Scientists build intricate Neolithic family tree from 7,000-year-old DNA

Around 12,000 years ago, humans shifted away from a hunter gatherer lifestyle and into a neolithic society based around farming. This change still has a massive impact on our lives, but it is difficult to assess how these communities migrated and what their social networks may have looked like.

[Related: Neolithic surgeons might have practiced their skull-drilling techniques on cows.]

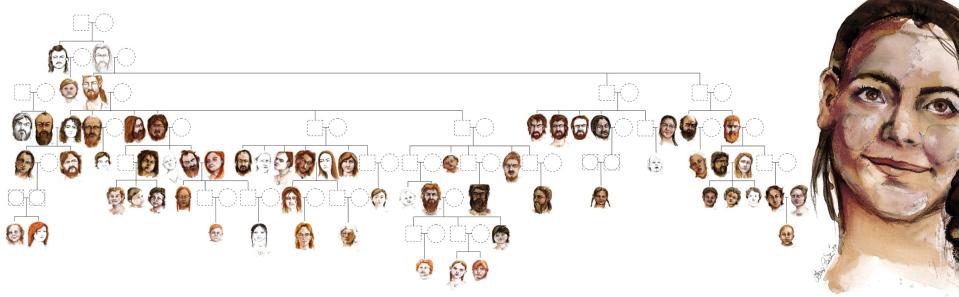

In a study published July 26 in the journal Nature, a team of scientists used roughly 7,000 year-old DNA to reconstruct two massive family trees. Their findings suggest that some females left their home community to join another. It also provides evidence of stable health conditions and a supportive social network within one prehistoric community in Europe.

One way scientists determine relationships are through burials, inferring who may have been related through inferences of funeral practices of the time. But actual genetic analysis is tricky. The Paris Basin region in northern France has several monumental funerary sites that archaeologists believe were built for the more “elite” members of prehistoric society.

However, the nearby site of Gurgy ‘Les Noisats’ is one of the largest Neolithic funerary sites that does not have a monument. This sparked questions about the different burial practices of the time.

In this new study, the team used ancient genome-wide data excavated from Les Noisats between 2004 and 2007. The remains of 94 individuals buried in Gurgy are dated to approximately 4,850 to 4,500 BCE. The team combined this ancient genome data with strontium isotope analysis, mitochondrial DNA to show maternal lineages, and Y-chromosome data for patrilineal lineages, age-at-death, and genetic sex to build two family trees.

The first tree connects 64 individuals over seven generations, and is the largest pedigree reconstructed from ancient DNA to date. The second family tree connects 12 individuals over five generations.

“Since the beginning of the excavation, we found evidence of a complete control of the funerary space and only very few overlapping burials, which felt like the site was managed by a group of closely related individuals, or at least by people who knew who was buried where,” study co-author and University of Bordeaux archaeo-anthropologist Stéphane Rottier said in a statement.

The team also found a positive correlation between spatial and genetic distances of the remains, which indicates that the deceased were likely to be buried close to a relative. When examining the pedigrees further, they also saw a strong pattern along paternal lines. Each generation, it seems, is almost exclusively linked to the generation before through the biological father. The entire Gurgy group can be connected through the paternal line.

[Related: Neanderthal genomes reveal family bonds from 54,000 years ago.]

On the other side of the family trees, evidence from mitochondrial lineages and the strontium stable isotopes show a non-local origin of most of the women. This suggests Gurgy had a practice called patrilocality, where sons stayed where they were born and then had children with women from outside of the community. By contrast, most of the lineage of adult daughters are missing, suggesting there might have been a reciprocal exchange system with other communities. The newer female individuals were only very distantly related to each other, which shows that they likely came from a network of communities nearby instead of just one group. There could have been a relatively large exchange network of many groups in the region.

“We observe a large number of full siblings who have reached reproductive age. Combined with the expected equal number of females and significant number of deceased infants, this indicates large family sizes, a high fertility rate and generally stable conditions of health and nutrition, which is quite striking for such ancient times,” study co-author and Ghent University paleogeneticist Ma?té Rivollat said in a statement.

Additionally, the team could point to one male individual from which everyone in the largest family tree was descended. This “founding father” of the cemetery has a unique burial, with skeletal remains buried as a secondary deposit inside the grave pit of a woman. This indicates that his bones must have been brought from where he originally died to be reburied at Gurgy.

“He must have represented a person of great significance for the founders of the Gurgy site to be brought there after a primary burial somewhere else,” co-author and University of Bordeaux paleogeneticist Marie-France Deguilloux said in a statement.

While the main pedigree spans seven generations, the demographic profile suggests that a Gurgy itself was probably only used for three to four generations, or approximately one century. Nevertheless, these lengthy pedigrees represent a step forward in our understanding of the social organization of past societies.

“Only with the major advances in our field in very recent years and the full integration of context data it was possible to carry out such an extraordinary study,” study co-author and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology molecular anthropologist Wolfgang Haak said in a statement. “It is a dream come true for every anthropologist and archaeologist and opens up a new avenue for the study of the ancient human past.”

Solve the daily Crossword