Trump isn't the first president to politicize the census

A simple count of everyone in the country. What could be so hard about that?

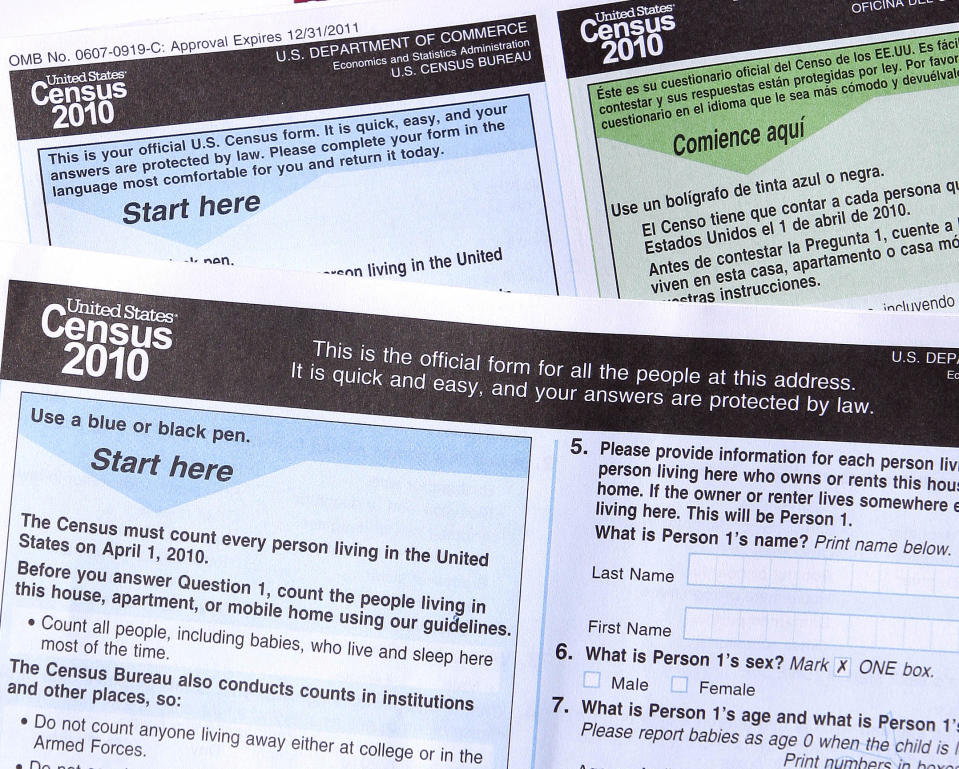

In the 23 times that count has been done in the United States since the Constitution first required it in 1790, it’s become clear that there is almost nothing simple about the decennial census. The announcement this week that at least a dozen states would sue the Trump administration for adding a question about citizenship status to the 2020 census is but the most recent fight over what seems like should be a straightforward mathematical enumeration, but has almost always been an emotional and political one.

“Of course it’s political, it is the underpinning of the entire political system,” says Margo Anderson, distinguished professor of history and urban studies at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee and author of The American Census: A Social History. “It is always controversial.”

But if the fact that the census regularly results in a political fight is news to you, Anderson is not surprised. “Issues of race and region, growth and decline, equity and justice, have been fought out in census politics over the centuries,” she writes in the introduction to her book, “though because decades may pass between flare-ups of particular issues, the participants are often unaware of relevant earlier debate.”

Mandated by Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution, the census decides the population of each state, which in turn determines how much representation that state gets in the House of Representatives, how many votes each state has in the Electoral College, and what percentage of federal funds a state receives. A change in a state’s population, therefore, results directly in a gain or loss in that state’s political and economic clout.

In fact, the first political tussle over the census came during the writing of Article 1 in 1789. Southerners wanted slaves counted in their tally, as it would increase their numbers and their power, while Northerners wanted the opposite. The compromise was that slaves counted as 3/5 of a person, a choice that would haunt the nation well beyond the Civil War.

The Constitution only requires a population count, or “enumeration.” Which questions are asked during that count are decided by the census bureau, and over time form a snapshot of what issues felt important to the nation every 10 years. “The questions change with whatever is salient,” Anderson says.

In 1920, for instance, it felt time to take out the question about whether each household member had served in the Union or Confederate armed forces. That same year, questions were added that asked each U.S. resident when they naturalized, as well as for their own mother tongue and those of their parents.

By 1940, there were questions trying to gauge the impact of the Depression, asking about the need for housing, employment and unemployment, income and how often and where a family had moved in search of work.

In 2010, same-sex married couples were allowed for the first time to mark their spouse as “husband” or “wife” on a census form, and a box for “unmarried partner” was also available.

Sometimes the flare-ups over the census are caused by doubt about the results. Both George Washington and Alexander Hamilton thought the first census — which found that 3.9 million people lived in the young nation — was an undercount.

In 1840, an argument erupted over the accuracy of an apparent spike in “insanity” among the nation’s freed black population — at a rate of 1 in 162 in the North and 1 in 1,558 in the South. Advocates for slavery seized on those statistics to show that slaves went insane when freed; abolitionists countered that the data were simply wrong, the result of a confusing design of the census form that allowed elderly white members of a household to be counted in the column for “colored” and for some of those “insane” blacks to be attributed to families that had no black members. “The historical consensus is that the data were in fact wrong,” Anderson says.

In 1930, the fight was over unemployment, since the count took place so soon after the stock market crash. By the time the data was processed, the jobless figure was attacked as being too low by legislators who had hoped for higher numbers to justify a larger federal response. Congress in fact authorized a special 1931 census just to measure unemployment, and that number was much higher than it had been the year before.

Miscounts did not end with the modern era and its introduction of computer questionnaires in place of handwritten tallies by door-to-door enumerators. In 1990, for instance, 10 million Americans were somehow “lost” and 6 million were apparently counted twice. As most of those lived in poverty, the states where they resided could not qualify for the federal funds that might otherwise have been available for services.

Other controversies took place before the counting even began. In response to the 1990 miscount, the Clinton administration announced 10 years later that it would use data sampling to estimate the population rather than counting each individual. Republicans feared that this would result in an increased representation of minority groups, which would in turn result in election districts more favorable to Democrats. Newt Gingrich sued the Census Bureau, and a federal court struck down the sampling plan.

And now there is the uproar over citizenship. The question has appeared periodically on census questionnaires over the years, but has not been included since 1950. The Department of Justice, which in January of this year asked for it to be added again, says that in order to enforce the Voting Rights Act, there must be a count of citizens who are old enough to vote. Those opposed to the addition argue that it will increase a trend toward individuals refusing to reply to all census questions for fear of exposing private information. A September 2017 memo written by bureau staff described “a recent increase in respondents spontaneously expressing concerns about confidentiality” in some pretest studies on the upcoming form, creating a “new phenomenon … particularly among immigrant respondents.”

If response rates are in fact depressed, history shows, the eventual count will be inaccurate, and in this case would increase the power of states with fewer undocumented immigrants.

Rather than remain a dry argument over the efficacy of sampling a wary population, however, the debate over the citizenship question has taken on some of the same emotional tones common to census arguments throughout history.

Since the Commerce Department confirmed Monday night that respondents in 2020 would be asked if they are citizens, state attorneys general began to fight back. Eric Schneiderman of New York called it a “reckless decision to suddenly abandon nearly 70 years of practice,” and warned the change would “create an environment of fear and distrust in immigrant communities that would make impossible both an accurate census and the fair distribution of federal tax dollars.”

The Trump/Pence campaign, in turn, sent out an email blast on Wednesday afternoon asking supporters to sign a petition to “Defend the President: 2020 Census Questions.”

“President Trump has officially mandated that the 2020 United States Census ask people living in America whether or not they are citizens,” the letter read. “And the sanctuary state of California is now SUING the Trump Administration to stop this commonsense order.

“We cannot let a few Hollywood special interests speak for the rest of our country,” it concluded. “It’s time to fight back. It’s time to once again reclaim our voice in America.”

(Cover thumbnail photo Illustration: Yahoo News; photos: AP)

Read more from Yahoo News: