Ed Gillespie's scaremongering TV ads may define his campaign

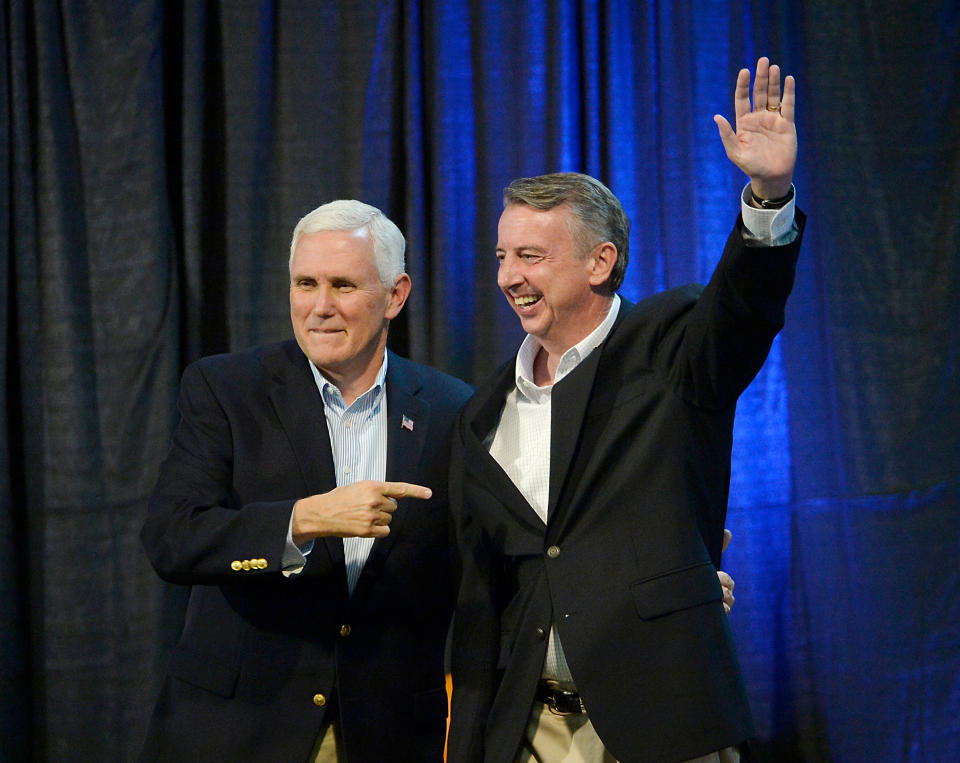

Ed Gillespie often insists that the gubernatorial election in Virginia should mainly be a dialogue about the deeply researched policy papers he’s put out on seemingly every topic under the sun.

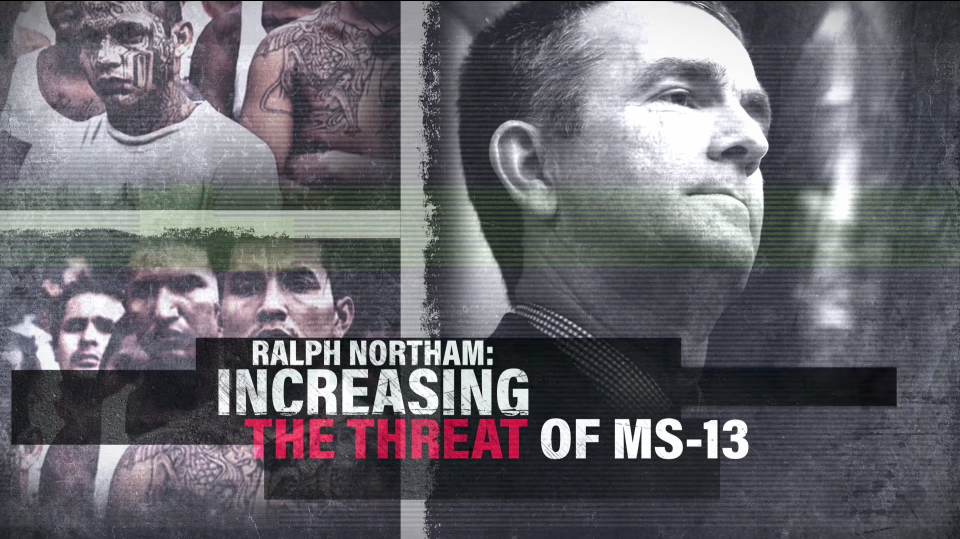

And while that may be true, the Republican’s campaign might be best known at this point for a series of TV ads in which photos of heavily tattooed Latino men are displayed as the words “KILL, RAPE, CONTROL” flash across the screen.

“That ad has aired, to my knowledge, far more than any other ad,” said political sage Larry Sabato, director of the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics. “I see it several times a day in flipping through channels.”

The ad stretches facts to suggest Democratic nominee Ralph Northam — the incumbent lieutenant governor — authorized sanctuary cities in Virginia for undocumented immigrants, even though there are no sanctuary cities in the commonwealth. But it is most noteworthy because of how different it is from the way Gillespie has talked about the Latino community in the past.

Gillespie supporters like Jason Miyares, a Republican state delegate from Virginia Beach and a former prosecutor, say that the GOP nominee for governor is running an inclusive campaign and that his ad is simply endorses “law and order.”

“I give Virginians a lot more credit maybe than some other people,” said Miyares, the son of a Cuban refugee. “They understand the average MS-13 member is not the person they live along side with, work alongside with, and worship alongside with. Virginians are a lot smarter than that.”

But it’s hard to imagine Gillespie running an ad like his MS-13 spot a few years ago, because for over a decade he’s been a leader of the Republican effort to bring Latinos into the GOP and tone down anti-immigration rhetoric. The inflammatory nature of the TV ad illustrates to many observers how even the most moderate Republicans are being pulled to the hard right by the Republican Party base.

And there are echoes of another devoutly religious political figure who decades ago ran statewide in a Southern state with a moderate message, lost, and then changed his approach in a second campaign to try to win over voters animated at least in part by fear or dislike of minorities: Jimmy Carter.

*****

In 2010, Gillespie oversaw the GOP’s effort to take control of more state legislatures. It was a wildly successful effort that gave the party control of redrawing congressional districts in many states, an advantage Gillespie helped the party use to augment their control of the House.

For Gillespie, it was another victory in a career marked by success, from wealthy and powerful lobbyist to chairman of the Republican National Committee to top White House adviser under President George W. Bush.

But Gillespie was still troubled by the Republican Party’s movement away from being a welcoming place for racial minorities, especially Latino voters.

In the summer of 2011, Gillespie announced that he wanted to recruit 100 Latino candidates to run as Republicans for state legislature seats around the country. “The demographics of America are changing, and any political party that fails to recognize that is going to find themselves consigned to minority status in the not-too-distant future,” Gillespie said.

A month later, I interviewed Gillespie in his Virginia office just across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., to talk more broadly about the Republican Party and the Latino vote.

“As Latinos become more integrated into our society and our country, they’re going to register in bigger numbers and more actively participate in the political process,” Gillespie said.

Gillespie said the GOP had alienated Latino voters through its harsh anti-immigration rhetoric.

“Sometimes [the GOP] sounded anti-immigrant,” Gillespie said. “And that turns people off.”

Part of the solution, he said, would be more aggressive outreach to the Latino community.

“We need to be on Telemundo and Univision and all of the Spanish-language radio markets in some of the urban areas and get our message out,” Gillespie said.

In 2013, Gillespie was a supporter of the comprehensive immigration reform effort, which passed the Senate but ran out of steam in the House.

A year later, when Gillespie ran for the U.S. Senate, he was less enthusiastic about the 2013 reform effort. But in 2015, he reiterated his past comments about the changing face of the electorate, and said the GOP “must adapt.”

But then in 2016, Donald Trump was elected president while denouncing Mexican immigrants as rapists and criminals, and Gillespie’s path to the governor’s mansion became far more complicated. Things became even more difficult when Gillespie only barely defeated a Trump-like primary challenger in June, Corey Stewart.

“[Gillespie] almost lost the primary to a far-right guy who was campaigning as a borderline racist,” Sabato said. “I mean [Stewart’s] from Minnesota, good God. I’ve known him for years. He’d say anything to get in office.”

Gillespie’s narrow win was a wake-up call. A large number of Republican voters were obviously attracted to Stewart’s hard-line anti-immigration stance and to his robust defense of Confederate monuments.

Gillespie and his campaign will often talk about his detailed policy positions on a wide range of issues, from “sea level rise” to transportation to substance abuse and addition to criminal justice reform. Gillespie has released 20 policy papers explaining how he would govern, and his favorite lament is that the press is not covering issues of substance.

That may be true, but Sabato said that’s because the voters Gillespie needs to win aren’t motivated by those issues either.

“Gillespie has had more detailed policy positions than any candidate I’ve seen,” Sabato said. But Trump-style voters “don’t care about any of that.”

The Trump people have no enthusiasm for [Gillespie] but the only thing they’ve praised him for is his anti-immigrant and pro-monument stances,” Sabato said.

The Gillespie campaign believes this is a misreading of the issues, and that gang violence and monuments are both issues that resonate with wide swaths of Virginia voters.

“This is a serious issue in the commonwealth, and a gubernatorial candidate should absolutely be talking about it and putting forward solutions to address it and make our communities safer,” said Gillespie spokesman Dave Abrams. “The ads highlight important policy differences between Ed and Ralph Northam. Ed is the only candidate in the race with a detailed plan to combat MS-13 and other gangs to make all Virginians safer, especially those who live in immigrant communities that are the most vulnerable to MS-13 violence.

“The lieutenant governor’s campaign is conflating violent criminals here illegally with all immigrants, not Ed, who is himself the son of an immigrant. Ed knows that we can be a welcoming commonwealth, and a safe one too,” Abrams said.

But others believe that Gillespie, a devout Catholic, is doing what’s necessary to win, but may not be excited about it. Several Democrats in the state remarked after Gillespie and Northam’s second debate that even though the monuments controversy was hurting the Democrat, who had endorsed removing many of them from public places, Gillespie didn’t take the opportunity to press the issue.

“He pulled his punches,” one senior Democratic operative told me, arguing that it showed Gillespie had moral qualms about being a cheerleader for Confederate statues.

Gillespie said in the debate that “clearly, when you’re on the side of slavery, you’re on the wrong side of history.” He also advocated “putting the statues in historical context,” which often means moving them out of public places of honor to museums, though Gillespie himself has never advocated for that, and Northam has.

And when I interviewed Gillespie this past summer back in his Alexandria office, he had positive things to say about the Black Lives Matter movement.

But Gillespie’s TV ads about monuments leave a different impression, repeatedly hammering the point that he believes they should “stay up.”

“Our history is our history, and we need to teach it, not erase it,” he says in one. “They need to stay up.”

Sabato said Gillespie’s MS-13 ad, and his ads in favor of Confederate monuments, were clearly not in line with who Gillespie is. But, Sabato said, “given a choice between staying pure and possibly winning, he’s chosen possibly winning, which is what most politicians do.”

It is reminiscent of Jimmy Carter’s 1970 run for governor of Georgia.

*****

In 1966, Carter, a state senator, made winning black voters a focus of his campaign for governor. He lost, and watched Georgians instead elect an avowed segregationist, Lester Maddox.

Two years later, Alabama Gov. George Wallace — a voice for racist whites who wanted to preserve segregation — won five Southern states and 10 million votes in his third-party run for president. One out of every five Americans who voted in that election cast a ballot for Wallace.

In 1970, Carter ran again for governor in Georgia, and that time he won. But his campaign had a very different flavor that time. “Carter has pitched much of his campaign toward Wallace voters,” the Atlanta Journal-Constitution wrote on September 6, 1970.

Carter’s TV commercials included a catch phrase referring to Carter — “our kind of man” — that was cribbed from Wallace’s own ads in Alabama. Carter himself criticized his opponent, former Gov. Carl Sanders, for blocking Wallace from speaking on state property, and told voters he’d gladly have Wallace address the legislature.

Carter’s aides were responsible, according to his longtime adviser Peter Bourne, for distributing flyers showing Sanders standing next to an African-American player for the Atlanta Hawks, where Sanders was part owner, while the player poured champagne over Sanders’ head.

Carter promised white parents who had pulled their children out of integrated schools and put them in all-white private schools that he would do everything he could for private schools. And he sought and received the support of the state’s most strident white supremacists and segregationists, including Maddox.

Carter defended himself when I interviewed him in 2015 for my book on the 1980 primary.

“I never made a racist statement or a racist inclination,” Carter told me. “But I did get the more conservative country votes there in Georgia because I never did anything to alienate them.”

But according to published reports at the time in 1970, Carter’s response to his win was muted, because the born-again Christian questioned the lengths to which he’d gone to achieve his goal.

After he won, Carter declared in his inaugural speech that “the time for racial discrimination is over” and tried to reassure black leaders in the state that he would be for them as governor. Carter went on to become president in 1976, and his post-presidency has been a model of philanthropy and humanitarian work.

For Carter, that 1970 campaign is an obscure footnote. If Gillespie defeats Northam on on Nov. 7, perhaps decades later his current campaign will also be largely forgotten. And the race is tight by all appearances.

But like Carter, Gillespie will likely have to grapple with his own conscience regardless of the election outcome.

In 2014, Sanders said in an interview that while he was disappointed that his political career ended in 1970, he was happy with the decision he made not to make a play for Wallace voters.

“Everyone I know of at some point in their life takes a stand in what they have done. What I did, what I didn’t do, I’m happy and satisfied,” he said.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: