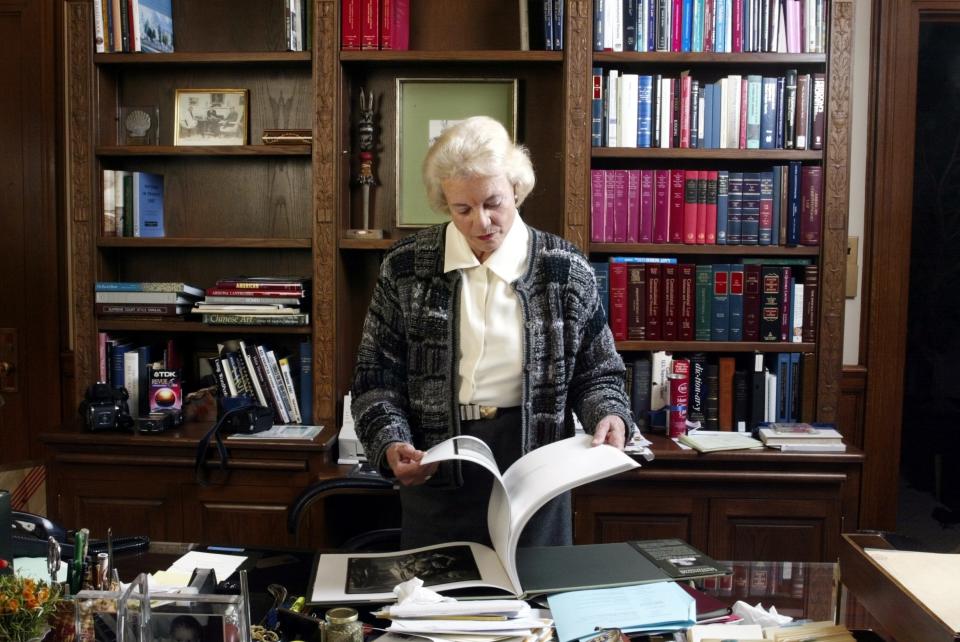

Sandra Day O'Connor, the first woman to serve on the Supreme Court, dies at 93

WASHINGTON – Retired Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, the first woman to serve on the nation's highest court and a crucial swing vote during her nearly 25-year tenure, died on Friday. She was 93.

A key figure in landmark Supreme Court cases dealing with abortion, affirmative action and civil rights, O’Connor retired in 2006 and announced in 2018 that she had been diagnosed with dementia and would withdraw from public life.

O'Connor was President Ronald Reagan's first nominee to the Supreme Court, joining the court in 1981 after an already notable career that included serving as the majority leader in Arizona’s state Senate – the first woman to hold that title in the nation.

She died in Phoenix of complications related to advanced dementia and a respiratory illness, according to a statement from the Supreme Court.

"A daughter of the American Southwest, Sandra Day O'Connor blazed an historic trail as our nation's first female justice," Chief Justice John Roberts said in a statement.

"She met that challenge with undaunted determination, indisputable ability, and engaging candor," he said. "We at the Supreme Court mourn the loss of a beloved colleague, a fiercely independent defender of the rule of law, and an eloquent advocate for civics education."

During much of her time on the court, which spanned three chief justices, O'Connor was a swing vote in many blockbuster cases and, in part, because of that, was arguably the most powerful woman in the nation. She helped craft a 1992 opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey that upheld a woman's right to an abortion but permitted states to impose additional restrictions. That decision, along with the court's 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade, was overruled by the court's conservative majority last year.

Opinions: 'Audience of one.' A look at some of Sandra Day O'Connor's biggest Supreme Court decisions

O'Connor wrote for the majority in Grutter v. Bollinger, a 2003 decision that permitted universities to consider race as a factor in admissions to boost minority enrollment as long as they also weighed other characteristics unique to individual applicants. That precedent was abandoned earlier this year when the Supreme Court struck down affirmative action policies at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina.

O’Connor joined the court's 5-4 ruling that decided the 2000 presidential election in favor of George W. Bush. She later questioned whether the court should have gotten involved, telling the Chicago Tribune that it "stirred up the public" and "gave the court a less-than-perfect reputation."

Despite her influence, O’Connor rejected the "swing vote" label.

“I don’t like that term," she told NPR in 2013. "I don’t think any justice ? and I hope I was not one ? would swing back and forth and just try to make decisions not based on legal principles but on where you thought the direction should go.”

Who was Sandra Day O'Connor?

Born in Texas, O’Connor grew up on a cattle ranch in rural Arizona, where she developed a skepticism of the federal government's land management policies – a perception some observers say influenced her commitment to federalism and state rights on the court. She graduated high school at 16 and enrolled at Stanford University, where she later continued to study law.

Early in her career, she struggled to find work. She remembered a bulletin board noting law firms interested in interviewing its graduates for jobs.

"I called at least 40 of those firms asking for an interview, and not one of them would give me an interview," O’Connor told NPR. "I was a woman. They said they don’t hire women. It was a total shock to me. … I had done well in law school, and it never entered my mind that I couldn’t get an interview. That’s the way it was in those days."

She approached the county attorney in San Mateo, California, because he had hired a woman once. He said O’Connor seemed like a good hire but he had no money left in his budget and no space left in his office.

O’Connor offered to work for free until money was available, which took several months.

“And that was my first job as a lawyer,” O’Connor said. “I worked for no pay and I put my desk in there with the secretary. But I loved my job. It was great.”

After the Supreme Court

O'Connor announced her retirement – earlier than some expected – to care for her husband, who had advanced Alzheimer's and who died in 2009. She was succeeded by Samuel Alito, who is now the second-most senior associate justice on the Supreme Court.

After an active post-court career – including serving as chancellor of the College of William & Mary in Virginia – O’Connor largely remained out of public view after announcing her dementia diagnosis in 2018.

"While the final chapter of my life with dementia may be trying, nothing has diminished my gratitude and deep appreciation for the countless blessings in my life," she wrote in a letter released by the court at the time.

"How fortunate I feel to be an American and to have been presented with the remarkable opportunities available to the citizens of our country," she added. “As a young cowgirl from the Arizona desert, I never could have imagined that one day I would become the first woman justice on the U.S. Supreme Court."

O'Connor’s legacy

In her later years, O’Connor wrote a memoir, a history of the Supreme Court and several children’s books. She also founded iCivics, an online program to instill an understanding of government in a new generation. She frequently spoke in defense of an independent judiciary.

She also remained active by sitting on federal appeals cases for years after her retirement from the Supreme Court.

Ruth McGregor, a former chief justice of the Arizona Supreme Court who served as a law clerk for O’Connor in her first year, recalled mailbags delivered to her chambers with letters of support from across the country.

Who are the nine justices? Your guide to the current Supreme Court justices: ages, who is chief justice, more.

“It’s easy to forget people in a public position have a personal side,” McGregor told the Arizona Republic, but O’Connor was thoughtful and warm. “She’s just present in her friends’ lives.”

O’Connor was happy to break barriers for women but didn’t dwell on her gender.

“It really doesn’t come down to how I feel about (a case) as a woman,” she would say. Quoting another female judge’s observation, she said, “At the end of the day, a wise old woman and a wise old man are going to reach the same decision.”

Even so, after giving notice of her retirement, O’Connor quietly expressed hope that President George W. Bush would replace her with a woman.

When it didn’t happen, O’Connor admitted to doubting herself.

“I’ve often said it’s wonderful to be the first to do something, but I didn’t want to be the last,” she told C-SPAN. “If I didn’t do a good job, it might have been the last. And indeed, when I retired, I was not replaced then by a woman, which gives one pause to think, ‘Oh, what did I do wrong that led to this?’”

Today, four women serve on the nation's highest court.

Contributing: Arizona Republic.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Sandra Day O'Connor, first woman to serve on Supreme Court, dies at 93