Will the Supreme Court Flunk Its Domestic Violence Test?

This is part of Opening Arguments, Slate’s coverage of the start of the latest Supreme Court term. We’re working to change the way the media covers the Supreme Court. Support our work when you join Slate Plus.

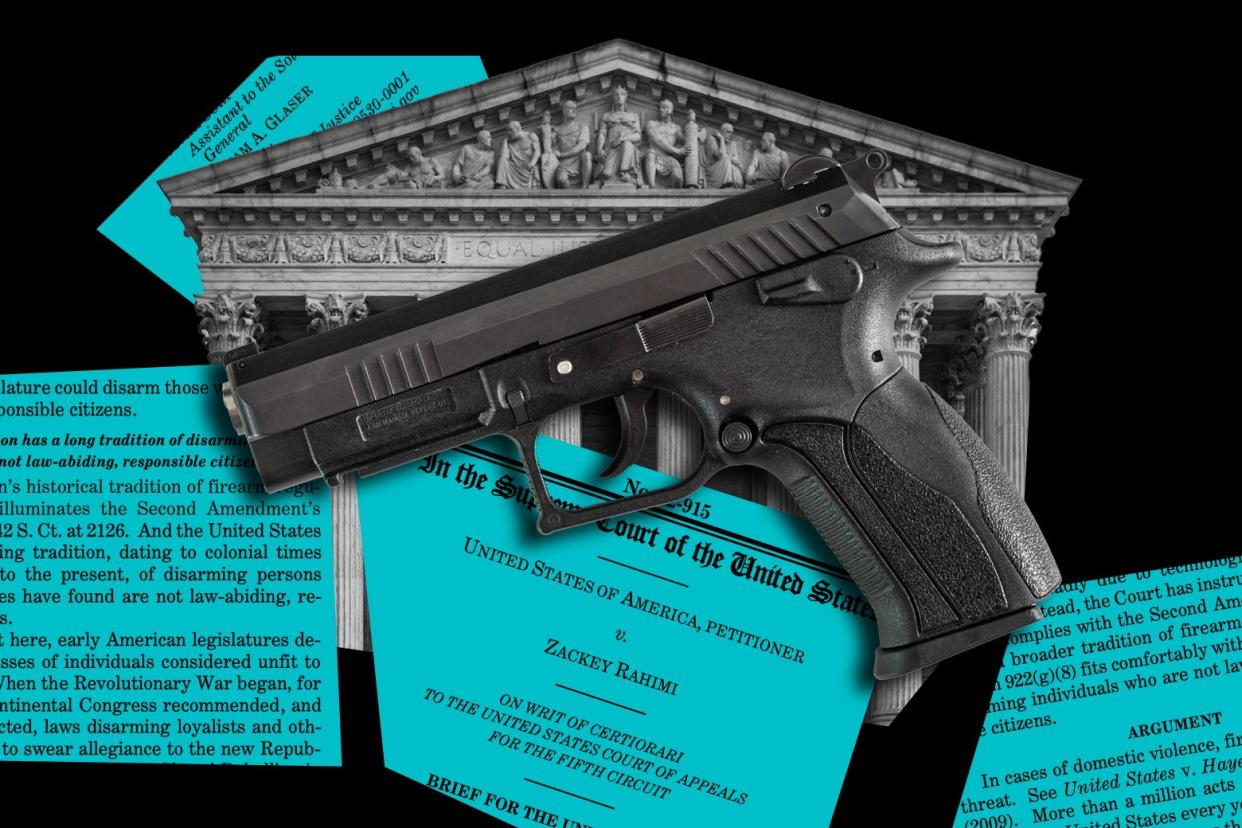

The Supreme Court’s new term opened this week with the extreme actions of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit looming over the entire term. Among the most alarming cases to arise is the first major gun-safety challenge that will test the court’s new Second Amendment doctrine, adopted last year. Hanging in the balance of United States v. Rahimi, and less remarked upon than the Second Amendment implications, is the modern movement against intimate partner violence. The verdict will bring home how the court treats contemporary progress against endemic violence with the lives of real people literally in the crosshairs.

Guns play an outsized role in the lethality of intimate partner violence. The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence reports that the presence of a firearm in the home increases the risk of homicide between 500 percent and 1,000 percent. While gender violence is a global epidemic, the Giffords Law Center estimates that women in the United States are 21 times more likely to die from guns than women in other high-income countries. Women of color are harmed at disproportionately higher rates. The consequences of firearms inside the home ripple outside immediately: In almost 50 percent of mass shootings, the perpetrator first shot an intimate partner or family member.

As an unrepentant abuser, Zackey Rahimi is a far cry from the model citizens recruited for prior gun-rights cases. After assaulting his girlfriend in a parking lot in 2019, Rahimi shot at a witness. The domestic violence protective order issued against him by a Texas state court in February 2020 prohibited the possession and use of firearms. But Rahimi subsequently participated in five separate shootings over a two-month period, leading to a search at his house where police discovered several firearms. Rahimi’s continued gun possession violated his protective order under the federal provision he’s now challenging.

Rahimi holds the upper hand walking into this argument. While the 5th Circuit initially affirmed Rahimi’s conviction, the court reversed course following the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in NYSRPA v. Bruen, which eliminated gun regulations that states cannot justify as “consistent with the Nation’s historical traditions.” Under Bruen, restraining orders have no historical analogue in the 5th Circuit’s eyes.

The thing is: Of course they don’t. The 5th Circuit is not wrong under the standard articulated in Bruen. In the founding era of the country, (married) women found neither protection nor recognition under the law. While rape was criminalized under early American legal codes, physical violence within the home was sanctioned through the doctrine of chastisement, under which husbands could inflict “moderate correction” to their wives.

As both the temperance and suffrage movements gained ground, attitudes toward physical violence began to shift. Alabama and Massachusetts led the way in 1871, criminalizing assaults by husbands against their wives. By the turn of the 20th century, the doctrine of chastisement had been largely repudiated. Yet the end of the chastisement doctrine did not stem abuse in the home. As Yale Scholar Reva Siegel has written, courts instead turned a blind eye to domestic violence in deference to the private sphere.

It wasn’t until the so-called battered women’s movement that feminist and queer activists began to break down a legal system that had long provided express, and then tacit, permission for men to abuse their wives. Advocates accomplished this by creating the means for people to escape violence in the home rather than seeking to solely punish men. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, states eased the availability of divorce through the introduction of no-fault grounds and opened shelters for people fleeing intimate partner violence. Activist Del Martin’s landmark book Battered Wives, which exposed the scale of domestic violence in the United States, was published in 1976, five years after the first shelter opened in Phoenix, Arizona.

The landmark Violence Against Women Act then enshrined protections into federal law in 1994, prohibiting abusers subject to domestic violence protective orders and felonies from possessing firearms. Two years later, Congress passed the Lautenberg Amendment to the Gun Control Act of 1968, which extended this protection to domestic violence misdemeanors (e.g., assault or battery), and applied the law’s provisions retroactively to include crimes committed prior to its enactment.

As Kaitlin Sidorsky and Wendy Schiller have catalogued, 28 states have passed domestic violence firearm laws since the passage of VAWA, while almost every one of those states also requires abusers to relinquish their guns. Forty states have passed the most minimal protection by prohibiting concealed carry permits for a domestic violence or stalking conviction or a domestic violence protective order.

The significant changes to American society from its “historical traditions” of misogyny and racism have yielded critical results. States with domestic violence firearm laws curb intimate partner homicide by up to 14 percent. Since federal law does not require background checks for all gun sales, domestic violence firearm laws play an important role in curbing access to firearms from people who have generally proven themselves to be dangerous. After felony convictions, the prohibitions of VAWA have created some of the most effective gun control in a country otherwise incapable of removing guns from people’s hands.

If the court adheres to a rigid interpretation of Bruen’s new test and eliminates domestic violence firearm laws, it will erase one of the biggest legacies of the modern history of the movement against intimate partner violence. Such a result would not be overly surprising, given the court’s recent approach in cases on gender violence. In the 2000 case United States v. Morrison, the court rejected the argument that gender violence has an economic impact despite painstakingly collected data that not only proves the contrary but formed the very heart of VAWA itself. Over 20 years later, the court also rejected information about the economic gains of reproductive autonomy when it overturned Roe v. Wade.

The conservative wing of the court may use Rahimi to double down on the test established in Bruen or retreat in the gaze of intense public backlash and scrutiny. No matter the outcome, Rahimi represents the continued clash between the reality of women’s lives and the court’s myopic and exclusionary vision of our nation’s past.