Unfiltered: Men 'think it's a weakness to say that you have a weakness'

It’s 1993, and pioneering hip-hop group Run-DMC is on tour to promote its new album, “Down With the King.” Jam Master Jay is scratching something mean at the turntables, and Rev. Run and DMC are dominating the stage — Adidas stomping, mic clutching, beats thumping. Donning their trademark leather jackets with black Kangol hats and fat gold chains, the group members are riding a wave of success they hadn’t experienced since the mid-’80s.

…D’s for doing it all of the time,

M’s for the rhymes that are all mine,

the C’s for cool — cool as can be.

(Why you wear those glasses?) So I can see.

But when the gig wrapped and the members returned to their hotel rooms for the night, all Darryl “DMC” McDaniels wanted was to die.

“It was just this big void in me. And that void was just so uncomfortable. That feeling of something’s missing, something’s wrong, just became so uncomfortable that I didn’t want to live no more.”

At 29, Darryl was at the top of his game as a bona fide emcee and hip-hop icon. But a dangerous mix of alcohol addiction, health problems and severe depression, followed by the deaths of people close to him and a shocking family secret, left him in chaos. “I didn’t know what to do for these emotions,” he says.

When a young McDaniels first jotted down his rhymes, he never dreamed of being in show business. For him, hip-hop was a way to tell stories and explore worlds unknown: “I was just making up these comic-book-type superheroes — Devastating Mic Controller, King of Rock — rhyming stories for me.” A geeky kid by his own admission, McDaniels read, collected and drew comic books. “My whole confidence and strength in life,” he explains, “was me pretending that I was like the Hulk, like I was like Peter Parker and Spider-Man, that I was courageous like Captain America.”

One day, when he was in ninth grade, his friend Joseph Simmons stopped by his home. He took a look at McDaniels’s rhymes and, impressed with what he saw, said, “Yo! Whenever my brother Russell lets me make a record, I’m putting you in my group.”

McDaniels, however, was not so eager.

“I never wanted the world to hear those things,” he recounts. “That was for me and my pleasure in my room alone after I did my homework.”

Four years later Simmons brought McDaniels into the studio, where they made their first record, featuring “It’s Like That” and “Sucker MC’s.” In 1979, the group Run-DMC was born, consisting of Jason “Jam Master Jay” Mizell, Joseph “DJ Run” Simmons and Darryl “DMC” McDaniels. Their rise to stardom was meteoric; they became the first rap and hip-hop group to receive gold and platinum certifications, get nominated for a Grammy Award, have their music videos broadcast on MTV, and be featured on the cover of Rolling Stone. At the time, no other hip-hop artists had achieved that level of mainstream recognition. With the group’s newfound success, however, came a lot of pressure for McDaniels, who felt nervous when it was time to hit the stage. He recalls, “I didn’t think at the time that my imagination alone [was] enough to have me take on anything that [came] my way. So I went for some assistance.” He found his strength in a bottle of Jim Beam – “up onstage in front of people, alcohol became my superpower” – and that spiraled into an addiction that culminated in guzzling as many as 12 40-ounce bottles of Olde English malt liquor a day.

One morning, McDaniels woke up with excruciating pain: A visit to the emergency room revealed that he had acute pancreatitis. The doctors warned, “You have two choices: You can drink and die, or you can not drink and live.” It was the wake-up call he needed, and one that he did heed, but McDaniels was worried about his next performance because he had always been drunk when onstage. It was “scary,” he recalls. “Can I still be the Devastating Mic Controller, King of Rock, and stand next to Jam Master Jay and DJ Run? How’s that going to be?” He discovered that performing alcohol-free was miles better than when he was intoxicated. “When I finally got sober, I saw the world in a way that I never, ever saw it. And it was so, so way more magnificent.”

In 1988, Run-DMC took a two-year hiatus. In such a young, budding music scene as rap and hip-hop were at the time, two years seemed like a decade: The genre had morphed and evolved, with new artists and new sounds on the scene and the charts. Run-DMC’s popularity was waning, and it didn’t help that their most recent album, “Back From Hell,” received little to no praise. That all changed in 1993, when the group teamed up with renowned hip-hop producer Pete Rock to release the album “Down With the King.” The titular single became a huge hit, leading to tours with Limp Bizkit, Naughty by Nature, and much later, Aerosmith, effectively revitalizing their career. “Here we are, back on the road. Here we are, back on the charts. Here we are, back on MTV and every video platform,” says McDaniels, “And I remember getting offstage one day and going back to my hotel room, lying in bed [thinking], ‘I don’t want to live no more. I want to die. I don’t like this feeling. What am I feeling?’ … This dread of existence came over me, and I didn’t know what it was.”

What McDaniels did not know at the time was that he was suffering from severe depression. At one point, he decided he would commit suicide – but only after releasing a memoir: “If I die tomorrow, if I do kill myself, I want people to know what was up with Darryl,” he reasoned. It was during his research into the details of his birth that he received a phone call from his parents with unexpected news: he had been adopted. “When I heard that,” he recalls, “it was like, ‘I’m really going to kill myself now ’cause now I’m not even my mother’s and father’s.’ It was hurtful; it was just crazy… Wrecked my whole life.”

McDaniels felt lost. “I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know that you could go seek help. I didn’t know that there [were] people, and organizations, and doctors, and therapists and programs that could help you.” Once again, he sought solace in alcohol. “I went right back to the thing that I thought would give me the strength to get through all that, and Jack Daniels and Jim Beam became my best friends.”

Then, more than halfway through the tour with Aerosmith, McDaniels inexplicably lost his voice. Doctors were dumbfounded. “They all look at me and go, ‘We don’t know how to tell you this, son, but there’s nothing physically wrong with your voice.’” As the tour continued, McDaniels’s drinking intensified. Shortly thereafter, on Oct. 30, 2002, Jam Master Jay was gunned down in his Queens recording studio. His slaying is still unsolved. Looking back, McDaniels says, “I didn’t know what to do for these emotions, so now I’m self-medicating, drinking the alcohol that I’m not supposed to drink, ’cause it’s going to kill me … there’s a lot going on inside of me.” Soon after, McDaniels’s adoptive father passed away. “My whole world got snatched out from in front of me,” McDaniels admits.

At this point, the drinking had reached an all-time high: After multiple pleas from his family and friends, McDaniels checked himself into rehab in 2004. During an emotional first therapy session, he was able to open up and confide his troubles with addiction, adoption, and thoughts of death — something he never thought would be possible. McDaniels credits this crucial moment of vulnerability with saving his life: “If you don’t reveal how you really feel, you will never heal,” he says. “Being honest with yourself is a beautiful thing. … Dealing with my truth, man, it’s the most powerful thing that anyone could do.”

He adds: “[There’s] this thing with men where it’s weak to say that you have a weakness … but it’s the strongest thing that you could ever do in your life, because [in] admitting that you have a weakness, your strength is revealed to you.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control’s National Health Interview Survey, each year more than 6 million men suffer from depression – and only one in four has talked to a mental health professional about it. Additionally, men are four times more likely than women to commit suicide.

The key is to experience your feelings, McDaniels says. “If we remove the guilt and shame, we remove the pain: There’s nothing wrong with going through what you’re going through.”

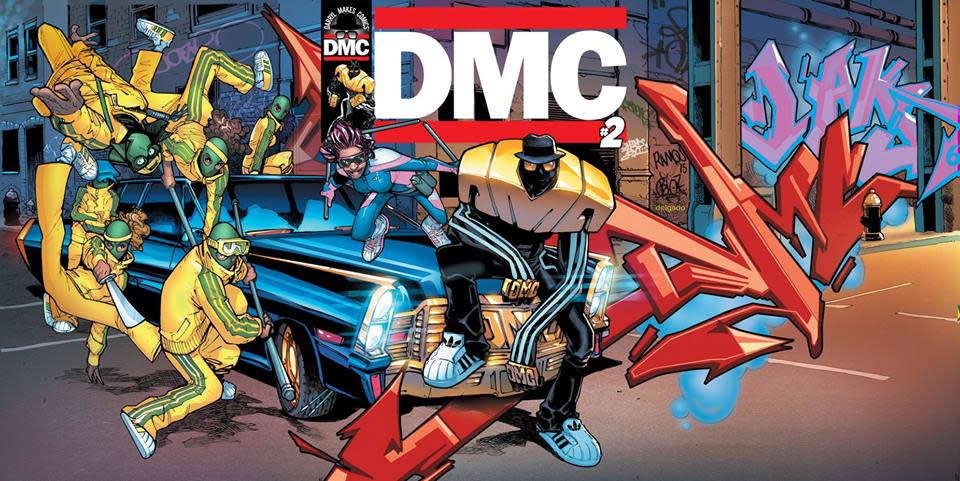

Two years after rehab, McDaniels co-founded the Felix Organization to help foster children develop self-esteem and confidence. He also wrote a book, which was published in 2016, titled “Ten Ways Not to Commit Suicide”; released a new vinyl called “Back From the Dead – The Legend Lives”; and opened his own comic publishing house, Darryl Makes Comics.

“What happened to me was, I realized, with the same sincerity and honesty that [I say] I’m the greatest thing on the earth [that] I have an even more greater power by letting you all know I’m not doing good, I failed, I fell off, I’m down too. [That] has a greater effect than me bragging about how everything is all right.”

McDaniels takes a second to think back to that little kid growing up in Hollis, Queens, before all the pressure, the show business, the awards, and accolades: “No matter what any of you all are going through, you all have a power and a reason … a reason to be alive. It’s not to be with your family. It’s not to be the CEO. It’s not to be rich and famous: You have to stay alive because you and your story can save somebody’s life.”