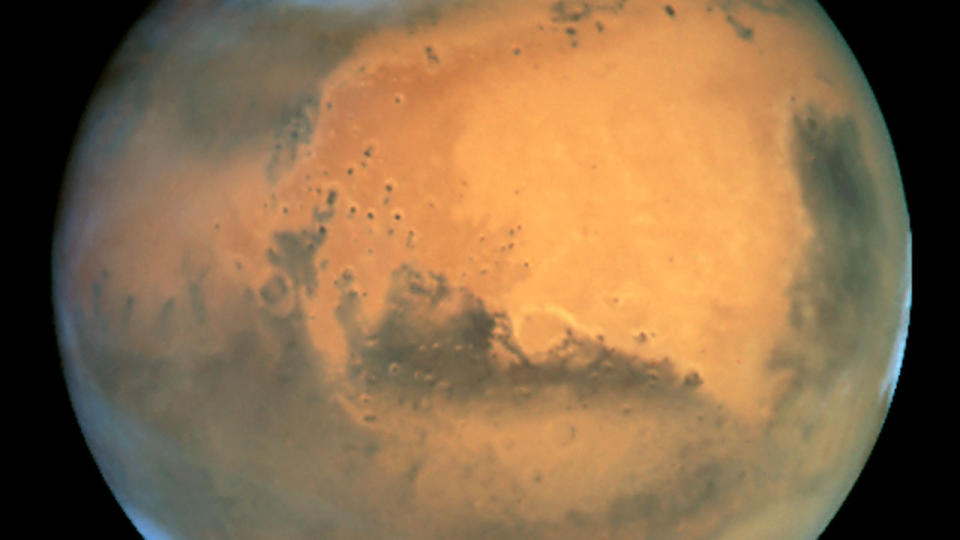

Ocean's worth of water may be buried within Mars — but can we get to it?

When you buy through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

Enough water to cover the surface of Mars has been discovered within the crust of the Red Planet by NASA's InSight mission. The ocean is buried between one and two kilometers (0.62 and 1.24 miles) underground.

InSight, which was a stationary lander during operation, touched down in the Elysium Planitia region on Mars in November 2018. It maintained its mission for four years and, armed with the first seismometer to be taken to the Red Planet, it detected 1,319 marsquakes.

Now, geophysicists Vashan Wright and Matthias Morzfeld of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, and professor of planetary science Michael Manga of the University of California, Berkeley, have used that seismometer data to discover water on the planet.

They combined the varying speeds of recorded marsquakes — documented as the quakes reverberated through the Red Planet's interior — to a mathematical model describing the physics of different types of rock in Mars' crust and mantle. It's exactly the same type of model that seismologists use on Earth to identify underground aquifers and oil fields.

Related: Is there liquid water on Mars today? Marsquake data could tell us

The results were startling, as the data showed that many of the seismic waves had passed through rock saturated with liquid water.

"Understanding the Martian water cycle is critical for understanding the evolution of the climate, surface and interior," said Wright in a press statement. "A useful starting point is to identify where water is and how much is there."

Once upon a time, Mars had lots of liquid water on its surface, with oceans, lakes and rivers, but the water disappeared about 3 billion years ago; today, Mars rovers explore dried up lakebeds and empty river channels. While some of Mars' water is locked up as ice in the polar caps and as permafrost down in the world's mid-latitudes, it had been assumed that the rest of Mars' water had escaped into space. Water vapor in the atmosphere was believed to have been broken apart by solar ultraviolet radiation and Mars' low gravity was thought unable to hang onto the hydrogen parts of that vapor, which would've then been carried away into space by the solar wind without a global magnetic field to shield against it. Meanwhile, the oxygen parts of the vapor would've oxidized the surface rocks, leading to the rust-red planet we see today. NASA's MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution) mission has even seen this process in action.

Now, however, it seems that not all of Mars' water was irretrievably lost this way. Some might have percolated into the crust instead, where it got stored in tiny cracks and pores within the planet's fractured igneous rock.

The trouble is, this water is deep. Very deep. The seismometer data suggests that it is present between depths of 11.5 and 20 km (7.1 and 12.4 miles) and there is no water at all in the crust above a depth of 5 km (3.1 miles). So, despite being the best evidence yet for liquid water on Mars, it is impractical for astronauts to reach it.

To illustrate why it is so unreachable, consider that the deepest hole ever dug on Earth is the Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia. Engineers in the Soviet Union spent 20 years digging the hole in an effort to reach the Earth's mantle, but drilling had to be aborted at a depth of 12.2 km (7.6 miles) because the temperature grew too great — 180 degrees Celsius (356 degrees Fahrenheit) — for the drill bit. It seems unlikely that equivalent drilling on Mars could be accomplished any time soon.

But even if we can't reach this water — yet — we can speculate about its implications both for the history of Mars and for the possibility of extant life on the Red Planet.

Related Stories:

— Equatorial Mars is surprisingly dry, NASA's InSight lander finds

— Water may have been on Mars much more recently than scientists thought, China's rover suggests

— Seismic waves inside Mars' core hint at how it became hostile to life

"Establishing that there is a big reservoir of liquid water provides some window into what the climate was like or could be like," said Manga. "And water is necessary for life as we know it. I don't see why [the underground reservoir] is not a habitable environment. It's certainly true on Earth — deep, deep mines host life, the bottom of the ocean hosts life. We haven't found any evidence for life on Mars, but at least we have identified a place that should, in principle, be able to sustain life."

The findings were published on Aug. 12 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.