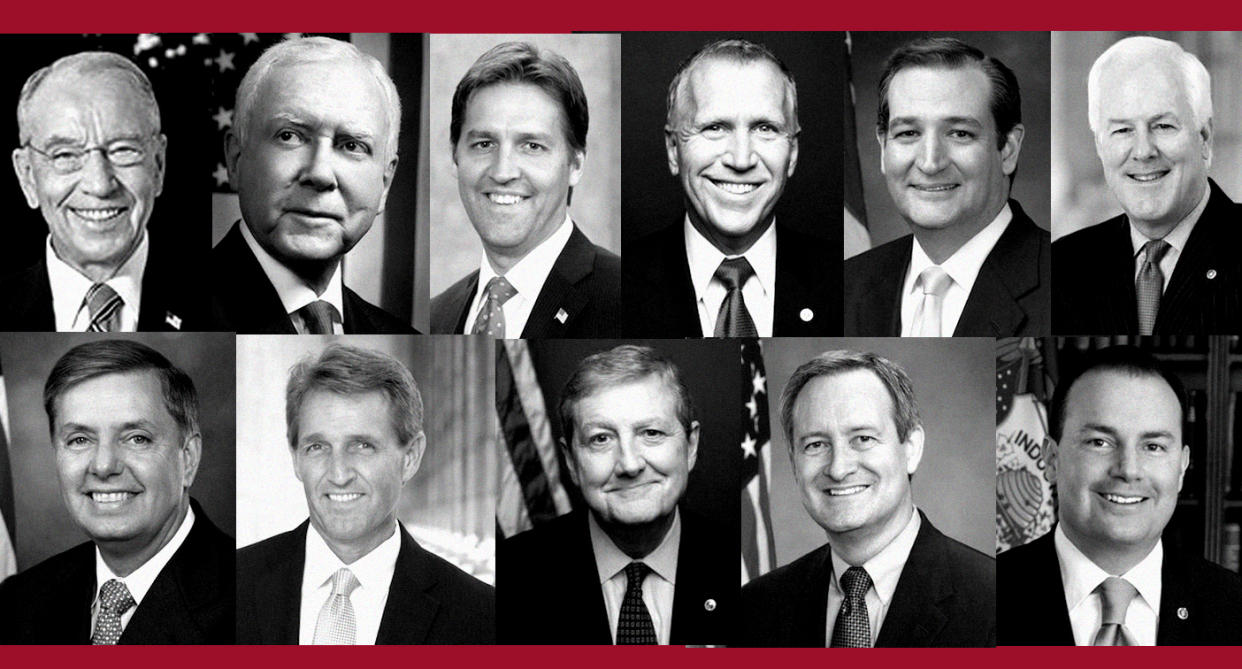

Republican men — and not a single GOP woman — will be Christine Blasey Ford's interrogators on the Senate Judiciary Committee

WASHINGTON — Next week, Christine Blasey Ford will likely face intense questioning from Republicans on the Senate Judiciary Committee about the truthfulness of her accusations against Brett Kavanaugh, the Supreme Court nominee, who she says attempted to rape her during a party in the 1980s. Her turn on Capitol Hill could decide Kavanaugh’s suddenly uncertain fate, as well as the Supreme Court’s direction for a generation.

Ford will face questions from the 11 Republicans on the Senate Judiciary Committee, all of them men, with an average age of 62. (The chairman, Chuck Grassley of Iowa, the second-oldest sitting senator, is 85.) In the committee’s 202-year history, it has not had a single Republican woman. Four of the 10 Democrats are women, including ranking member Sen. Dianne Feinstein of California, who is a few months older than Grassley. The committee has never been chaired by a woman.

The spectacle of Ford, 51, being interrogated about her sexual history by older men could present an uncomfortable sight that the White House may take great pains to avoid. The outrage over that discrepancy, however, is already building. “In the year 2018, a group of white men has essentially complete control over lifetime nominations to an entire branch of government,” tweeted Robert Reich, the former Labor secretary and current Berkeley professor. The message was retweeted more than 2,000 times.

The lack of Republican women on the Senate Judiciary Committee is striking, though somewhat difficult to explain. The first Republican woman sent to the Senate by voters was Margaret Chase Smith, in 1948 (two other women had been earlier appointed to the chamber). The following three decades saw only two more Republican women join her ranks. The first held a seat from Nebraska from April until November of 1954. The second woman held the same Nebraska seat for the following six weeks, until that year’s end. After that, no woman was elected to the Senate on the Republican ticket until Nancy Kassebaum of Kansas in 1978.

In the last 40 years, use of the judiciary to advance ideological goals has rendered the process of nominating judges highly political, with nominees evaluated on a narrow range of cultural issues, notably abortion, gun control and, until recently, gay marriage. That has tended to turn the Senate Judiciary into a hotbed of assertive ideologues, including, recently, Jeff Sessions and Ted Cruz. GOP women have made their contributions elsewhere, effectively ceding judicial nominations to their male counterparts.

It is not clear just how much the late-middle-aged Republicans on Senate Judiciary can — or want to — understand the sexual trauma Ford claims to have suffered at Kavanaugh’s hands, and how that trauma has affected her throughout her adult years. Hatch has already dismissed Ford as potentially “mixed up” in the charges she’s made. As for Kavanaugh, Hatch mused that “it would be hard for senators not to consider who he is today,” rather than evaluate him on allegations about his behavior as a teenager.

Hatch’s dismissal of Ford recalled similar remarks he made 27 years ago, during the confirmation hearing for Justice Clarence Thomas. A former subordinate, Anita Hill, testified she had been sexually harassed by Thomas in her job at the Department of Education. At the time, Hatch said, “There’s no question in my mind she was coached by special interest groups.” He added that Hill may have invented her allegations from a reading of “The Exorcist,” a horror novel about demonic possession.

It is a replay of the Hill hearings that Republicans badly want to avoid if and when Kavanaugh and Ford testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee (a hearing has been scheduled for Monday). Back then, societal tolerance for sexually inappropriate behavior by men was much greater than it is now. Even so, many remember with bitter dismay the treatment Hill received for coming forward. Among the culprits at the time was Joe Biden, the future Democratic vice president, then a senator representing Delaware and chairman of the Judiciary Committee. Biden questioned Hill skeptically, and declined to call another witness who might have corroborated her charges. Hill also faced an aggressive line of inquiry from Arlen Specter, Republican of Pennsylvania.

A similar treatment of Hill could prove disastrous politically, given the animosity many women already feel towards the Trump administration. According to Boston College political scientist David Hopkins, among the 41 states that had held primaries through mid-August, 41 percent of the victors on the Democratic side were women. A president himself accused by more than a dozen women of sexual assault pushing through the nomination of an accused sexual assailant could further galvanize Democrats in November’s midterms.

That has some wondering whether the hearing will go through — and, if it does, how hard 11 men will work to discredit a single woman.

_____

More Yahoo News stories on the Supreme Court:

New Kavanaugh allegations don’t change the fact that it’s all about politics

Brett Kavanaugh’s ex-boss: There’s no basis to demand his recusal from Mueller cases

Voting rights advocates wary of Kavanaugh’s nomination to Supreme Court

Can the Democrats do to Brett Kavanaugh what they did to Robert Bork?

Unborkable: Kavanaugh heads into confirmation hearings on cruise control