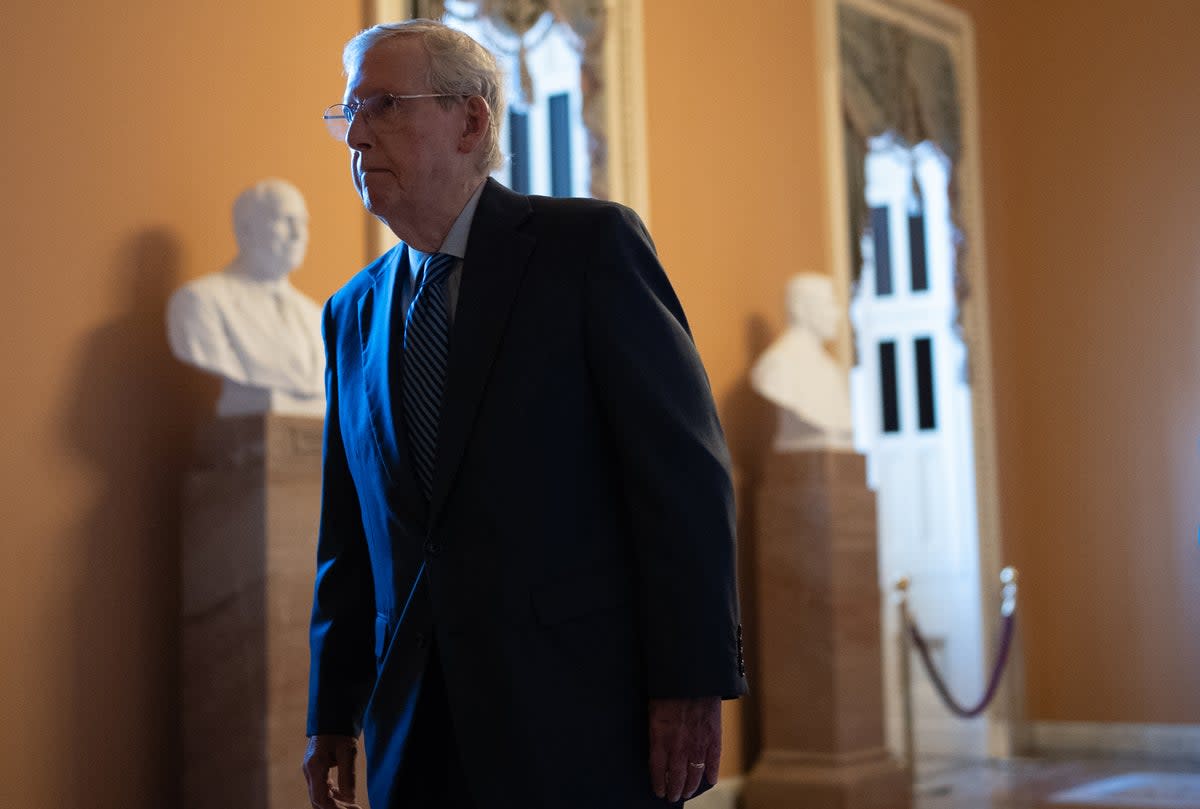

Mitch McConnell takes his parting shot at Tucker Carlson — but avoids Trump

Perhaps the ultimate totem of Senate Minority Mitch McConnell’s power is that nobody forces him to speak. Where reporters stick their arms out to grab quotes from his fellow Republicans or his gabby Democratic counterpart Chuck Schumer, the same can’t be said for when McConnell takes the handful of steps from his office off the Senate floor to speak in the chamber. Most of the time, journalists don’t bother him at all — they know better.

When he does speak, the mercurial Kentuckian rarely emotes and only gives the bare minimum in terms of information. That’s made McConnell’s remarks both on the Senate floor and during a press conference on Tuesday afternoon so surprising.

On Tuesday, the Senate teed up what McConnell hopes to be his defining legacy item before he steps aside as Republican leader later this year: aid to Ukraine as it seeks to push back against Vladimir Putin’s assault. After nearly six months of opposition, largely from his own party, to assisting Ukraine, the bill was finally advanced. And McConnell did not mince words when asked why it took so long for Republicans to get behind it.

“I think the demonization of Ukraine began by Tucker Carlson, who in my opinion ended up where he should've been all along, which is interviewing Vladimir Putin,” McConnell said. “And so he had an enormous audience, which convinced rank-and-file Republicans that maybe this was a mistake.”

The words were a shock for many. Former speaker John Boehner — whom nine years ago said “enough” after dealing with GOP extremists — once said McConnell “holds his feelings, thoughts, and emotions in a lockbox closed so tightly that whenever one of them seeps out, bystanders are struck silent.”

McConnell’s not entirely wrong. Carlson — the former Fox News provocateur who now hosts a show on Twitter/X where he did interview the Russian president, some might say with kid gloves — has routinely spoken out against the idea of the US supporting Ukraine. When Ron DeSantis called the war in Ukraine a “territorial dispute,” he did so in response to a questionnaire from Carlson.

But the hostility to Ukraine also runs much deeper than the words of a gadfly like Carlson. Many other conservative consiglieres — such as Steve Bannon, aide to former president Donald Trump — have expressed similar sentiments, preferring instead to posture about “America First”.

Indeed, it was Republican revulsion at supprorting Ukraine that prompted McConnell to dispatch conservative Senator James Lankford of Oklahoma to negotiate with Democrats over an aid bill in the first place. Lankford was able to negotiate tightened restrictions on immigration and more security provisions at the US-Mexico border — before Trump ultimately killed the bill off entirely.

But McConnell has tried to avoid speaking Trump’s name ever since the former president incited a riot at the Capitol that threatened his life. As a result, he discussed the contours of those negotiations while dancing around the former president.

“I think the former president had sort of mixed views on it,” he told reporters. “We all felt the border is a complete disaster, myself included.”

While McConnell would like to see himself as a vanguard of protecting democracy abroad, the last six months have revealed how little power he has left. Once, he had an iron grip on the Senate Republican conference that allowed him to block Barack Obama’s agenda and rapidly confirm Trump’s judges — a move that ultimately led to the death of Roe v Wade.

But on Tuesday, he found himself in the same position that House Speaker Mike Johnson has recently: relying on Democrats to pass aid to Ukraine. While 30 Senate Republicans voted to allow for cloture compared to a minority of Republicans in the House, he still had to grapple with the fact that he no longer represents a party that champions a robust prohibitive foreign policy.

McConnell also criticised those in his party who did not want to support Ukraine, including some of the candidates whom he hopes will hand the Senate to the Republican Party when he steps aside later this year.

“I think we’ve turned the corner on the isolationist movement,” he told reporters. “I’ve noticed how uncomfortable proponents of that are, when you call them isolationists.”

But the fact remains that the isolationist wing of the GOP will most likely continue to grow. And any of McConnell’s potential successors will not have the skill, the tools or the gravitas to temper that wing as well as McConnell. Should Trump re-assume the Oval Office, those isolationists will have a powerful ally in the White House who can negate even would-be McConnells.

Indeed, the Democrats now see themselves as more willing to use American might to defend its values abroad than Republicans (albeit Democrats’ divide on Israel shows they debate when and where to use it).

As I’ve said before and will repeat perpetually, the isolationist and Trump wing of the GOP would not be as strong had McConnell not accommodated Trump at every step of the way. Liberals will likely say it will be his decision to acquit Trump after January 6 despite his open disdain for the former president that is his biggest legacy, rather than aid to Ukraine.

But the two are in fact intertwined. Had McConnell not let Trump off the hook, then Trump would not still be an influential force in the party.