Tale of two streets: Renaming movement finds some Southern streets divided

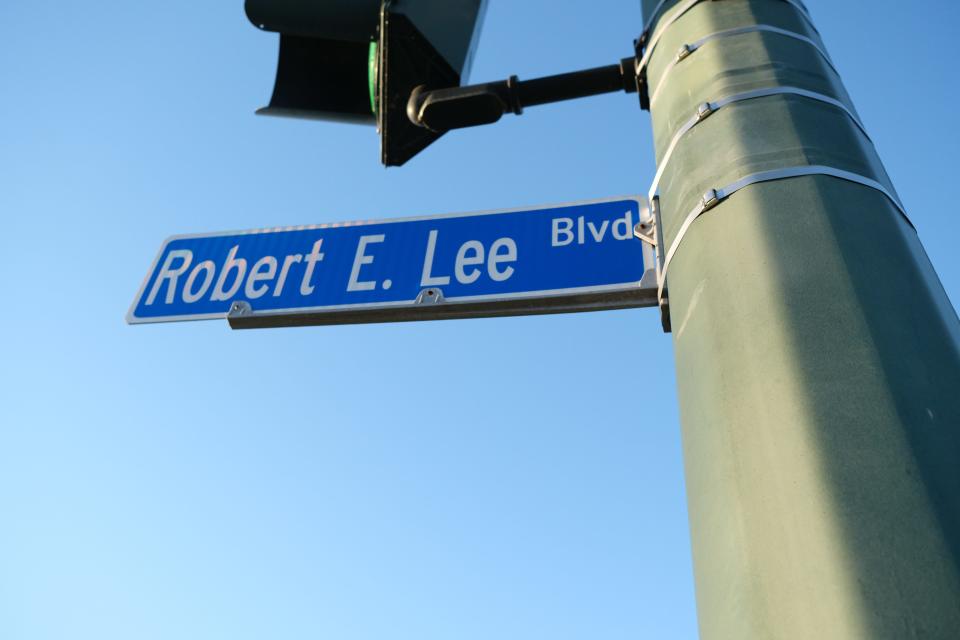

For the last decade of his life, acclaimed New Orleans musician Allen Toussaint lived on Robert E. Lee Boulevard.

His blue Rolls Royce Corniche, as polished as one of his compositions, sat in the driveway of a house adorned with treble clefs.

Neighbors can still picture the mustachioed Toussaint languidly cruising the boulevard on weekends. His daughter, Alison Toussaint, said he’d stop when he heard music.

“If someone on the street was having a little soiree, he would park and get out and check out what was going on,” Alison Toussaint said. “And if he saw a piano anywhere, he was going to play.”

In 2020, the police killing of George Floyd and ensuing protests ignited a nationwide reckoning with longstanding symbols of racial oppression.

Late last year, Montgomery Mayor Steven Reed proposed renaming Jefferson Davis Avenue in honor of civil rights attorney Fred Gray, who grew up on that street. That touched off a complex, year-long renaming process that involved changing the rules that govern street renaming and ended with the City Council voting unanimously in favor of the name change despite an Alabama state law meant to protect Confederate monuments.

Like other Southern cities such as Montgomery, Memphis and Charlotte, New Orleans’ City Council responded to the events of summer 2020 by approving a commission to identify streets named for white supremacists and suggest alternatives.

After months of examining historical records, gathering public comments, and hosting mid-pandemic Zoom meetings with neighborhood groups, the New Orleans City Council Street Renaming Commission released its final report in March 2021 and recommended changes to three parks and 34 streets, including Robert E. Lee Boulevard.

When the commission recommended renaming the street for Toussaint, who died in 2015, historian Thomas Adams did not anticipate opposition to replacing the Confederate general with a celebrated Black musician.

“We were like, ‘This is going to be a layup,’ ” said Adams, who assisted the commission in its renaming research.

New street names: New Orleans commission suggests new names for 37 streets and parks

Instead, during the past year, the debate surrounding the renaming of Robert E. Lee Boulevard divided residents along the street after some in the Lakeview neighborhood — a predominantly white, more affluent section of the street — voiced opposition to naming the street for Toussaint.

The process also exposed lingering effects of bygone segregation policies and showed how complicated renaming a roadway can be as cities re-examine those who are memorialized on street signs.

On April 14, a month after the commission submitted its final recommendation to the City Council for approval, Alison Toussaint received a call from District D Councilman Jared Brossett. He told her there were rumblings that some residents wanted to split the street to omit the section that borders Lakeview, she said.

“There has been discussion of a split in the street, that Robert E. Lee would be named after my father in the Black section of Robert E Lee, not the entire street,” said Alison Toussaint, who still lives on the boulevard. “We don’t want a divided street named for our father.”

Robert E. Lee Boulevard divided

Robert E. Lee Boulevard runs parallel to the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain, traversing two city council districts and three neighborhoods: Lakeview in City Council District A to the west and the more diverse Lake Vista and Gentilly neighborhoods in District D to the east. Toussaint was no stranger in any of them.

Lakeview residents recall seeing Toussaint at the grocery store. Prior to moving into his Lake Vista home after Hurricane Katrina, he spent decades at his Sea-Saint music studio in Gentilly cutting tracks with artists like Patti Labelle and Elvis Costello.

“We were really wanting to make sure that the (recommended) people had a connection as much as possible to the street,” Adams said. “The connections were clear. He was not a controversial person.”

Robert E. Lee Boulevard had been divided before in more ways than one.

Prior to it being named for the Confederate general in 1923 — the street was one of 104 citywide street name changes that year, according to New Orleans Item archives — the 3-mile stretch through Lake Vista and Gentilly was called Hibernia Street. The mile-long western end in Lakeview was Adams Street.

Lakeview had been swampland until it was drained and developed to create valuable lakefront properties around the turn of the 20th century. A 1907 New Orleans Land Company brochure called New Orleans “The New York of the South” and compared the growth of Lakeview to that of Manhattan Island.

The new subdivision was also originally redlined.

“A stipulation in the original title bars forever negroes as residents,” advertises the marketing materials in the same paragraph that boasts of alleyways residents could use for back-door deliveries.

'This is not just about symbols': America's reckoning over Confederate monuments

Toussaint’s connection to residents up and down the boulevard seemed to make him a unifying selection in an area where the impact of segregationist planning concepts can still be seen. In a 2018 report analyzing the history of segregation in the city, the New Orleans Data Center found that residents of color increase — and property values decrease — as the street stretches eastward from Lakeview into Gentilly.

But Derek Alderman, a University of Tennessee cultural geographer who has studied the history of street name changes, said most renaming conversations involve two conflicting factors: historical context versus personal memories.

“Streets are monuments used every day,” Alderman said. “They become part of a neighborhood’s identity. But they also become part of the larger symbolic text of the city.”

‘The mood has become one of hate’

The differences in opinion regarding the renaming can be heard as you move between the neighborhoods.

In Lake Vista, 45-year-old LaRose Taylor put it succinctly.

“They need to change the name,” said Taylor, a Black woman. “He owned slaves.”

Further west toward Toussaint’s old house, a woman who asked to only be identified as Heather stood on her porch. Next to her was a pile of Amazon packages, each shipping label stamped with the name of the Confederate general.

The City Council had appointed the renaming commission in the summer of 2020, a few months before Heather moved to the home. A year later, she said she had expected it to be changed by now.

“It’s humiliating to tell friends that this is my address,” Heather said. “We want it to be named for Allen Toussaint. Then we moved here and heard that some people didn’t want that.”

Karl Connor, chairman of the commission, said there was “very little pushback” from Lakeview residents about removing Lee’s name.

Still, residents on that side of the boulevard offered reasons why it shouldn’t bear Toussaint’s name even as they praised him.

Russell McCoy, a 64-year-old resident of the boulevard, called Toussaint an “ambassador of the city” but added, “Allen Toussaint Boulevard, people are going to misspell that a lot, you know? Who’s going to get my mail?”

McCoy suggested Lake Boulevard as a better choice.

“I don’t think you necessarily have to rename streets for people,” McCoy said. “I don’t have a problem with naming it for people, but they’re structuring it some type of way.”

At virtual meetings with the commission, others offered similarly neutral names such as Lakeshore Boulevard. Former Lt. Gov. Jimmy Fitzmorris was another option. Many liked the idea of naming the street for Pete Fountain, another musician who lived in the neighborhood.

“Nobody outright said, ‘We don't want a Black person's name on the street,’” Connor said. “But, what we could not do is inadvertently support something that seemed that way.”

Longtime residents such as Val Cupit, a board member of the Lakeview Civic Improvement Association who has lived in Lakeview just off Robert E. Lee Boulevard since 1954, said the neighborhood felt dismissed.

When asked about the difference between naming a street for Toussaint or Fountain, who was white, Cupit said, “Pete Fountain lived over here. My daddy grew up with him. Allen Toussaint lived closer to UNO.”

“So you could name one half of the street for Pete Fountain and the other half for Allen Toussaint,” she added.

Attempts to interview Councilman Giarrusso, who represents District A, were unsuccessful. But emails between him and his constituents obtained by The American South show how quickly tension entered the process.

In June 2020, weeks before the City Council selected commission members, Giarrusso received an email from someone suggesting Lake Town Boulevard. In response, Giarrusso proposed naming it Mother Cabrini Way after the first ordained saint of New Orleans.

“Would that be offensive to others of different religious beliefs?” the emailer responded. “...People’s Names just insight (sic) opposition from somewhere no matter who is chosen.”

A month later, Giarrusso seemed to have moved toward a similar view.

A constituent emailed that “A lot has happened since we spoke. The mood has become one of hate…” Giarrusso replied that he was “starting to get more hesitant about naming streets after people” because “whatever name is picked will not satisfy everyone.”

“If you pick Fitzmorris, then the music people will be unhappy. If you pick Fountain or Toussaint, then you frustrate the Fitzmorris backers,” Giarrusso wrote. “It is kinda hard to argue with returning to one of its original names (Adams or Hibernia), though there will be frustration no matter what happens.”

The commission did not have an explicit goal to name streets for Black New Orleanians, Connor said. Proposed street names in other parts of the city included white civil rights lawyer John "Jack" Nelson and Charles McKenna, an Irish immigrant who was one of thousands to die while building the New Basin Canal in Lakeview.

Still, the commission wanted to tell a different story of New Orleans.

“None of the things that the folks in the neighborhood suggested passed for us,” Connor said. “Mostly it was because we were trying hard not to look like we were supporting two New Orleanses where folks in a more affluent part got to do what they wanted and name a street after another white male or some inanimate object.”

Throughout the process, Councilman Giarrusso defended renaming Robert E. Lee to those who spoke against it. But in April of this year, a month after the commission submitted its final recommendations, he felt that the commission had not done “the legwork” to build a consensus.

“If something is so innocuous, why not find either common ground with a different name or, as a fallback, splitting the street?” he wrote. “...Either one of those approaches makes more sense than dictating to people.”

The ‘danger’ of splitting streets

The modern history of street renaming as a form of racial reckoning can be traced back to Chicago, which in 1968, approved the first street to be named after Martin Luther King Jr.

An initial proposal would have put the street in the city’s central business district. Instead, then-Mayor Richard Daley proposed an alternate resolution and King’s name was instead placed in Chicago’s predominantly Black south side, Alderman said.

Since then, Alderman said splitting streets named for King along racial boundaries “happens a great deal.”

“They can get the largely African-American part of that street to rename. And because of white opposition, they can't rename the rest of the street,” Alderman said.

In New Orleans, part of Melpomene Street that ran through majority Black neighborhoods was renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in 1977. Melpomene Street continued in the majority white Garden District.

“The danger of splitting streets is that cities can operate as, ‘Well this is white memory and this is Black memory,’” Alderman said. “If you restrict only one part of the street for a Black historical figure, then you’re suggesting that figure’s historical importance is somehow restricted and that we, in a Southern society, cannot cross racial boundaries.”

Connor said he does not support naming only part of Robert E. Lee Boulevard for Allen Toussaint.

“Cutting the street in two would be antithetical to who he was,” Connor said. “It’s just not something I could support as the chair.”

For some in Lakeview, the thought that splitting the street could be controversial was absent from their discussion.

Jack Jelenko, another resident who liked the idea of splitting the street between Fountain and Toussaint, said it made geographic sense since Fountain lived closer. When asked about the optics of naming a whiter section of a street for a white musician, however, he paused.

“To be honest, until you just said that, it never even entered my mind,” Jelenko said. “That’s definitely a con.”

Still, some longtime residents felt the decision should rest with the community.

“Who would we offend?” Cupit said. “We’d offend ignorant people from up north who don’t know squat about New Orleans. I love Allen Toussaint. I grieve him. I wish I could see him again. I have a lot of Black friends. I have no problem with skin color. I have a problem with bullies, and that’s what this is.”

The road to racial reckoning

New Orleans is not the only city wrestling with the complexities of street renaming. Southern cities such as Montgomery, Memphis and Charlotte also formed street renaming commissions in 2020.

When it comes to questions about what names should replace them, who gets to decide, and who the changes are intended for, there is no standardized road map.

In Montgomery, a city ordinance required property owners to approve a street name change proposed for Jefferson Davis Avenue last December. After many property owners failed to respond, the city council voted to alter the ordinance to make non-responses count as “yes” votes. That process ended in October with the city taking down the former Confederate leader's name and replacing with with Fred D. Gray Avenue.

Gray was an attorney for several of the Civil Rights era’s most prominent leaders and still practices law with his Tuskegee-based firm, with an office in Montgomery. Reed said Gray’s connection with the community where he grew up led the 90-year-old attorney to suggest the street renaming as an appropriate way to honor his legacy.

“He didn’t ask for the municipal courthouse to be named in his honor,” Reed said at the October dedication. “He didn’t ask for the law library to be named in his honor. He asked for this street because of what it means.”

The street intersects with another road named in honor of one of Gray's clients during the civil rights movement, Rosa Parks.

In Charlotte, the renaming of Jefferson Davis Street was put to a popular vote among residents and property owners who opted for a neutral route, selecting Druid Hills Way with 55% of the vote.

“Many cities suggest that the people who live and own property on a particular street should have the predominant word,” Alderman said. “This struggle is not just about who wants to be identified with what name. It's about giving groups of historically marginalized people the opportunity to claim a right to how that city talks about its past.”

Street names serve a practical purpose. They adorn business cards and letterheads. They’re uttered on 911 calls in moments of crisis. In short, they provide location. They tell you where you are.

As 2021 draws to a close, it’s unclear where New Orleans is in terms of renaming Robert E. Lee Boulevard and the 36 other streets and parks recommended in the report.

The name changes have yet to be brought to a vote by the City Council.

In the months since the commission’s final report, the city has grappled with the Delta variant and Hurricane Ida. November is also election month for the city councilmembers, which Connor said has “dictated the pace at which we're seeing changes implemented.”

For now, the street sign bearing the name of Robert E. Lee will continue to hang over the boulevard.

"Street names don't just develop randomly," Alderman said. "They get made actively. And so behind every street name is a story of how you reconcile."

News tips? Questions? Call reporter Andrew Yawn at 985-285-7689 or email him at [email protected]. Montgomery Advertiser reporter Brad Harper contributed to this report.

This article originally appeared on Montgomery Advertiser: Street renaming movement finds one New Orleans street divided