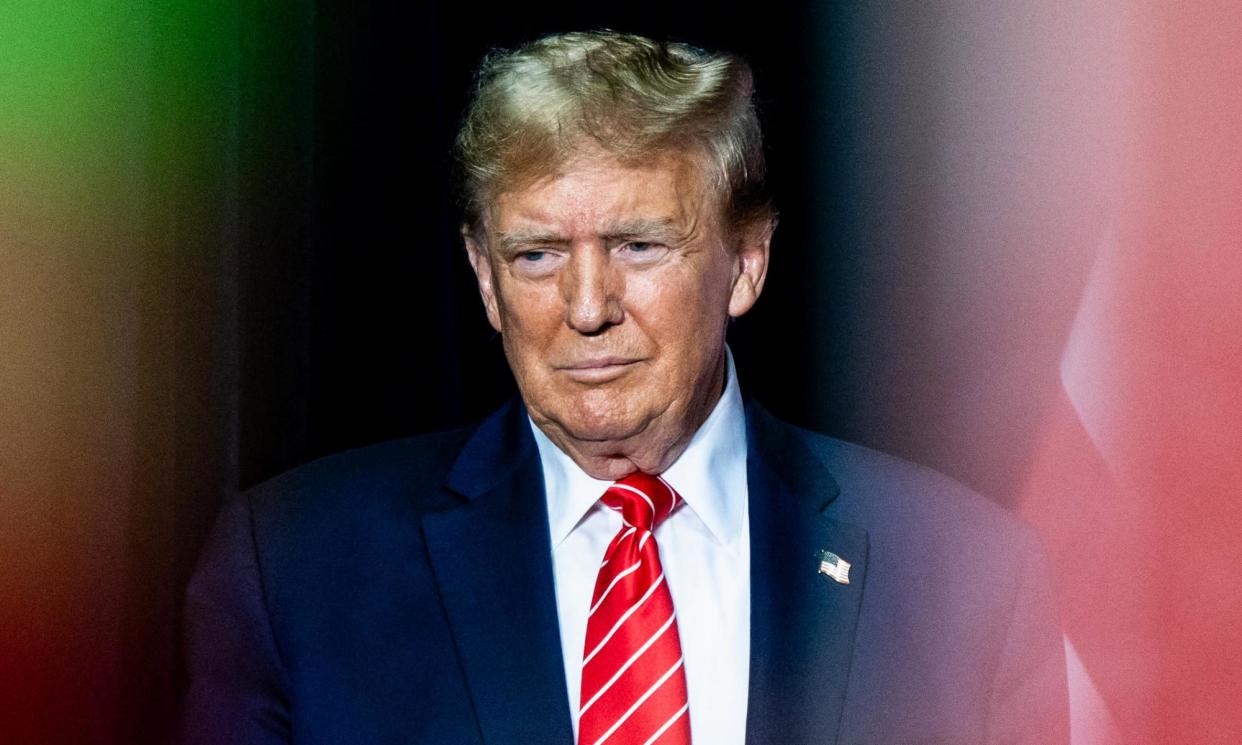

Trump lawyers urge US supreme court to dismiss election interference case

Lawyers for Donald Trump urged the US supreme court to find that presidents have absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for official acts they take in office and, therefore, dismiss the federal criminal case against Trump over his efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election.

The arguments from Trump came in a brief submitted to the court Tuesday before oral arguments on 25 April, when the justices will consider whether and to what extent a former president has absolute immunity from prosecution for conduct alleged to involve official acts.

Related: The US supreme court could still swing the election for Trump | Lawrence Douglas

“The court should restore the tradition,” Trump’s brief said, “and neutralize one of the greatest threats to the president’s separate power, a bedrock of our republic, in our nation’s history. The court should uphold the president’s immunity from criminal prosecution for official acts.”

In the 67-page filing, Trump re-advanced the argument that he enjoyed absolute immunity from prosecution because the conduct charged by the special counsel Jack Smith over his plot to stop the transfer of power fell within the “outer perimeter” of his duties as president.

The filing contended that all of Trump’s attempts to reverse his 2020 election defeat, from pressuring his vice-president, Mike Pence, to stop the 6 January 2021 certification to organizing fake slates of electors, were protected activity.

If the supreme court were to agree with Trump that he enjoyed absolute immunity from prosecution based on his sweeping interpretation of un-reviewable presidential power, the brief argued, it should also dismiss the indictment in its entirety.

The arguments from Trump doubled down on positions his lawyers took when they argued before the US district judge Tanya Chutkan, who denied Trump’s attempts to dismiss on immunity grounds last year, and before the US court of appeals for the DC circuit, which also denied his claim.

Trump reiterated that presidents can only be prosecuted if they have been convicted in a Senate impeachment trial, pointing to language in the US constitution that a “party convicted” by the Senate “shall nevertheless be liable and subject to indictment, trial, judgment and punishment”.

The argument received a cold reception at the DC circuit, where the three-judge panel assigned to hear the appeal questioned incredulously whether that meant a president could officially order the US Navy’s Seal Team Six to assassinate a political rival and face no repercussions.

But Trump’s brief claimed that without the guarantee of absolute immunity, the threat of potential prosecution would prevent future presidents from feeling free to take decisive action without being second-guessed by prosecutors later on.

“Every future president will face de facto blackmail and extortion while in office,” it said. “The threat of future prosecution and imprisonment would become a political cudgel to influence the most sensitive and controversial presidential decisions.”

If the court were to decide that presidential immunity did apply to Trump but on a charge-by-charge approach, Trump’s brief said, it should return the indictment back to the lower courts with instructions to review each alleged illegal action and determine whether it should be struck out.

Trump’s lawyers settled on advancing the immunity claim last October in large part because it is what is known as an interlocutory appeal – an appeal that can be litigated pre-trial – and one that crucially put the case on hold while it was resolved.

Putting the case on hold was important because Trump’s overarching strategy has been to seek delay, ideally even beyond the election, in the hopes that winning a second presidency could enable him to pardon himself or allow him to install a loyal attorney general who would drop the charges.

The involvement of the supreme court now means the case remains frozen until the justices issue a ruling. And even if the court rules against Trump, the case may not be ready for trial until late into the summer or beyond.

The reason that Trump will not go to trial as soon as the supreme court rules is because Trump is technically entitled to the “defense preparation time” that he had remaining when he filed his first appeal to the DC circuit on 8 December, which triggered the stay.

Trump has 87 days remaining from that period, calculated by finding the difference between the original 4 March trial date and 8 December. The earliest that Trump could go to trial in Washington, as a result, is by adding 87 days to the date of the supreme court’s final decision.

With oral arguments set for April, a ruling might not be handed down until May. Alternatively, in the worst-case scenario for the special counsel, the supreme court could wait until the end of its current term in July, which could mean the trial might be delayed until late September at the earliest.