Nashville is complicit in country music's diversity problem and leaders need to step up

On the evening of Dec. 31, 215,000 people gathered at Bicentennial Capitol Mall State Park to ring in 2024. The show, dubbed Nashville’s Big Bash, aired on CBS, one of a series of New Year’s celebrations taking place across the country. It was an opportunity to showcase all of Nashville, a city with a diverse population, including a multitude of artists who work in diverse genres.

The show started off well enough. An ode to hip hop’s 50th anniversary featured local emcees Daisha McBride and Tim Gent, as well as newly elected Mayor Freddie O’Connell spinning a DJ set. Nashville has long been a hotbed for pop, R&B, hip hop and other genres, even if their creators have largely been relegated to Music City’s sidelines.

Indeed, when CBS cameras turned on, and Nashville’s Big Bash was broadcast to millions of homes around the country, McBride and Gent were not to be seen.

In their stead were Thomas Rhett, Carly Pearce, and other country artists — the majority of whom were white and, apparently, a more appropriate reflection of Music City.

Another view: How Country Music Association is cementing its future by investing in Black artists

Country music is the calling card of Nashville, but it doesn't represent everyone

For as much as locals lament Nashville’s emphasis on country music, there is no denying that, to people outside the city, Nashville is country. There is no separation between the two, no alternate universe in which New Yorkers or Minnesotans or Kansans don’t think of Nashville and simultaneously conjure images of banjos and acoustics, or the sound of some bro country white guy twanging about his brand-new truck.

This affiliation has, of course, been wonderful for Nashville’s coffers. In 2018, I interviewed Butch Spyridon, former CEO of the Nashville Convention and Visitors Corp, for a profile for another outlet. In discussing Nashville’s burgeoning status as a premier destination, he spoke to the intentionality of the CVC’s efforts — specifically, the need to fully leverage Nashville’s Music City moniker.

“We had country music,” he told me. “We had this great songwriting community, and we had the friendliest people in the country …”

In 2023, just before his retirement, Spyridon told a television reporter that the CVC's wholesale adoption of Music City brand “allowed the plan to open itself up to more genres than just country music.” But by that point, country had long been positioned as Nashville’s key draw and primary industry, what with the Grand Ole Opry and Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, a Broadway full of honky tonks and a downtown takeover by the CMA Fest every summer.

The problem is that, despite the beliefs of industry insiders and out-of-town television network execs — plus the complicity of local leaders — country music doesn’t fully represent this town. It never has, and it certainly doesn’t now.

Tracy Chapman made history at the CMAs, but Black female artists and songwriters are severely underrepresented

When Tracy Chapman became the first Black woman with a No. 1 on the Billboard Country Airplay chart as a solo songwriter for “Fast Car” sung by Luke Combs — and, later, the first Black woman to win a Country Music Academy (CMA) Award in any category — the country rejoiced. And country music basked in the praise.

But when Tracy Chapman’s song debuted 35 years ago, it was never considered a country song, and she was never acknowledged by the country music industry. She didn’t come to Nashville, sign a publishing deal, get invited to a songwriting session with a couple of other writers and then decide to record it herself instead of trying to get it cut by another artist.

Chapman is an anomaly. And based on industry history — including its most recent — any Black songwriter hoping to replicate her CMA success over the next 57 years (the Awards were first handed out in 1967) has no real path to follow. To add to her firsts: Chapman is the only Black songwriter of any gender to win CMA Song of the Year.

Black songwriters are a rarity on publishing rosters, especially if they’re not also artists, and even more so if they’re also women. This discrepancy is significant for Black writers who hope to have a song cut by signed artist, let alone achieve a No. 1, like Chapman. As Warner Records artist and songwriter Brandy Clark told Billboard in 2021, “I write with who my publisher puts on my book to write with.”

As such, Chapman’s recognition by the CMA is no more indicative of the current state of country music than a 65-degree day in January is a sign that winter is officially over — or, more fittingly, that Lainey Wilson’s 2023 successes are proof that the country music industry has reached a state of gender equity.

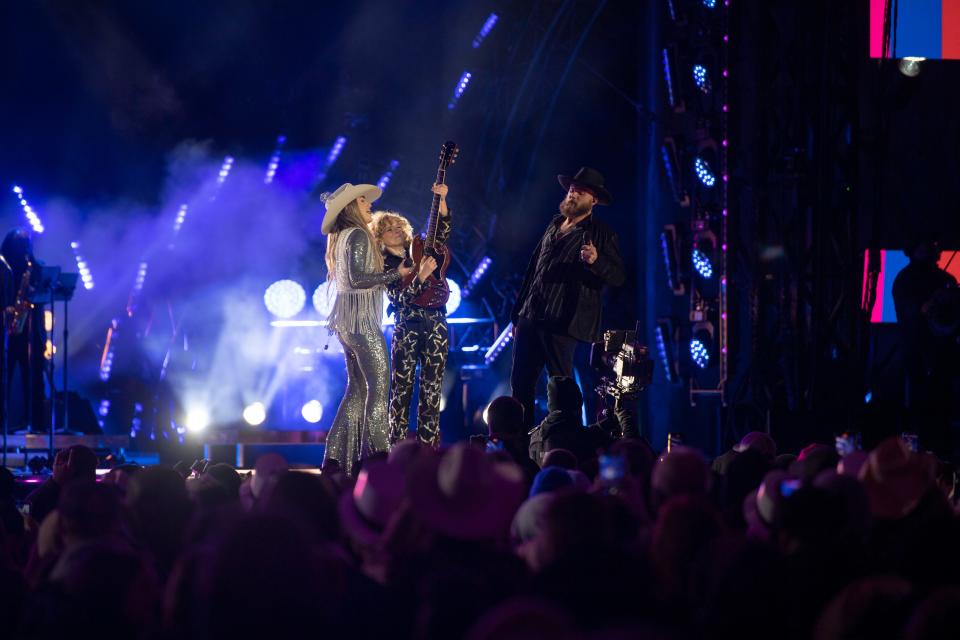

Wilson, who enjoyed a coveted main-stage spot during Sunday night’s New Year’s Eve broadcast, logged three No. 1 hits on Billboard’s US Country Airplay chart last year. But she was the only solo female act to claim a No. 1 in both 2023 and 2022. (Kane Brown’s wife, Katelyn, scored a chart-topper last year with “Thank God,” a duet with Brown.) For five weeks in 2023, Wilson was also the only woman in the Top 20.

While terrestrial radio’s impact and influence continues to drop in other genres, it still reigns supreme in country, where it determines eligibility for some Academy of Country Music (ACM) and CMA awards, as well as a not insignificant percentage of songwriter and artist income. Yet women continue to lag far behind men in radio spins. Separate white women (who still enjoy a measure of privilege in the industry, particularly outside of radio), and the data is even more damning.

Dr. Jada Watson, assistant professor at the University of Ottawa and creator of the "Redlining in Country Music" study, notes that representation for all Black artists on country radio has actually declined since 2019 — this, despite the so-called racial reckoning of 2020.

In 2023, Black women received only 0.02% of all airplay.

“This type of programming suggests ‘status quo’ in country music and an industry uninterested in change,” says Watson.

Yet this is the industry that Nashville, as a city, continues to uplift.

Will Nashville actually be progressive and take steps to demand change in country music?

Some people like to say that country music is more successful than ever, that its global reach is unprecedented. But country music has never not been successful, particularly if money is the metric by which said success is measured. By providing the soundtrack to the lives of the political right, the anti-DEI, and the generally racist (disparate, progressive fans notwithstanding), country music enjoys unfettered access to a pre-built, unflinchingly loyal fan base.

Indeed, for every self-professed country music hater who also knows all the lyrics to Chris Stapleton’s “Tennessee Whiskey” or Carrie Underwood’s “Jesus Take the Wheel,” there are dozens of Morgan Wallen die-hards who couldn’t care less about a Drake collab — who, in fact, resent Wallen’s “punishment” for use of the n-word, a slur that “rappers are allowed to say all the time!”

At some point, however, Nashville will have to put dollars and cents aside and come to terms with its eager embrace of country music and its associated industry — that is, if the city wants to more accurately reflect the inclusivity it espouses.

Country’s bright lights and big stages may be pretty to look at, and they’re certainly a market differentiator as Nashville continues to compete for tourism revenue and caché. But promoting country music’s successes without acknowledging its flaws is akin to highlighting the hundreds of millions of dollars grossed by Tennessee via the antebellum exportation of cotton … without also acknowledging the enslavement of Black Americans that made it possible.

If Nashville is serious about being known as a welcoming, progressive enclave, city leaders can either back away from their country music ties or demand -- and enforce -- the industry's long overdue changes. Why should the industry be allowed access to a public space like the Bicentennial Capitol Mall State Park if the stage doesn't better reflect Nashville's diversity, among artists and musicians? Why has the CMA Fest been granted millions of dollars from the city's Metro Event Marketing Fund (administered by the CVC) when its stages and backstage production crews have been just as white?

And why is the CMA allowed to host its annual awards at Bridgestone, which is owned and controlled by the Sports Authority of Nashville and Davidson County, when the organization still bases eligibility for its most prestigious awards on metrics that nearly guarantee non-white exclusion?

As an example, to be eligible for CMA Single of the Year, a track must have reached the Top 10 of Billboard's Country Airplay Chart, Billboard's Hot Country Songs Chart, or the Country Aircheck Chart. But as previously mentioned, Black women are virtually un-played at country radio, and their charting success is even more dismal. No Black female country artist has ever made the Top 10. The highest charting song by a Black woman is Linda Martell's "Color Him Father," which reached the Top 25 ... in 1969.

There is precedent for this sort of municipal oversight of private industry. In 1946, when the NFL's Cleveland Rams were set to relocate to Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Coliseum Commission included an integration clause in the Rams' lease agreement. The team then signed former UCLA stars Kenny Washington and Woody Strode, thereby breaching the NFL's color line that had been in place since the early 30s.

The question is, how much do Nashville leaders care about this town's reputation, and its diverse citizenry? How long will they allow this music to represent Music City?

Andrea Williams is an opinion columnist for The Tennessean and curator of the Black Tennessee Voices initiative. Email her at [email protected] or follow her on X (formerly known as Twitter) at @AndreaWillWrite.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Nashville depends on country music and enables it not to change