State's top doctor: Measles outbreak likely in Michigan because of low vaccination rates

Michigan is ripe for a measles outbreak, as cases of the highly contagious disease climb across the U.S. and globally, and vaccination rates for recommended childhood immunizations have dropped to 66% among Michigan toddlers, state health officials say. It's a low not seen in Michigan in more than a decade.

"It is a matter of when, not if, we start seeing measles cases in Michigan," Dr. Natasha Bagdasarian, the state's chief medical executive, told the Free Press. "Here we are with three cases, three discrete introductions, in the space of less than two weeks, and it's only February. The number of cases across the U.S. is ticking up ... the more exposures we have here in Michigan, the more people risk getting exposed."

Potentially hundreds of Michiganders were exposed to the virus from Feb. 27-March 1 at two hospital emergency departments, two urgent care centers and a pharmacy in Wayne and Washtenaw counties, when two infected adults sought treatment for symptoms. A third person, an unvaccinated child from Oakland County, also was infected with measles, state health officials announced Feb. 23.

The cases sparked a scramble among Michigan public health leaders to track down everyone who might have crossed paths with the infected people and determine whether they all had been fully vaccinated against measles. The virus is so contagious that 90% people who are unvaccinated and exposed will become infected.

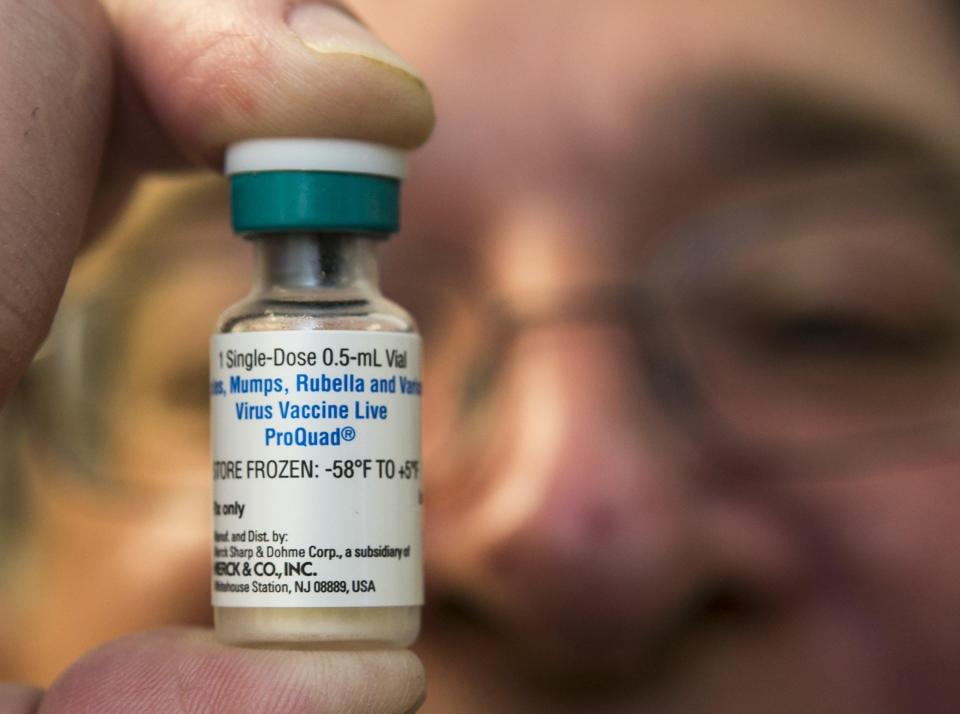

Spread of the virus can be thwarted, however, if a dose of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine, known as the MMR, can be given within 72 hours of exposure, or intravenous immunoglobulin can be administered within six days of exposure.

Preventing infection is important, Bagdasarian said, because measles is not a mild illness.

"We've had the vaccine since 1963, and before the vaccine was available, every year across the U.S., between 400 and 500 people died," she said. "Four hundred to 500 people may not seem like ... huge numbers, but it is a lot, especially if you're talking about your loved one or your child."

The virus causes high fever, cough, runny nose, conjunctivitis (red, inflamed eyes) and rash that typically starts at the head and spreads down the body. People are contagious up to four days before symptoms appear and the rate of complications is high, Bagdasarian said.

"About 20% of folks who go on to develop those symptoms end up hospitalized," she said. "The complications can include things like encephalitis or swelling around the brain, severe pneumonia and even death. All of those complications are preventable with the vaccine. The efficacy of the vaccine is 93% if you get a single dose and between 97% and 98%, if you get two doses.

"We are encouraging all Michiganders to get vaccinated, especially if you are planning any travel in the near future."

School-age vaccination waivers are rising in Michigan

The state health department doesn't keep track of MMR vaccine coverage among adults in Michigan, so it's unclear exactly how much of the state's total population is considered fully immune to measles.

Childhood vaccinations, however, are recorded by the Michigan Care Improvement Registry, which provides among the clearest snapshots of vaccine coverage in the state's toddlers and school-age children.

The Michigan Public Health Code requires children enrolled in public or private schools, licensed day care centers and preschools to be immunized for 10 diseases: diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (DTP, DTaP, Tdap); polio; measles, mumps and rubella (MMR); hepatitis B; meningococcal conjugate, and varicella (chickenpox).

Unless there is a medical reason to prevent children from being vaccinated, parents who want to opt out of any of the required vaccines for their kids must get a waiver from their county health department to enroll them in school. They can seek waivers that allow them to skip vaccines if they have philosophical or religious objections to them.

Tracking the volume of vaccine waivers in a county or even individual school can provide a view of how vulnerable children in certain communities are to contracting and spreading vaccine-preventable diseases.

Among school-age kids in Michigan, the number whose parents have gotten waivers to exempt them from at least one school-required vaccine is on the rise.

In 2015, 3.1% of Michigan schoolchildren had vaccine waivers that allowed them to skip one or all of the state-mandated vaccines or allowed them to deviate from the recommended immunization schedule.

In the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic, the number of children with waivers for at least one of the required vaccines in Michigan rose to nearly 18,000 — which amounts to roughly 4.8% of kids enrolled in public and private schools statewide in 2022, according to the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.

In one Michigan county, Houghton, nearly 1 in 5 school-age children had exemptions for at least one school-mandated vaccine in 2022, according to state data. That western Upper Peninsula county has the state's highest rate of school vaccine waivers, with 18.9% foregoing a required immunization.

In the following five additional counties, vaccine waivers exceeded 10% of enrolled students:

Oscoda: 15.5%

Lapeer: 11.8%

Benzie 11.4%

Leelanau: 10.7%

Kalkaska: 10.2%

Four other Michigan counties round out those with the highest percentage of vaccine waivers in 2022:

Antrim: 9.5%

St. Clair: 8.8%

Emmet: 8.7%

Livingston: 8.7%

"We've seen this huge drop in children who are fully vaccinated, and unfortunately, it's just not coming back up to the levels that we were at before," said Dr. Aarti Raheja, a pediatrician at the University of Michigan Health C.S. Mott Children's Hospital and a member of the Michigan Advisory Council for Immunizations. "That is concerning because it puts us at risk for these vaccine-preventable diseases, like we're seeing with measles."

A challenge: Overcoming pandemic's vaccine controversy

During the pandemic, Raheja said many children missed their annual exams and other checkups, which ordinarily is when they would be vaccinated.

"Our kids weren't being seen in clinic," Raheja said. "So they weren't getting opportunities to get vaccinated. Several children got behind with that and we just haven't been able to catch them up."

Additionally, some parents who might not have given a second thought to vaccinating their kids in the past grew more hesitant about vaccines because of misconceptions that proliferated during the pandemic, said Dr. Jennifer Morse, medical director for three public health departments covering 19 counties in central Michigan — Mid-Michigan District Health Department, Central Michigan District Health Department, and District Health Department No. 10.

"Instead of seeing immunizations as lifesaving, amazing medical tools, they are now really being seen as controversial, political, freedom-of-choice devices," Morse said. "How do we separate that out again, and make people see that these medical miracles are on the same plain as clean water and sewage? ... I'm not sure how to do that."

Morse, who also is a member of the Michigan State Medical Society board of directors, emphasized that she was speaking on her own behalf, and not on behalf of the health departments she oversees "because I don't want to politicize my health departments." But, she said, it is extremely challenging these days for public health leaders to even broach the subject of vaccines in their communities.

"We try to work with our parents and our schools, but people are literally afraid to put out positive vaccine messages because they don't want to upset the population that we're working with," Morse said.

"We offer to do school vaccination clinics at any school that wants to have them. We offer walk-in hours, things like that, but we just really struggle with it in many of our areas. Many schools don't want to do school vaccine clinics anymore because they're afraid of backlash. The attitude toward vaccines is now that they're kind of a controversial topic."

As difficult as it can be a times, Morse said local health departments must continue to provide accurate vaccine information to parents pursuing waivers for their kids. Part of that is to inform parents that if there is a child with measles at school, unvaccinated students will have to stay home for 21 days after exposure.

"We are making sure parents know the risks to not vaccinating," Morse said. "There is the potential for exclusion from school as a method to stop outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases. For children who may not be vaccinated, we don't ever want them to not realize that could be a potential for their child. Not very often, but on occasion, we do succeed in getting a vaccine or two into children who maybe previously had parents who were not initially agreeable, but most of the time, we don't have a lot of success."

Falling short of needed herd immunity for measles

Michigan is one of only 15 states that allow for philosophical exemptions to mandated childhood vaccines, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. All 50 U.S. states allow schoolchildren to be able to waive school-required vaccines for medical reasons.

Those medical reasons can include a true allergy to a vaccine component as well as having an immunological condition that might make them unable to take live, attenuated vaccines like those that protect against measles or chickenpox, Raheja said.

Children who have had organ transplants, those who have HIV or kids who are being treated for cancer or autoimmune diseases could be among those who cannot get a vaccine.

But, Raheja said, those cases are "extraordinarily rare."

For the vast majority of children, "these vaccines are safe and effective at protecting against many serious and life-threatening diseases," she said. "With how infectious it is, and with measles cases on the rise around the world, we say measles is just a plane ride away.

"That's why it's really important that we have herd immunity, which occurs when a large portion of our population is immune to a disease to protect those who aren't. The percentage of the population that needs to be immune varies by disease and level of contagiousness. Measles is so contagious that we really need a high level of coverage to protect the vulnerable. We need 95% of the population to be fully vaccinated to achieve herd immunity, and our numbers are not there."

Who should be revaccinated?

Bagdasarian urged anyone who isn't up to date on measles vaccinations or isn't otherwise considered immune to get their shots now.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that the MMR vaccine be given to:

A first dose for children at 12-15 months old, with a booster dose administered between ages 4 and 6.

Anyone born during or after 1957 without evidence of immunity against measles or documentation of having been vaccinated with two doses of MMR vaccine. The second dose should be given no sooner than 28 days after the first.

People exposed to measles who cannot document immunity against the virus should get post-exposure prophylaxis — a dose of the vaccine to potentially provide protection within 72 hours of initial exposure, or immunoglobulin within six days of exposure.

Dr. Russell Faust, medical director of the Oakland County Health Division, encouraged even people who were born before 1957 — considered immune because they likely had the virus as children — to get vaccinated, especially if they're planning any kind of international travel.

People born between 1963 and 1967 who don't have documentation of which type of vaccine they received also should be revaccinated, he said.

Many people born after 1957 but before 1989 may have gotten only got one dose of the MMR vaccine. At the time, the CDC considered one dose fully vaccinated. The guidelines later changed, but people who fall in this group — now between ages of 35 and 67 — might want to consider an MMR booster, Faust said, especially if international travel is planned.

"Two doses are considered to be fully vaccinated," he said.

How to track your vaccination history

How can you find out how many doses of the MMR vaccine you've gotten?

Michigan natives born after Dec. 31, 1993, should find a relatively complete accounting of all the vaccinations they've received since infancy in the Michigan Care Improvement Registry, which was launched in 1998 with a goal of collecting Michigan childhood immunization records digitally that could be easily accessed by medical providers and schools, licensed child care providers and pharmacies.

Anyone age 18 or older can access their records in MCIR for free online through the Michigan Immunization Portal: mdhhsmiimmsportal.state.mi.us.

If you were born before Dec. 31, 1993, or didn’t grow up in Michigan, the MCIR database may not help you track your vaccination history.

Here are some tips on how to find more details:

If your parents are still living, ask whether they remember having you vaccinated as a child.

If your parents don’t remember or if they’re no longer living, you can check with the local health department in the county where you lived as a child.

Check with the school district or college you attended to find out whether those educational institutions have a record of your immunizations.

If you tried all that and still can't track down your immunization status, there's one more thing you can do: Ask your doctor for a blood test to check whether you have antibodies for measles or other vaccine-preventable diseases such as polio and chickenpox.

That test, however, isn't always covered by insurance. It might be a good idea to call ahead to find out what it will cost before getting an antibody test.

Another option: Just get another dose of the MMR vaccine to ensure you're covered.

"There is not typically any harm associated with getting an extra dose of the vaccine," Bagdasarian said. "But I think that based on your medical history, and based on your own unique risk profile, it's always a good idea to talk to your health care provider."

What if you're exposed?

If you realize that you might have been exposed to measles or have any concerns that you may be developing symptoms, the best thing to do is call your physician or the local health department, said Dr. Bobby Mukkamala, past president of the Michigan State Medical Society and board member and past chair of the American Medical Association.

"Be aware that measles is out there in southeast Michigan," Mukkamala said. "There have been three cases in rapid succession. It's a real risk.

"If somebody does start developing symptoms, even if they haven't been contacted by contact tracers, they should proactively say, 'Hey, I've got this sore throat now. I'm starting to get a rash.' They should immediately isolate and then contact the health department.

"You don't have to wait to be called."

Contact Kristen Shamus: [email protected]. Subscribe to the Free Press.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Michigan ripe for measles outbreak as vaccination rates drop

Solve the daily Crossword