The Supreme Court’s Big Gun Case Was Humiliating for the Justices

This is part of Opening Arguments, Slate’s coverage of the start of the latest Supreme Court term. We’re working to change the way the media covers the Supreme Court. Support our work when you join Slate Plus.

For Zackey Rahimi, the solution for just about every problem in life seems to be to shoot a gun in its general direction. In December 2019, he fired a shot at a bystander who’d seen him shove his girlfriend in a parking lot, then threatened to shoot his girlfriend too if she told anyone about it. When an acquaintance posted something rude about him on social media, he fired an AR-15 into their house. When he got into a car accident, he shot at the other driver; when a truck flashed its lights at him on the highway, he followed the driver off the exit and, for some reason, shot at a different car that was behind the offending truck. After Rahimi’s friend’s credit card was declined at a Whataburger, Rahimi pulled out a gun and fired several shots into the air, a choice that I doubt made terrified employees any more inclined to fulfill his order.

None of this was in dispute on Tuesday, when the Supreme Court heard oral arguments over Rahimi’s bid to keep his beloved guns. But it was also not much of a topic of conversation, as Justice Clarence Thomas claimed there existed only a “very thin record” in the case. Despite the court’s inability (or unwillingness) to highlight the horrifying facts of his case, it does seem as if enough conservatives will join the court’s progressives to reject Rahimi’s plea.

If it weren’t clear already, Zackey Rahimi has not demonstrated an ability to safely possess firearms. In early 2020, a Texas state court entered a protective order that, among other things, ordered him to stay away from his ex-girlfriend and barred him from having guns. But after police investigating the subsequent shootings searched his room and found a pistol, a rifle, and ammunition for both, Rahimi was charged with violating a federal law that prohibits people subject to protective orders from possessing guns. In federal district court, Rahimi challenged the law as a violation of his Second Amendment rights, but the judge was unconvinced. A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit—the country’s most conservative federal appeals court—affirmed in June 2022 the state’s right to take away Zackey Rahimi’s firearms.

A few weeks later, however, the Supreme Court blessed Rahimi with a chance to get his guns back. In an opinion penned by Thomas, the court held, in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, that restrictions on the right to bear arms are presumptively unconstitutional unless they are, in a judge’s learned opinion, consistent with the nation’s “historical tradition of firearm regulation.” The 5th Circuit withdrew its opinion in Rahimi’s case and issued another in which it changed its mind: Although the law embodies “salutary policy goals,” wrote Judge Cory T. Wilson, “our ancestors would never have accepted” it. Put differently, because the Framers did not disarm domestic abusers, who today shoot and kill an average of 70 women a month, modern lawmakers are powerless to do anything about it.

Since Bruen, lower court judges applying its test have been, to use a legal term of art, all over the place, a fact repeatedly highlighted during oral arguments by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who sought some, any, guidance on how the court should understand its own ruling. Again, lower courts are equally confused. One court, for example, decided that Florida’s ban on the sale of guns to 18-to-20-year-olds passed constitutional muster; another concluded that a federal law disarming people convicted of certain crimes perhaps did not.

A few judges have publicly aired their frustrations with the sudden analytical primacy of law-office history. “We are not experts in what white, wealthy, and male property owners thought about firearms regulation in 1791,” wrote one in 2022. “Yet we are now expected to play historian in the name of constitutional adjudication.” Another castigated the court for creating a game of “historical Where’s Waldo” that entails “mountains of work for district courts that must now deal with Bruen-related arguments in nearly every criminal case in which a firearm is found.”

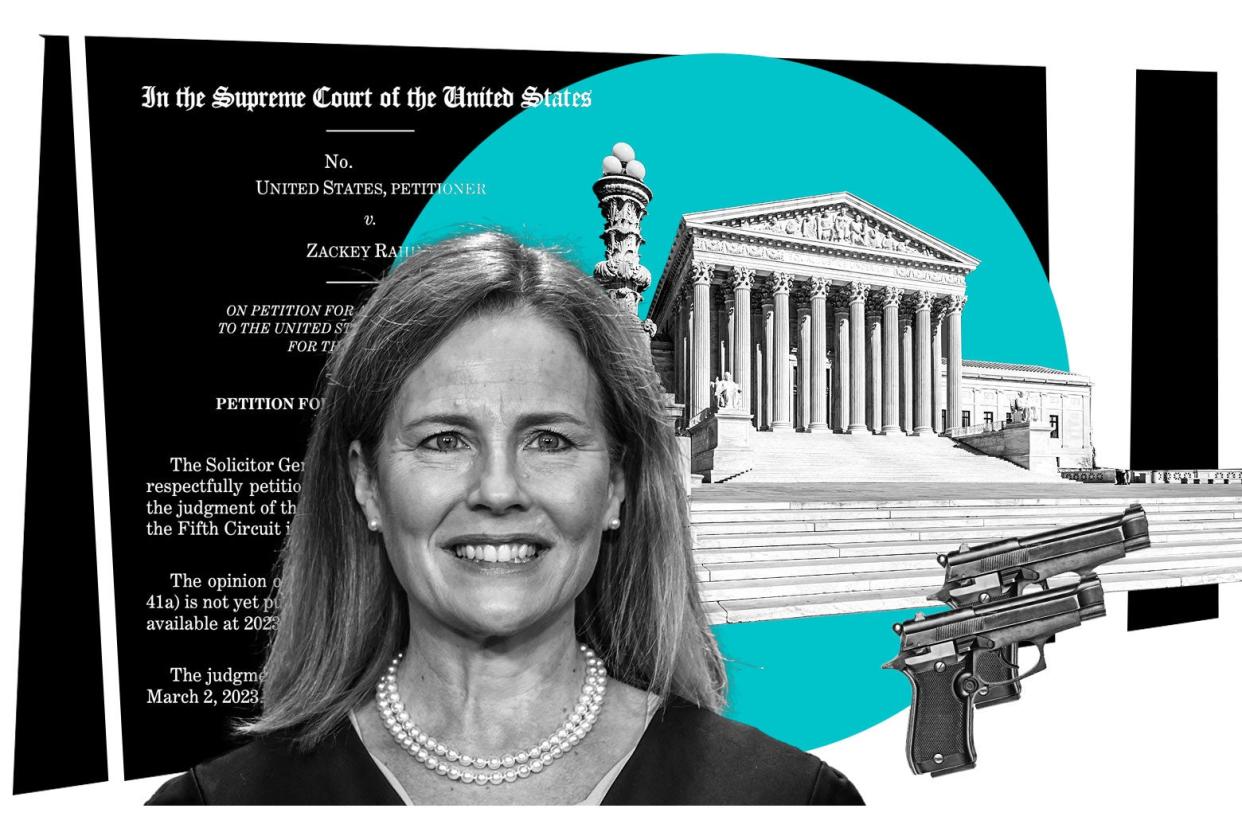

In taking up Rahimi’s case on Tuesday, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in its first major Second Amendment case since Bruen. The legal question in United States v. Rahimi is whether the federal law under which Rahimi was convicted violates the Second Amendment. The practical question is whether the court meant what it said in Bruen so literally that any legislative attempt to address America’s ongoing gun violence crisis must bow to whatever Clarence Thomas imagines that James Madison would have thought about it nearly 250 years ago.

Most of the debate on Tuesday was about the level of generality at which a modern law is supported by “history and tradition.” In Bruen, Thomas wrote that the government must identify a historical “analogue,” but not necessarily a historical “twin.” But both sides, of course, have different views about exactly how close the familial relationship needs to be. In Rahimi, the government argues that a “history and tradition” of disarming “dangerous” people is enough to uphold the law. Rahimi argues that a purported lack of a “history and tradition” of outright bans on gun possession means that the law is unconstitutional, and that the government has no choice but to restore Rahimi’s right to wave a gun around when denied access to fast-food hamburgers of his choice.

This argument is bold, in the same way that Captain Smith’s choice to navigate the Titanic into an iceberg field was bold. The modern concept of protective orders, after all, did not exist at the founding, which makes the absence of laws disarming people subject to protective orders not as dispositive as your average National Rifle Association lifetime member would think. Today’s firearms are also far deadlier than Colonial-era firearms: In about two-thirds of fatal mass shootings between 2014 and 2019, the perpetrator either killed at least one partner or family member or had a history of domestic violence, according to an amicus brief filed by a gun safety group. In the context of a real-life epidemic of deadly intimate partner violence, the fact that the Framers did not disarm abusers in 1791 does not mean they would not have done so if abusers in 1791 murdered as many people as they do in 2023.

A few justices raised concerns about the problems inherent in empowering judges and lawmakers to determine who is “dangerous” or “irresponsible” enough to lose their Second Amendment rights. None, however, seemed to think that Zackey Rahimi would not qualify. After Chief Justice John Roberts asked if Rahimi’s counsel, J. Matthew Wright, would concede that his client is a “dangerous person,” Wright, ever the zealous advocate, asked for a definition of the term. Roberts’ incredulous reply—“Well, it means someone who’s shooting, you know, at people. That’s a good start”—drew nervous laughter from the gallery.

Burdened with a difficult set of facts, Wright pushed a different, narrower argument: that the law at issue did not provide Rahimi enough process before the government took his guns away. But Rahimi’s case is a facial challenge under the Second Amendment, not a due process challenge, and a few justices grew frustrated with Wright for evading the question. At various points, Roberts and Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Neil Gorsuch all suggested that resolving problems with civil protective order processes is simply a task for another day. If there are “circumstances where someone could be shown to be sufficiently dangerous that the firearm can be taken from him,” Roberts asked, “why isn’t that the end of the case?”

Justice Elena Kagan was even more withering in her criticism. “I feel like you’re running away from your argument, you know, because the implications of your argument are just so untenable that you have to say, ‘No, that’s not really my argument,’ ” she said, noting that Wright’s logic would jeopardize a “wide variety” of laws that disarm people who pose an “obvious” danger to others. “I guess I’m asking you to clarify your argument, because you seem to be running away from it because you can’t stand what the consequences of it are.”

After oral argument, it seems likely that the court will back away from the most extreme iteration of Bruen. (As the New York Times’ Linda Greenhouse noted, many of the pro–Second Amendment amici in Bruen are conspicuously silent in Rahimi because even the conservative legal movement’s most unapologetic gun rights proponents probably do not want to see “SUPREME COURT UPHOLDS GUN RIGHTS OF DOMESTIC ABUSERS” splashed across the top of, well, the New York Times.) At one point, Jackson invoked the case’s implications in the aftermath of the recent mass shooting in Maine, in which 18 people were killed. A result in Rahimi that clarifies Bruen would be welcome news for lawmakers whose constituents, as Jackson put it, are asking them to “do something”—but who, as of now, aren’t sure what the court will allow.

To the extent that the justices felt annoyed or embarrassed by the proceedings on Tuesday, they have no one to blame but themselves. Everything Wright argued on Rahimi’s behalf flows directly from Bruen, a jurisprudential train wreck that Clarence Thomas slapped on Supreme Court letterhead while putting together his luxury vacation plans for the summer. This is the kind of thing that will occasionally happen as long as the court is controlled by a six-justice conservative supermajority: When there is nothing to check Thomas and Company’s enthusiasm for repackaging Federalist Society dogma as constitutional law, sometimes they will make a mess that they’ll have to go back and clean up.