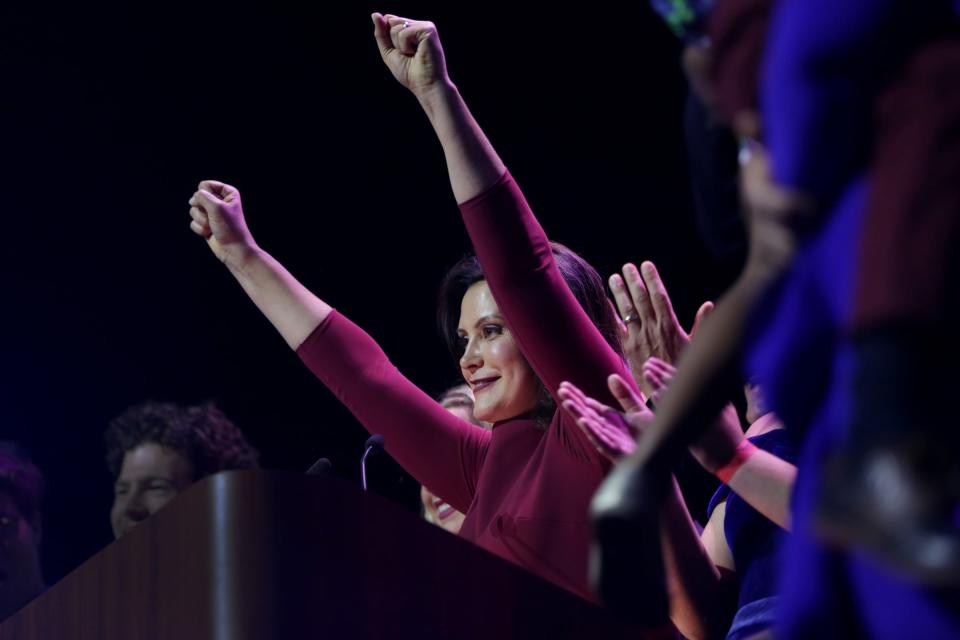

In 2018, Democrats swept the state’s highest offices. Voters elected Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson and Attorney General Dana Nessel. They also approved a series of ballot initiatives favored by Democrats – legalizing recreational marijuana use, expanding voting access efforts and creating a new redistricting process.

Biden flipped the state in 2020. And in 2022, the party took control of the state's House and Senate for the first time in 40 years, bucking predictions of a “red wave.”

Their ascent came at the same time the Michigan Republican Party – once known for tightly organized campaigns – appears to have spun into chaos. Two different leaders claim to be the rightful party chair with plans to hold dueling nominating conventions this weekend.

Observers acknowledge there are many factors that went into Democratic victories in the state in recent years. But they say the party’s transformation after the 2016 election laid the groundwork.

“A strong state party provides the infrastructure, the road that candidates put their cars on,” said Michigan Democratic Party Chair Lavora Barnes.

“If that road is bumpy or broken or dysfunctional, it makes it harder for the campaigns to run the kinds of campaigns they want to run to win.”

However, even as Democrats in the Wolverine State gear up for a tight election this fall, it's not clear their statewide organization will save them from being burned again.

Trump leads President Joe Biden in multiple hypothetical matchups in the pivotal swing state. And Biden faces dissension within his own party over his steadfast support for Israel in its war against Hamas. The conflict has killed more than 29,000 Palestinian civilians and personally impacted many in the state's large Arab-American population.

'We're not going to let this happen to us again'

In the lead up to the 2016 presidential election, the Michigan Democratic Party knew the election was going to be tight. They urged Hillary Clinton’s Brooklyn-based campaign to send more organizers and resources to the state, but their calls fell upon deaf ears.

Their get-out-the-vote effort began in earnest in the late summer of 2016, only months before the election. Guided by polling showing the state as a safe win, the Clinton campaign dismissed many in-person opportunities to reach undecided voters.

As Stabenow began searching for a solution, leaders in the state party were doing their own introspection.

They had had inklings the defeat was coming, but it still hurt. If they had a stronger organizing and field program, said Brandon Dillon, then-chair of the Michigan Democratic Party, “we probably could have found those 11,000 votes.”

“We had to wait for the national campaign to show up – and they showed up late,” said Barnes. “We woke up the next week and decided that we’re not going to let this happen to us again.”

How did Democrats mobilize in Michigan?

With little cash to work with after the bruising 2016 cycle, Michigan's Democratic Party decided not to fill positions in their headquarters in favor of hiring field organizers. Those organizers threw house parties to pay for part of their salaries.

By April 2017, they were knocking on doors. The idea was to have conversations with voters well before the 2018 midterm elections and get a sense of what they cared about without asking – yet – for their vote.

They gathered the chairs of county parties and asked them to do anything that would get local Democrats more involved. And they tried to harness the new energy coming from Democrats after Trump’s victory: Hundreds of people had signed up to be party members even without solicitation, Dillon recalled.

Stabenow, who was up for reelection in 2018, pumped $150,000 from her campaign into the off-season door knocking efforts. And she asked area party leaders to go a step further – use the information they’d gathered from voters in the off-season to campaign for the whole Democratic ticket, from governor to university school boards.

Stabenow and former Rep. Brenda Lawrence, D-Mich., kicked off the new “One Campaign” in June 2018, handing out flyers with photos of every Democratic candidate's face. They began (and have begun ever since) in Detroit, as a symbol of their commitment to the state’s Black communities, which have a decades-long history of feeling taken for granted by the Democratic Party.

And now preparing to retire from Congress at the end of the year, Stabenow has also put nearly $500,000 from her campaign funds into a new messaging effort, including pushes to counter Trump.

Strengthening their statewide presence has paid off, said Adrian Hemond, a Democrat and CEO of Grassroots Midwest, a bipartisan consulting firm, especially in winning more votes in rural and suburban areas.

“That makes a huge difference come election time. And it’s also harder to execute on that just in an election year,” he said. “That’s not a six-month job. That’s a year-and-a-half job.”

Division in the Michigan GOP

As the state Democratic Party’s strategy shifted after the 2016 election, so did their opponents.

Trump acolytes rose in the ranks as more moderate, traditional Republicans increasingly appeared to lose power in the state. In 2023, the party elected Kristina Karamo as chair, a vocal proponent of unsubstantiated claims that the 2020 election was stolen.

Earlier this year, a group of Michigan Republicans voted to unseat Karamo and elected former U.S. Rep. Pete Hoekstra as their new chair. But Karamo claims the vote was illegitimate and says she is still in charge, despite the Republican National Committee dubbing Hoekstra the rightful leader.

The uncertainty and allegations of financial mismanagement under Karamo are alarming national Republican strategists. They say the work of state parties can make a big difference in places like Michigan, where elections can be won by just a percentage point or two.

Both the Hoekstra- and Karamo-led wings of the Michigan Republican Party did not respond to interview requests for this story.

“The party is beyond disarray. They have imploded and there is no (organizing) effort,” said John Truscott, CEO of consulting firm Truscott Rossman and former communications director for GOP Gov. John Engler. “They have no money, no people, no staff, nothing.”

In the party’s absence, the state legislature’s GOP committees have been fundraising for conservative candidates while Trump and other presidential candidates attempt to backfill party coffers. There are hopes that Hoekstra can revive the party’s once-formidable organizing effort, but the clock is ticking.

“There’s absolutely no question that the Republican Party is really behind and stands almost no chance at catching up on the state level to what the Dems are doing,” said John Sellek, CEO of Harbor Strategic Public Affairs and former communications director to GOP Attorney General Bill Schuette

However, it's not clear the state's Republicans will need to build up the same muscle to convince GOP voters to head to the ballot box in November. Democrats have a “huge advantage” Sellek explained, “but I think they know they’re gonna need it – because every single poll shows the energy is behind Trump.”

Joe Biden struggles with voters on age ?and Gaza

Two recent polls show Trump leading Biden in Michigan – one by 4 percentage points and another by 8.

Support for Biden appears to be slipping in part because of his age. At 81, he is the oldest president in U.S. history.

A recent report from special counsel Robert Hur, who served in Trump’s administration, portrayed him as an elderly man with potential memory issues, an allegation that didn't comfort voters who have long been concerned about the president's age.

Biden’s refusal to demand Israel stop its devastating counterattacks in Gaza may mark another vulnerability this fall. Michigan is home to the second-largest population of Arab Americans in the U.S., many of whom have lost loved ones as Israel’s bombardment of the strip continues. Young people – another core Democratic voting bloc – also overwhelmingly oppose Biden’s handling of the conflict.

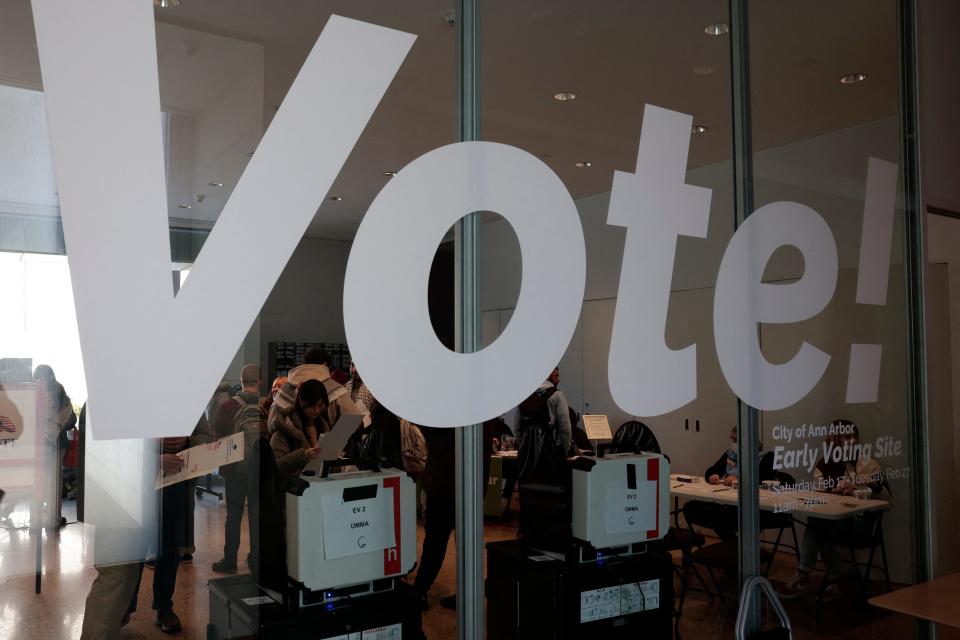

Some progressive Michigan Democrats are urging voters to vote “uncommitted” in Tuesday’s primary election to show Biden he could be in trouble if he continues to ignore demands for a cease-fire.

Former Rep. Andy Levin, D-Mich., has been one of those advocates. He said he does not want Trump to be elected, but he argued that Biden can’t win Michigan unless he changes course on Gaza.

“The anger is real,” he told USA TODAY. “I think it would be much more dangerous for Joe Biden if this Listen to Michigan campaign had not developed. Why? Because he wouldn’t have gotten any message.”

Other Michigan Democrats who spoke with USA TODAY emphasized the importance of listening to voters’ concerns, but they remained confident in Biden’s ability to lead and win in the fall.

It's not clear that confidence echoes among voters across the state, but party organizers have laid out a clear game plan. They're trying to make a case for Biden by drawing attention to his accomplishments, such as massive investments in climate technology and infrastructure, and by arguing another Trump presidency could endanger democracy, reproductive rights and the economy.

“President Biden may be 81. But think 91 when you think of Donald Trump – 91 felony indictments,” Stabenow said, referencing the four criminal cases pending against the former president. “To me, it’s pretty clear.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How Michigan Democrats are trying to defeat Donald Trump in 2024