Ukraine scandal gives new life to Warren's pledge to keep politics — and campaign donors — out of foreign affairs

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

The House impeachment inquiry into President Trump’s dealings with Ukraine has, as one consequence, called attention to the conflict between career foreign service professionals and Trump’s political appointees to ambassadorships and other key positions.

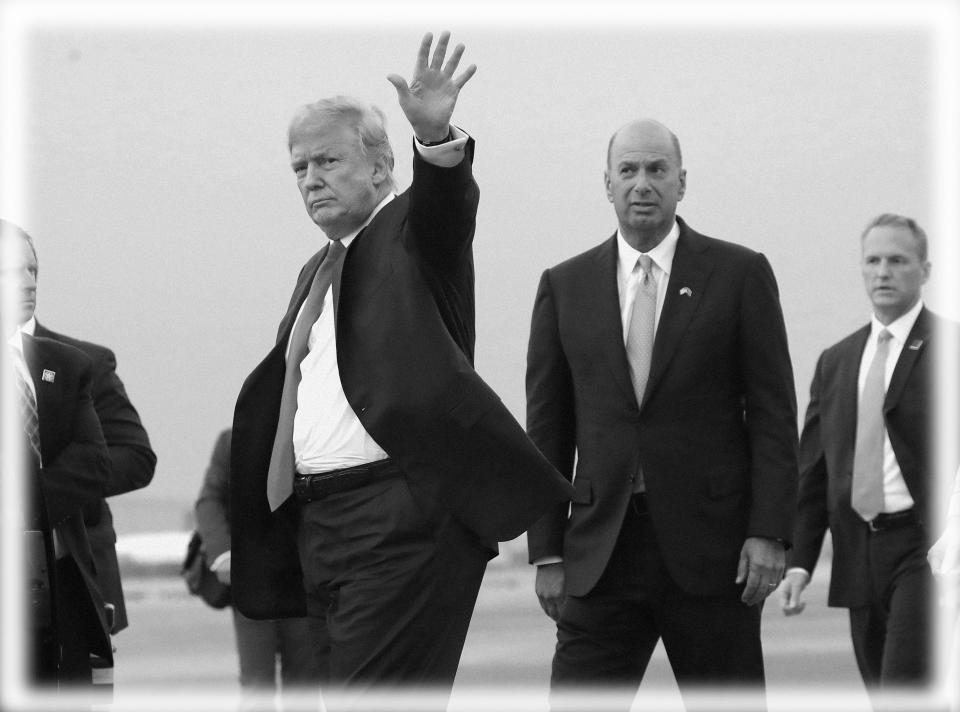

Gordon Sondland, the United States ambassador to the European Union, made headlines Tuesday for his last-minute refusal, on orders from the State Department, to testify about his role in Trump’s efforts to coerce Ukraine to investigate former Vice President Joe Biden.

A GOP donor and hotel magnate with no prior diplomatic experience, Sondland was appointed to his current post by Trump in 2017. How he became embroiled in the Trump administration’s decision to withhold U.S. military aid from Ukraine as well as the president’s attempts to convince Ukraine’s president investigate Biden remains unclear. While a priority trading partner with the EU, Ukraine itself is not a member state.

Sondland’s appointment came one year after he donated $1 million to Trump’s inaugural fund. Text messages made public last week illuminated his role in pressuring Ukraine’s government to launch an investigation into Biden and to promote Trump talking points that the president had not sought a quid pro quo linking the release of military aid for dirt on one of Trump’s leading political rivals.

Apart from Sondland’s personal qualifications and his alleged willingness to put loyalty to Trump ahead of U.S. policy interests, the imbroglio illustrates what critics say is a worrisome decline in the morale of American foreign service professionals, and a waning of American “soft power” around the world. As Trump’s first secretary of defense, Jim Mattis, famously put it, “If you don’t fully fund the State Department, then I need to buy more ammunition.”

Awarding political patronage with a plum diplomatic post is a time-honored tradition in American politics.

President Trump’s picks for ambassadorships, however, have drawn scrutiny, with critics alleging they were appointed simply because they donated large sums of money. In fact, roughly half of those Trump has nominated to serve as ambassadors have been political appointees, NBC News reported. Doug Manchester, for instance, is a billionaire real estate developer who became ambassador to the Bahamas after donating $1 million to Trump’s inauguration committee. Trump’s pick to be the ambassador to the U.N., succeeding Nikki Haley, is longtime GOP donor Kelly Craft, who donated over $260,000 to Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, while her husband kicked in roughly $1 million to the president’s inaugural committee. John Rakolta Jr., the ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, is another Republican megadonor — giving $250,000 to Trump’s inaugural committee — and was approved for his post despite holding no prior diplomatic experience.

But that was also true of his immediate predecessors. Former President Barack Obama named 31 campaign donors as ambassadors during his second term in office, most of them stationed in Western European nations or places like Canada or New Zealand, the Center for Public Integrity reported. Career diplomats represented the U.S. in less glamorous places such as Pakistan, El Salvador or Somalia — where, apart from the relative hardships of such postings, their expertise was actually far more important. Being ambassador to France, on the other hand, is more about knowing which fork to use than the nuances of American policy toward the EU.

A study by Scholars & Rogues found that 36 percent of former President George W. Bush’s nominees for ambassadorships were to “non-career appointees.” Twenty-four of those were so-called Pioneers and Rangers, donors who gave between $100,000 and $200,000 to Bush’s 2000 and 2004 presidential campaigns, Mother Jones reported.

Seizing Sondland’s decision to skip his scheduled testimony, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., took the opportunity Tuesday to tout her plan, originally announced in June, to keep presidents from awarding wealthy donors with ambassadorships.

Warren’s plan to root out corruption among the diplomatic corps begins with a proposal to double the size of the foreign service. “Too few diplomats means missed opportunities to make important connections and develop a better understanding of foreign countries,” Warren says on her website. To recruit and train qualified diplomats, she would, among other things, double the size of the Peace Corps so as to expose “young people to the world and [create] a direct employment pipeline to future government service.” She would also seek to make sure that those who rise in the diplomatic ranks are properly qualified. “We will require a broadening professional development experience — a graduate degree, interagency assignment, or cross-cone deployment — before promotion to the senior diplomatic ranks,” Warren says on her website.

In a real break from her predecessors, Warren also proposes an end to ambassadorships for political donors.

“The practice of auctioning off American diplomacy to the highest bidder must end,” she wrote.

While Warren does not specify whether her proposal to decouple donations and ambassadorships would result in an executive order, new legislation or simply a campaign pledge, she has vowed to “put America’s national interests ahead of campaign donations and end the corrupt practice of selling cushy diplomatic posts to wealthy donors — and I call on everyone running for president to do the same. I won’t give ambassadorial posts to wealthy donors or bundlers — period.”

Warren’s plan didn’t get a lot of attention at the time she announced it, but the Ukraine scandal might give it some traction with voters — although “reforming the foreign service” is unlikely ever to rise to the top of any voter’s list of priorities. Increasing funding for the State Department is, of course, the purview of Congress.

But her pledge about appointments is one she can keep: A president can nominate whoever she chooses for ambassadorships, although they are subject to confirmation by the Senate. And the proposal, whatever its fate, reinforces the image she has cultivated of being independent and incorruptible, funding her campaign on donations averaging around $26.

Whoever a President Warren appoints as ambassador to the Court of St. James (the formal designation for the embassy in London) may in fact be a donor to her campaign. But not a million-dollar donor.

Cover thumbnail photo: Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Gordon Sondland, U.S. ambassador to the European Union. (Photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: AP [2], Getty Images, AP)

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News:

Greta Thunberg: Powerful men 'want to silence' young climate activists

'I've never had a crystal': Marianne Williamson demands to be taken seriously

Trump tweeted ‘billions of dollars’ would be saved on military contracts. Th

Before a notorious phone call, the Trump administration was lauded for helping Ukraine

PHOTOS: New book unveils unique insights from behind the lens of conflict photography