The threat of 'superbugs' and infections that can't be treated

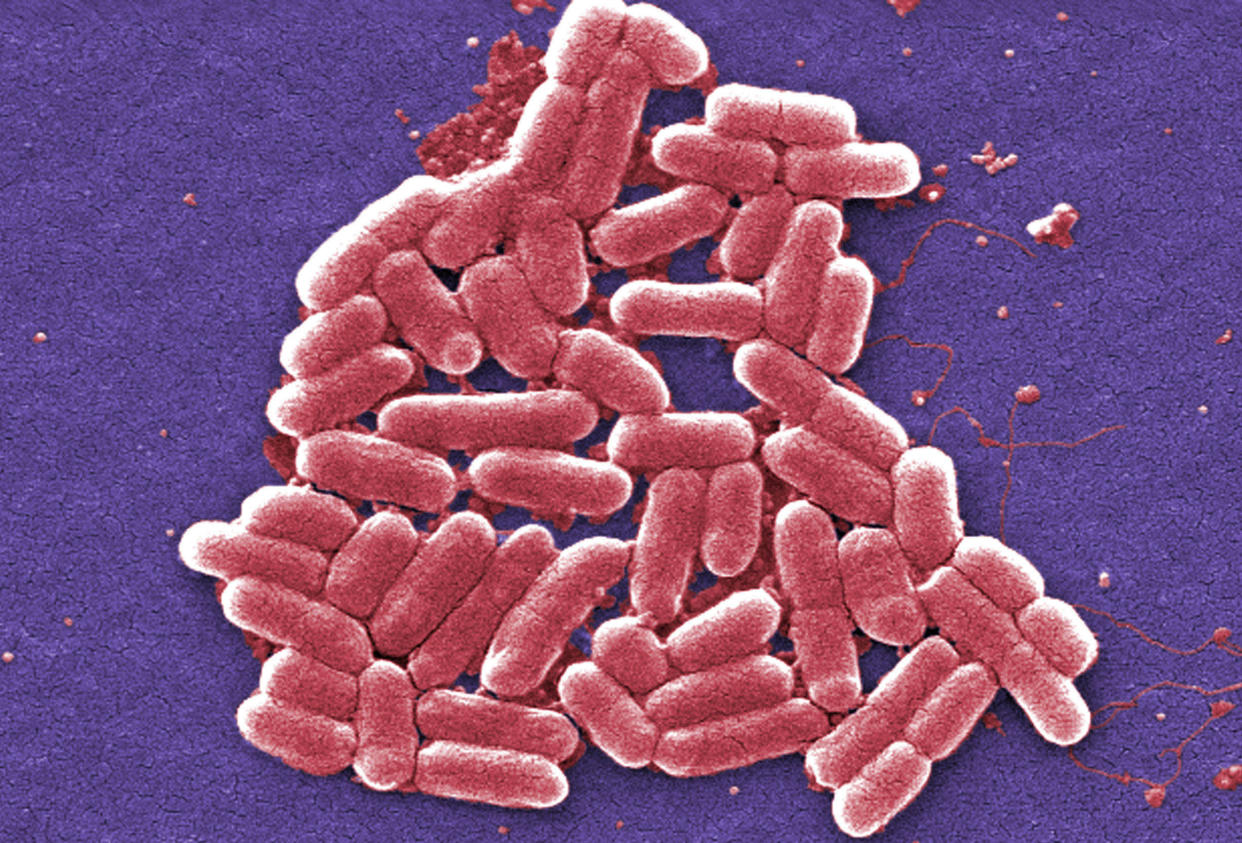

“Every time we think we’ve gotten ahead of the bugs, they come back stronger and fitter,” said Ramanan Laxminarayan, director of the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy (CDDEP). It is the ability to mutate that has given rise to “superbugs” that resist some — or, increasingly, all — of the antibiotics that were hailed as miracle drugs in the last century, creating one of the biggest threats to global health, food security and development today, according to the World Health Organization.

For years, experts have warned against the overuse of antibiotics in livestock and fish farming, which stave off infections in animals in crowded living conditions and also help animals gain weight faster, making them ready for slaughter sooner. The phenomenon, along with over- and unnecessary prescription of antibiotics and a lack of a new class of antibiotic drugs, have promoted the growth of resistant bacteria. As susceptible microbes are killed off, the resistant survivors thrive and multiply. Today, a growing number of bacterial infections, including pneumonia, tuberculosis and gonorrhea, are more difficult to treat because of such resistance — at least 2 million people become infected with bacteria resistant to antibiotics and at least 23,000 people die each year in the U.S. as a direct result of such infections, according to the CDC.

“This scale-up in antibiotics, primarily as a substitute for good nutrition and hygiene in livestock production, is simply unsustainable and will be devastating to efforts to conserve the effectiveness of our current antibiotics,” said Laxminarayan, the senior author of a new study focusing on antibiotic use in livestock. “We already face a crisis, but continuing to use medically important antibiotics for growth promotion in animals is like pouring oil on a fire.”

“Over the last 10 to 15 years, resistance has grown from under 2 to 3 percent to between 30 to 80 percent [encountered in humans globally],” Laxminarayan told Yahoo News. “That’s a big deal. We now have patients who have completely untreatable infections in every part of the world.”

The new research from the CDDEP analyzed and described a comprehensive strategy for preserving antibiotic effectiveness by reducing antibiotic use in farm animals up to 80 percent globally by 2030.

To reduce antibiotic use in livestock, the authors of the study, which was published in Science, suggested three interventions: regulations on the use of antibiotics in farm animals; limiting meat intake; and the imposition of taxes on veterinary antibiotics.

“One can safely predict that the bugs will outsmart us every time,” said Laxminarayan.

At last year’s U.N. General Assembly, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) was of top importance. Dr. Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, called it a “major global threat.” At this year’s summit, the WHO reinforced its intention to combat superbugs.

“This is only the fourth time a health issue has been taken up by the U.N. General Assembly — the others were HIV, noncommunicable diseases and Ebola — so the serious nature of AMR’s effects should not be taken lightly,” said Dr. Dean Hart, a professor at the Columbia University School of Medicine.

As the largest consumer of veterinary antimicrobials in the world, China needs to take a leading role in combating AMR, the researchers said. The country recently promulgated new nutritional guidelines recommending 40 to 70 grams — less than 2.5 ounces — of meat per day, which is about half the current consumption level in the country. China is also phasing out certain drugs in livestock that are still used in Europe. If followed, the measure could have a substantial impact on reducing antimicrobial consumption and, in turn, resistance. The U.S. has introduced a voluntary ban on the use of antibiotics for growth purposes. McDonald’s announced in August a 10-year plan to phase out antibiotics in its poultry production chain beginning in 2018.

The U.S. also has seen a large shift to organic consumption based on consumers’ greater awareness of the potential dangers of antimicrobial resistance. Still, demand for organic products is a luxury — “most of the world’s population simply can’t afford the benefits of eating strictly organic products, especially in Third World countries,” said Hart.

When compared with other developed nations, Denmark and Germany are quite conservative when it comes to using antibiotics — and results show that those populations have lower levels of AMR, said Hart. Interestingly, the U.S. shows relatively moderate levels of resistance even though the population uses antibiotics heavily.

Of note, the quality of a country’s health care system also seems to have a direct relation to antibiotic resistance levels, said Hart. EU countries have very high standards, but antibiotic use is too high. Venezuela’s health care system is far less robust; this means antibiotics are far scarcer, and AMR is relatively lower.

Hart also pointed to pharmaceutical manufacturers as obstacles in the fight against AMR. “We are a country that buys drugs, and a lot of them, at much higher prices than the rest of the world,” he said. “The antibiotic market is huge business for these companies, and the push to develop the new ‘superdrugs’ is something that affects their bottom line. While treatment with older forms of antibiotics can often be effective and serve the greater good of humanity, the inclination of doctors is almost always going to be to use the latest and greatest new medicine available.”

Hart argued that awareness is the most important factor: Doctors should be advised to first treat bacterial infections with older forms of antibiotics that have a proven track record of being effective. Patients should understand that antibiotics have zero effect on viral infections such as the flu or the common cold. “The next super-infection can be just around the corner, and we must be prepared.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: