Most US states don't have universal air conditioning in prisons. Climate change, heat waves are making it 'torture'

It was nearly 100 degrees outside in South Texas the day Quintero Jones died. Inside his cinder-block prison cell in the middle of summer, it felt even hotter.

Jones, 37, was asthmatic and had high blood pressure, and like many incarcerated people, he was taking medications that can affect sensitivity to heat.

The day he died in July 2015, Jones was lying on the floor of his cell to "stay away from the baking hot cinder-block walls" when he had an asthma attack exacerbated by the heat, according to a lawsuit filed by his family. His emergency inhaler had been taken earlier that day during a search, and his unit was on lockdown.

“He’s dying!” Jones’ cellmate yelled, while other inmates tried to get the attention of officers, the lawsuit says. It took up to 20 minutes for someone to check on Jones, who was “hunched over” and “gasping for air,” the suit claimed. Staff brought him outside his cell, where he began vomiting and collapsed. Staff performed CPR for 24 minutes before he was transported to a hospital and pronounced dead.

Some things have changed in Texas prisons since Jones’ death. The state has added more than 3,500 air-conditioned beds over the past three to four years, and it has plans to add nearly 6,000 more.

But only about 30% of the roughly 100 prison facilities in Texas are fully air-conditioned, according to a report released in July by the Texas A&M University Hazard Reduction and Recovery Center and Texas Prisons Community Activists.

And Texas is far from alone. At least 44 U.S. states, including those with some of the highest temperatures nationally, don't have universal air conditioning in their prisons, according to a USA TODAY analysis of media reports and information from state corrections departments. The analysis is the most comprehensive data available about cooling systems in U.S. state prisons, as the information isn’t tracked.

SEE A FULL BREAK DOWN: Map shows at least 44 states without full air conditioning in prisons

With scientists and studies chronicling the intense impacts climate change is having in fueling hotter temperatures across the country, advocates for incarcerated people are sounding the alarm about sweltering conditions in U.S. prisons, where current infrastructure is ill-equipped for a problem on track to worsen.

Advocates say the hot conditions in prisons may constitute "cruel and unusual punishment" prohibited by the Eighth Amendment.

David Fathi, the director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project, said people should consider the question of values: "Whether we as society find it acceptable to torture incarcerated people and to expose them to conditions that we know are going to kill at least a few of them and are going to cause serious injury to some additional people."

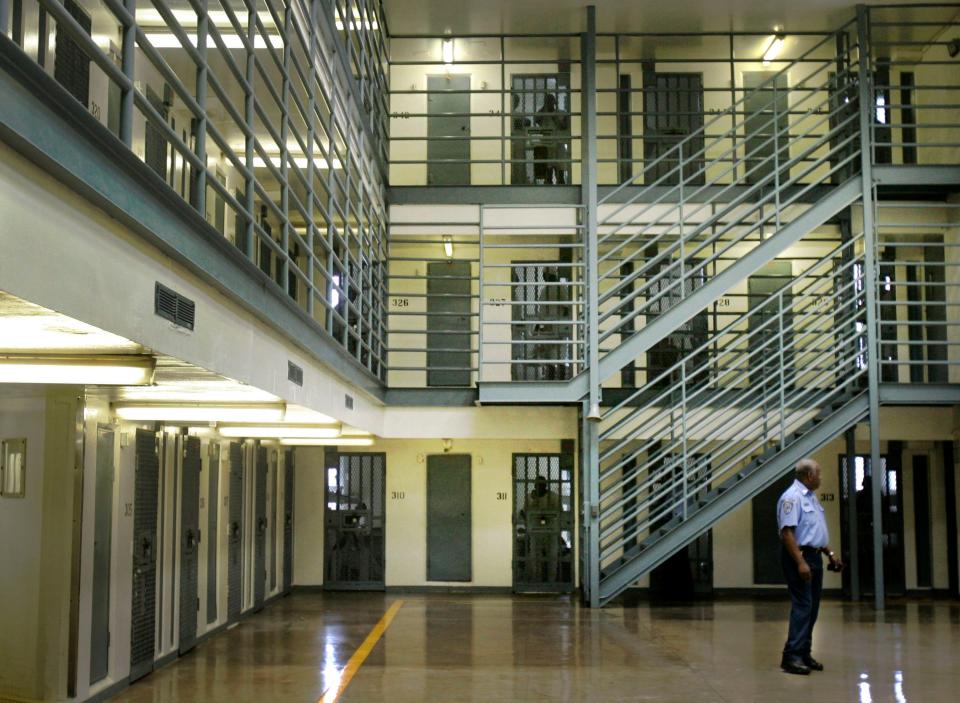

No air conditioning in many US prisons

Only four of Alabama's 26 state correctional facilities have air conditioning in all dormitories, in a state where it regularly reaches the mid-90s outside in the summer, reported the Montgomery Advertiser, part of the USA TODAY Network. And just 24% of hot, humid Florida’s state-run prison housing units are air-conditioned, said Molly Best, a Florida Department of Corrections spokesperson.

USA TODAY reviewed media reports and public information from all 50 states and contacted corrections departments where information was unavailable. The results showed at least 44 states don't universally air condition their prisons.

Only one state – Tennessee – said its prisons were fully air-conditioned. A handful of other states had nearly universal air conditioning or used other cooling methods to control the temperature in all areas of their facilities.

A 2019 review by the nonprofit criminal justice research organization Prison Policy Initiative found prisons in 13 of the country's hottest states – mostly in the South – including Kansas, Louisiana, Virginia and North Carolina, aren't fully air-conditioned. USA TODAY found a slew of other states representing all regions of the country that didn't have full air conditioning in their facilities.

Two states, Alaska and Montana, had no air conditioning in any of their prisons.

"Our climate just really doesn’t call for it," said Betsy Holley, a spokesperson from the Alaska Department of Corrections.

While some states aren't typically known for oppressive heat, experts say they should be prepared for the realities of a changing climate.

“This is going to be an issue in virtually every part of the country,” Fathi said.

SENATE PANEL: Atlanta federal prison 'lacked regard for human life'; weapons, drugs trafficked

In Michigan, the most medically vulnerable and mentally ill prisoners are housed with air conditioning. Other inmates have chilled air, ventilation systems or fans, said Chris Gautz, a spokesperson for the state's corrections department.

"There is no law requiring the department to provide air conditioning for prisoners, just as there is no law requiring members of the public to have air conditioning in their homes," Gautz said.

Climate change set to make prisons even hotter

Climate change is on track to make it unbearably hot in prisons across the country, not just the South, where advocacy efforts have traditionally focused, experts say.

This summer, intense and unexpected heat waves in the Northeast and the Pacific Northwest caused heat-related deaths. Nearly 6,000 high-temperature records were broken this July, and millions of Americans were under excessive-heat warnings from the Southern Plains to New England as heat domes blanketed the country.

REPORT: Climate change is 'first and foremost' a health crisis

A NEW NORMAL: Temperatures in the U.S. could rise 3-12 degrees by the end of the century, and the impact on human life will be brutal.

"When we think about how climate change is going to continue to affect people who are incarcerated, we will also be thinking about the places that haven't historically acclimated to the heat,” said Julie Skarha, a researcher with the Brown University Department of Epidemiology. “They're going to be even more at risk without that infrastructure and the resources."

What happens when temperatures get too high

The summer of 2015, when Jones died, temperatures reached 100 degrees on five days in Beeville, Texas, where he was incarcerated, according to historical weather data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The high was 98 degrees the day Jones died, data shows. This summer, temperatures hit 100 degrees on 15 days there, and most prisoners currently in his former unit still don’t have air-conditioned housing.

The lawsuit brought by Jones' family was settled by officials at the Texas Department of Correctional Justice for at least $80,000, according to federal court records. He was serving a life sentence for capital murder when he died.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice notes that heat exhaustion can be felt beginning at 80 degrees, with the risk for heat stroke beginning at around 91 degrees, according to the Texas A&M study, which found temperatures inside correctional units in the state regularly reach 110 degrees. At least one unit has topped 149 degrees, the study says.

WHAT IS A HEAT WAVE?: Here's what it is, how it affects your body and how to stay safe.

“It’s torture. … The level of the heat inside of these facilities is such that it's difficult to breathe, it's difficult to move,” said Texas state Rep. Terry Canales, a Democrat and longtime advocate for cooling prisons.

Dying from heat is a common fear among inmates, according to the Texas study. The report detailed the impacts of high temperatures and analyzed survey responses from over 300 inmates on their experiences between 2018 and 2020.

“I feel like I’m going to die right here in this cell or have one hell of a heat stroke…They don’t care if I die in here or not,” one survey respondent wrote. Respondents were kept anonymous in the report to protect them from retaliation, said Amite Dominick, who co-authored the report.

New Jersey's corrections watchdog released an oversight report last week, finding temperatures inside cells got as high as 88 degrees in July and hit 94 degrees in August during site visits.

The watchdog office "heard reports of people engaging in assaultive behavior in order to be transferred to air-conditioned disciplinary housing assignments," the report said.

Overcrowding in prisons adds to the problem: more bodies, more heat, said Daniel Holt, a researcher on heat in U.S. jails and prisons.

"The more dense your indoor population is, the more difficult it gets when you have high temperatures, high humidity," he said.

Many prison facilities, particularly older ones, simply weren't built with temperature control and efficiency in mind. Prison administrators are more focused on safety, Holt said: "Climate is just sort of outside their wheelhouse."

'Piecemeal approaches' don't replace AC

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice told USA TODAY in a statement that its policies to help mitigate heat in prisons include increased access to water and ice, fans and cool “respite” areas prisoners can go to.

The department said many of the state's facilities were built before air conditioning was commonly installed, and prisons built in the '80s and '90s didn't have AC because of the cost to install and maintain it. The state has estimated it would cost $1 billion to convert facilities to include air conditioning, and another $140 million each year for maintenance, though some advocates for the incarcerated say those figures are an overestimate.

Amanda Hernandez, a spokesperson for the department, said current measures within prisons are working, citing that there have been no deaths from heat this summer in its facilities. But 12 inmates "required medical care beyond first aid" due to a heat injury this summer as of late August, Hernandez added.

"Each summer, we continue to refine and improve our practices," Hernandez said in the statement. "What has not changed is our commitment to do all that we can to keep staff and inmates safe."

But with more than 100,000 inmates in the Texas prison system and staffing shortages, the strategies are “inefficient and ineffective,” the Texas study authors wrote.

"Their mitigating factors don't work here. They do not have enough employees, first and foremost," Dominick said.

Inmates who responded to the survey reported inconsistent access to water and ice. Sixty-one percent said they didn’t have access to additional cool-down showers. Many reported being denied access to respite areas due to overcrowding or lack of staff, or only being allowed to go once per day for only a few minutes.

"These are just piecemeal approaches," said Jamelia Morgan, a professor at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

'Lethal combination': Heat and disability

Many inmates are at greater risk of heat-related illness because of underlying conditions or medication they take that can affect their body's ability to regulate temperature, making heat in prisons a disability rights issue, said Morgan, who is also board president of the Abolitionist Law Center, which advocates for prisoners' rights.

State prisons are required to abide by the Americans with Disabilities Act, a civil rights law that protects people from being discriminated against based on a disability and offers protections, including the right to reasonable accommodations.

'WE'RE FIGHTING A BEAST': Families accuse private prisons of failing to help dying loved ones

Prisons generally don’t implement accessibility measures, like air conditioning for inmates who are at high risk, unless they are prompted by litigation, Morgan said.

One inmate who was surveyed in the Texas report said he had Type 2 diabetes, asthma and high blood pressure, and described "inhumane living conditions" in non air-conditioned units.

"I shouldn’t even be assigned housing on this row, but they don’t really care about the inmate's health,” said the inmate, who was housed at the Justice William G. McConnell Unit, the same South Texas prison where Jones died in 2015.

WHO LOOKS OUT FOR VULNERABLE AMERICANS?: Climate change is fueling extreme heat. Buddy programs could help disabled, elderly

Fathi, the head of ACLU’s National Prison Project, said the country's problem with mass incarceration and “uniquely long sentences” means the prison population is not only large, but also aging. As people age, they are more vulnerable to heat-related injuries and more likely to have other conditions. It's a "lethal combination," he said.

'Cruel and unusual' punishment?

The Eighth Amendment of the Constitution prohibits cruel and unusual punishment, meaning while prisons don't necessarily have to be comfortable, they do have to be humane, according to Fathi, who has successfully litigated cases on prison conditions in Wisconsin, Mississippi and Arizona.

"We're not talking about some exotic luxury that's enjoyed only by a tiny fraction of the rich," Fathi said. "(Air conditioning) is something that's utterly routine in virtually every kind of building that has people in it, except, for some reason, prisons."

The New Jersey corrections watchdog report said it was the state's responsibility to protect inmates and prison staff from the heat.

"Because people detained in prison facilities cannot leave of their own accord and have limited control over their movement, possessions, and environment, the state assumes a responsibility for their humane treatment, including a responsibility to protect them from potential harms associated with extended exposure to heat and cold," the report said.

Courts are increasingly having to confront heat in prisons as an issue that may violate the Eighth Amendment, Fathi said. The problem with approaching the issue through litigation, though, is cases are brought in the aftermath of an incident and have to prove there was serious risk of injury or death, he said.

“Litigation is reactive," Fathi said. "We don't want it to get to that point. We want to see the necessary health and safety measures to be taken before people get sick and die."

Canales, the Texas state lawmaker, wants the state to be proactive instead. He introduced a bill in the Texas House last year that would have the state spend $100 million every two years over a six-year span to cool the state’s prisons. It was passed in the House, but failed to be taken up by the state Senate. He said he would try again, but has little hope it will be signed by Republican Gov. Greg Abbott.

“Most people, they hear that the jails aren’t air-conditioned and the attitude is, ‘Those are criminals anyway,’” he said, adding that many incarcerated people are in for nonviolent drug offenses. “And this is the treatment they’re getting, and it’s cruel and unusual.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Heat waves impacting prisons without air conditioning across US