‘We only got errors’: migrants struggle with asylum claim app at US-Mexico border

When they arrived in Ciudad Juárez on 17 March, across the US-Mexican border from El Paso, Texas, Nestor Quintero and his family were penniless, hungry and homeless. But their primary concern was getting their hands on a smartphone.

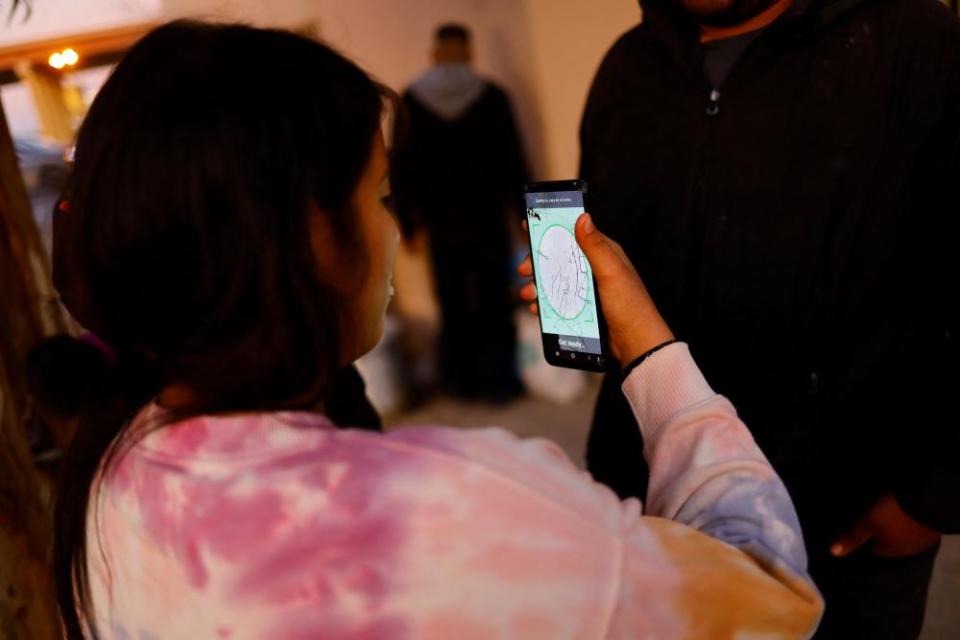

The 35-year-old Venezuelan migrant had found out in Tapachula, a city close to the Mexico-Guatemala border, that people hoping to enter the US to ask for asylum needed to secure an appointment through a recently introduced mobile phone app known as CBP One.

The app only works on smartphones and, to his dismay, Quintero had lost his phone during the harrowing trek across Panama’s Darién Gap, a roadless jungle on the Colombia-Panama border where tens of thousands of migrants heading north have risked their lives in the past year.

More than a week after working intermittently at a supermarket in Ciudad Juárez, Quintero earned enough money to buy a phone for 2,000 Mexican pesos, the equivalent of $114 (£90) . Initially, the family viewed the phone as their key to enter the US. But it soon became the main source of their frustration.

Related: El Paso braces for end of pandemic-era rules restricting migration from Mexico

“We woke up early every day and tried to get an appointment, but we only got errors, errors and errors,” Quintero said, while flashing a screenshot of a “System Error” message above the US Customs and Border Protection logo. His wife and two young daughters patiently sat next to him.

“We were desperate because we had no money and no food. So we surrendered ourselves at gate 36 of the border wall in El Paso.”

A month later, Quintero was 700 miles (1,125km) west, knocking on the metal door of Espacio Migrante, a migrant shelter in Tijuana, hoping to find out whether he was still eligible for a CBP One appointment.

After crossing into the US near El Paso, he and his family were detained by the US border patrol, flown to California and expelled back across the Mexican border to Tijuana.

There, Quintero had seen on social media that lawyers from the Immigrant Defenders Law Center (ImmDef), a social justice law firm based in Los Angeles that serves immigrants facing deportation, were giving a legal workshop at the shelter, to help asylum seekers.

Asylum in the US should not be dependent on whether or not your phone has the software updated

Lindsay Toczylowski of the Immigrant Defenders Law Center

“The government created this app and said that this is the only way for people to access the asylum system, while people here in Tijuana are fleeing their traffickers, or some other kind of danger. And if they don’t have a phone, they’re unable to access protection,” said Lindsay Toczylowski, executive director of ImmDef, adding: “Asylum in the US should not be dependent on whether or not your phone has the software updated.”

At noon, when Espacio Migrante opened its doors, at least 100 people, including Haitians, Venezuelans and Salvadorans, came in search of answers about CBP One.

The lawyers described the process for getting an appointment, but also explained that the chances of actually getting one were often slim, given the high demand and limited spots.

There was palpable confusion and anxiety among those gathered inside the shelter. The workshop came amid another phase of the intensifying humanitarian crisis in northern Mexico, where tens of thousands of people desperately fleeing violence, biting poverty and oppression in their home countries are hoping to cross into the US – with a coveted CBP One appointment or a change in policy.

At one minute to midnight on 11 May, the US will discontinue the obscure public health measure known as Title 42, implemented during the coronavirus pandemic by Donald Trump and continued, amid court battles, under Joe Biden.

Title 42 has allowed the federal authorities to summarily expel migrants back across the US-Mexico border – 2.7m times under the Biden administration alone – without allowing them to exercise their right to claim asylum.

The US government has projected that daily unauthorized border crossings could more than double to as many as 13,000 once such expulsions are halted, and is sending troops to support the border patrol. Fears of fresh chaos and misery abound, in contrast to Joe Biden’s campaign pledges of fairer and smoother systems.

Just hours before the legal presentation started at the Espacio Migrante shelter, the Biden administration unveiled its strategy to deter migration when Title 42 ends. Officials announced they would open processing centers in Colombia and Guatemala in a bid to encourage migrants to wait there for a chance to enter the US or a third country legally, as opposed to illegally crossing the US-Mexico border – or just turning up at border crossings to claim asylum without an appointment.

The US government has also been working on a highly controversial measure that would bar migrants from asylum if they enter the country illegally after failing to seek humanitarian protection in a third country they transited on their journey north.

When Title 42 ends, the US will revert to using the law known as Title 8. The government plans speedy processing of asylum seekers at the border, prompting immigrant advocates to complain that the process will be unfairly hasty. Deportation will be the result for many migrants, who are already in dire straits – with the Biden administration accused by progressives of hewing too closely to Trump’s hardline approach.

In Tijuana, migrants last week were unsure about how a dizzying array of Biden administration policy changes in recent weeks and months could affect them. Most who spoke to the Guardian were focused on obtaining an appointment to apply for asylum and receiving a CBP One confirmation email. Problems with the app have been well-documented, including families not being able to get appointments together.

“We cried every day because we wondered why many people got appointments and us with little kids couldn’t,” said Quintero, who left Carabobo, in northern Venezuela, after an opposition politician he had worked for suddenly disappeared.

“I can’t go back to Venezuela. We don’t have freedom of speech,” he said.

And the Guardian has reported that many other vulnerable migrants, including those with darker skin tones, haven’t been able to register to secure an appointment, despite daily attempts.

Towards the end of the lawyers’ presentation, another Venezuelan family sat outside the shelter, seeking shade in the strong sunshine. Marlin Fernández, 28, and Enders Pérez, 29, and their three daughters had been staying at the shelter since 29 March, after living in Tapachula for six months.

Fernández said that many women she met in Tapachula told her they had been sexually abused while on their way to northern Mexico, the only area where migrants can secure a CBP One appointment, due to a geographic limit imposed by the US. As they were traversing Mexico, Fernández said, a masked man entered the bus they were traveling on and took all their money.

But the family pushed onward to Tijuana, which they had heard was relatively safe compared to other Mexican border cities beset by cartel violence.

It was also the area where US officials were processing some of the highest numbers of asylum seekers.

Enrique Lucero, director of Tijuana’s office of migrant affairs, said that more than 16,000 migrants in Tijuana have secured CBP One appointments so far, or roughly 200 each day. About 6,600 of them were Russians. Haitians and Venezuelans have received the second- and third-highest number of appointments, Lucero said.

Fernández and Pérez desperately wanted to make it to the US, but they said they would like to do it the “right way”. But trying to do so was proving an ordeal.

“Something was wrong with my photo. Every time I tried, it just froze,” Fernández said, while breastfeeding her youngest daughter. “But one day my photo was saved, but then it showed an error [message]. I pressed ‘send’ again and received the same error message. I pressed ‘send’ again many times until it worked.”

Fernández and Pérez jumped and celebrated, but when the confirmation email arrived in Fernández’s inbox, they were confused. She and her family were asked to arrive at 6am on 3 May at the port of entry connecting Matamoros in Mexico with Brownsville, Texas – a crossing almost 2,000 miles (3,200km) away at the other end of the US-Mexico border.

“The night we got the appointments, a group of people arrived here from Matamoros and told us they were asked to leave the bus they were traveling in and that one of the passengers was kidnapped,” said Fernández.

But they couldn’t afford to fly to Matamoros. Broke and scared but determined, they chose a 20-hour bus ride there, saying: “We’ve heard that all shelters are full. Hopefully we don’t end up sleeping in the street.”

The family ended up entering the US and into the legal process. They were also given an immigration court date in October.

On their first night on US soil, Fernández met a Mexican woman who offered for the family to sleep at her home. Unable to cover the traveling expenses to New York City, their intended final destination, ImmDef provided them with bus tickets to San Antonio, Texas, where they will be placed in a shelter.